This article originally appeared in the November/December 2010 edition of the Museum magazine.

Straddle a Harley-Davidson after touring a century of motorcycle history. Hop into the “bunny suit” Intel technicians wear to craft computer chips, then check out a shop stocked with logo T-shirts, mugs, and other swag. Hear tales of Coca-Cola’s efforts to combat AIDS in Africa before downing as much soda as your digestive tract can handle.

One part education, one part sales: This is the corporate museum. Often tucked into corners of company offices, this may be the most forgotten-and, perhaps, the least welcome-member of the museum family. But these black sheep are being increasingly embraced by the public. They’re also exploring new ways of reaching and engaging their visitors, which may interest their more conventional counterparts.

Corporate museums are often overlooked as a group within the field. As Victor J. Danilov observes in his book A Planning Guide for Corporate Museums, Galleries, and Visitor Centers, these institutions “are often not listed in museum directories or elsewhere.” The museum may serve as the corporation’s nonprofit arm. Still, Danilov notes, because corporate museums are “part of corporate organizations and frequently commercial in nature and purpose, they generally do not receive the visibility, publicity, and recognition afforded community-based nonprofit museums.”

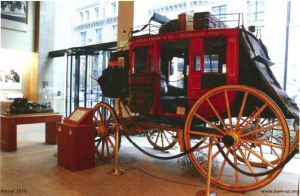

So what do traditional museums share with these renegades? Corporate museums have permanent collections, with holdings ranging from 19th-century stagecoaches to glass Coke bottles to Pentium processors. Artifacts are collected, conserved and interpreted with the goal of preserving history and with the best possible care. “We honestly try to follow what we consider to be typical standards set by other history museums,” says Beth Lindquist, director of the Union Pacific Railroad Museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa. “We don’t feel we should stray from that.”

Many corporate museums organize special exhibitions, such as the Harley-Davidson Museum’s recent presentation of “True Evel: The Amazing Story of Evel Knievel.” They have teams that discuss which objects to display, design the installations and develop interpretive materials.

But they don’t have to go to auctions or wait for donations: Corporate museum collections are generally provided, even produced, in-house. And unlike, say, a museum of technology, these institutions generally don’t use their objects to provide an overview of an industry, but instead, emphasize one company’s contribution to that industry-sometimes excluding any mention of others.

In addition, none of it may be for the public’s benefit. As Danilov writes, corporate museums are typically “commercial instead of nonprofit, perhaps looking to educate but more so looking to promote a brand. They may not have a professional staff, or welcome in audiences besides clients, VIPs or personal pals of the CEO.”

When they do welcome the public, the public seems to come. Hundreds of thousands have entered the Harley-Davidson Museum’s doors since it opened in Milwaukee in 2008. More than 136,000 visitors checked out Intel Corp.’s museum in Santa Clara, Calif., last year. And up to 1,000 people stream daily through the San Diego branch of Wells Fargo’s suite of nine museums.

Why do people go? In July 2010, user David B. posted his reasoning on Yelp, the consumer review website. His father, a “gadget guru and electronic geek,” had apparently been craving a trip to one of the technology museums in Silicon Valley. The pair wound up at the Intel Museum in the company’s headquarters. “Yes, it is a giant advertisement for Intel. Yes, it does get annoying,” David commented on his museum experience. “Still, I was amazed to learn of the role Intel played in the refinement and growth of microchip technology.”

Beyond wowing us mentally, corporate museums appeal to our hearts. “I think it’s because they tell a story, usually the American story,” offers Andrea Casey, associate professor of human and organizational learning at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. “Hershey, Coca-Cola-they tell the story of someone who had an idea and not only created a company but created a legacy.”

Plus, it gets personal. “The other piece of it is that they resonate with your story,” Casey adds. The New World of Coca-Cola in Atlanta leads visitors through the decades with more than 1,000 artifacts. Highlights of its “Milestones of Refreshment” galleries include an original 1880s soda fountain fashioned from marble and onyx and a soda can that traveled into space-making Coca-Cola the first sparkling beverage to do so more than a century later. Somewhere in the company’s timeline, the visitor’s story begins. “You say, ‘Oh yeah, I remember that,’ or, ‘I remember my parents talking about that,”‘ Casey explains. “You’re seeing your life reflected in the museum.”

The personal touch is easier to come by at corporate museums than traditional ones, she adds. At a natural history museum, for example, “even though they’re telling a story of mammals or stones or gems, it’s not a real story that connects as much with you and your life story.”

The New World of Coca-Cola has taken special care to emphasize its main product’s connection to visitors. The “Pop Culture” gallery features an installation titled “My Coke Story,” an opportunity to read Coke-related memories other guests have shared and then contribute your own. “It’s really about making connections with our consumers, our guests, with a product that’s been a major part of their lives,” says Chris Wallace, director of operations.

Wallace’s easy interchange of “guests” and “consumers” isn’t common practice in most museums.

In 2007, the New World of Coca-Cola moved into a $96 million building in Atlanta, less than a mile from corporate headquarters. While Wallace says the institution features museum elements and “falls into the category of a museum,” he also classifies it as a “corporate attraction” as it incorporates theater elements that don’t focus on educational or historical content. Take, for example, the Secret Formula 4D Theater. It screens a film that follows a scientist’s quest to reveal Coca-Cola’s secret of success, enhanced by moving seats and other special effects.

It rings of Disney World or Busch Gardens-but also of some recent additions to the “traditional museum” clan. In 2008, the Newseum moved into a $450 million building in Washington, D.C. It features a slew of cutting-edge attractions, most branded with corporate names. For instance, the Walter and Leonore Annenberg Theater screens “I-Witness,” a four-dimensional “time travel adventure” that highlights key moments in journalism history while spraying water and shooting virtual bullets at its bespectacled audience. The film is promoted on the Newseum’s website as combining “museum-quality content with theme-park excitement.”

Where the New World of Coca-Cola has the “Taste It!” lounge, offering samples of 70 beverages arranged by continent, the Newseum has “Today’s Front Pages” of 80 newspapers from around the world. Coca-Cola has “Bottleworks,” a functioning bottling facility; the Newseum has the Knight Studio, which networks use to produce such programs as “This Week with Christiane Amanpour” and “Good Morning America.”

But while the New World of Coca-Cola is peppered with one corporate logo, the Newseum has different company names attached to nearly all of its 14 main exhibition spaces: the Cox Enterprises First Amendment Gallery, the Time Warner World News Gallery and the Bloomberg Internet, TV and Radio Gallery, to name a few. And though the Newseum may represent aspects of these companies, it’s not providing a total picture. As Casey puts it, “There’s a difference between sponsoring something and having it part of who you are.”

Corporate museums could also be compared to venues like the Hard Rock Cafe or ESPN Zone. These are both well known, well-branded corporations and their restaurants are full of memorabilia that relay key stories in American history. “But it’s not telling the company story,” Casey clarifies. “They’re linking with culture-American music culture, American sports culture- and people can see themselves in some of the exhibits, but there’s not a storyline. They’re not interactive. You just see stuff at Hard Rock and eat your burger and then move on.”

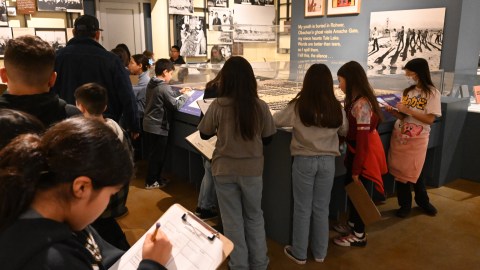

As in many museums these days, interactives are key. Housed in an old Carnegie library, the Union Pacific Railroad Museum entertains visitors-around 25,000 annually- with such displays as an interactive map table, which highlights towns that sprouted along the railroad’s route during its westward expansion. Other attractions have earned a devoted following: “We have one young man, 3 or 4, maybe 5, who has to come in to ride our train simulator about once a month,” Lindquist says.

The Union Pacific Railroad Museum was among the first corporate museums in the nation. It was originally established in Omaha, Nebr., in 1921 after several pieces of silverware from Abraham Lincoln’s personal train car were found in a company vault. The railroad’s then-president, Carl Gray, decided that Union Pacific’s history

needed to be preserved for the American public. “He started collecting from employees, retirees,” says Lindquist. “We’ve been doing that for 100 some years now.” Today, the museum houses one of the oldest corporate collections in the nation, dating to the mid-1800s and tracing the development of the railroad and the American West.

Wells Fargo opened the first of its museums in San Francisco in the 1930s on the site where the bank first opened for business in 1852. The company had been exhibiting its history in some respect since it put its trademark stagecoach and other artifacts on display at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

It wasn’t until the second half of the 19th century that corporate museums experienced their greatest growth, according to Casey’s paper “Viewing Corporate Museums Through the Paradigmatic Lens of Organizational Memory,” co-written with Nick Nissley of the University of St. Thomas. There was a spurt of renovated and newly opened corporate museums throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The trend continued through the 1990s, including the opening of Motorola’s Museum of Electronics and Binney and Smith’s Crayola Hall of Fame, and into the 2000s. Today, there are museums associated with a vast range of companies. The Hoover Historical Center dishes dirt on the life of a vacuum entrepreneur; Hershey’s Chocolate World just unwrapped its “Create Your Own Candy Bar” attraction this year.

But the nature of corporate museums has changed drastically through the decades. “The early corporate museums were mostly historical in nature, tracing the history of the company, pointing out the contributions of the founder and other key individuals, and displaying documents, photographs, and products of the past,” Casey and Nissley write. More recently, Danilov notes, the focus has shifted toward public relations and marketing.

Companies’ goals for their museums vary, and the measure for success is unique to each, says Jason Dressel, vice president of business development at the History Factory, a Virginia-based firm that helps businesses strategically use their legacies. Overall, though, he says it’s rare that a company looks to the museum as a source of revenue. More typical goals include employee engagement, increasing the loyalty of a customer base and “being a good partner in the community.”

The latter is emphasized in the New World of Coca-Cola. The “Portrait Wall” shows larger-than-life images of people around the world, complemented by their spoken tributes on how Coca-Cola has touched their lives. Showcased are accounts of the company’s environmental projects in India, HIV/AIDS education programs in Africa and youth soccer initiatives in Mexico. Emphasizing the good the corporation does for others is, in turn, good for the corporation, Wallace says: “Because we’re a corporate museum, we need to be cognizant that we’re attached to a company that’s generating business results, and people making a beverage decision want to know that they’re purchasing a good from a company that’s respectful and does good things in the world.”

In this way, a museum can help a company separate itself from the pack. Wells Fargo has always had competition, such as longtime rival Bank of America. “We feel our history helps differentiate us from them,” says Glen Myers, curator, and manager of the Wells Fargo History Museum in San Francisco. “If you’re looking for a checking account, an ATM, it doesn’t matter what bank you work with; they all offer pretty much the same thing. What’s really valuable to us is how our history, which is part of our brand, makes us stand out from our competitors.”

All nine of Wells Fargo’s museums have free admission and tour programs, with a special focus on complementing schools’ American history curricula. “Every fourth-grade teacher in the Bay Area knows about us because their students have to learn about the Gold Rush,” Myers notes. This also fits with Wells Fargo’s mission to focus on the community. “Even though we’re a really big bank, we’re always community-oriented, so the value for the community is really important. It’s our top priority,” he adds. “The company understands that if the community is healthy, the bank will be healthy.”

Similarly, the Intel Museum invites classes for tours and programs designed around teachers’ lesson plans. They’re hosted in an interactive learning lab where students explore electrical conductivity, sequential problem-solving and the sterilized “clean-rooms” where computer chips are made-concepts that could come in handy if they one day work at Intel. “We hope to inspire schoolchildren, who make up a large percentage of our audience, to have an interest in science and technology and to perhaps pursue a career in technology or engineering,” says Tracey Mazur, museum curator.

By and large, though, most companies see the museum as a platform to promote their brands. The museum must then be the company incarnate, representing the essence, the entirety of the brand more than an individual soda can or leather jacket could do. Dressel stresses “authenticity” as a current corporate-museum buzzword. He recalls a company he worked with a few years ago that wanted a museum with a much less formal design than most clients. “That was their culture-an informal company culture,” he explains. “They’re not the kind of organization that would have mahogany and steel and artifact cases; they wanted primary colors and plastic. If we had produced something for them more in keeping with what other clients want, it would’ve been inauthentic for them.”

One of the History Factory’s biggest challenges is helping corporations sort out which stories they want to tell, Dressel says. Large corporations tend to have a “terrific number of assets and stories they can use that would be appropriate for a museum,” he says. “The challenge, however, is that those assets or stories are [sometimes] completely irrelevant to who the company is today and where they’re going.”

An example is the Norfolk Southern Rail Co., which once was involved with passenger travel but hasn’t been for many decades. {It now mostly hauls coal.) From a business perspective, “there’s not a lot of merit in focusing on those aspects of their history,” Dressel says. In such cases, he generally urges lending or giving away “irrelevant” artifacts. “We may suggest to the company, ‘You have great assets here, but it might make more sense to donate these to a local or trade museum that is going to get more value out of them than you are.”‘

At Norfolk Southern, it meant choosing to dedicate valuable exhibition space to a simulator that allows visitors to try their hand at running a locomotive instead of displaying a former passenger car that represents a trade the company hasn’t been involved with for decades. “Using the space to tell a story that focused more on safety and innovation was more relevant than sharing a passenger car with old china patterns from the 1920s,” Dressel recalls. “It’s not about covering it up. It’s not that they didn’t want to disclose that. It’s more a question of balance.”

Corporations often choose to omit certain artifacts, references or even entire sections of their histories from their museums. For instance, you won’t find mention in the New World of Coca-Cola of the longstanding legend that Coke used to contain traces of cocaine. Also not included in the wall text: a certain rival that shall not be named (but whose name starts with P and rhymes with “mepsi”). Wallace insists the institution-which staff also refers to as “the Happiness Factory”-simply prefers to focus on the positive. “We never really refer to our competitors at all,” he says. “We try to celebrate the positive aspects of our company and brand.”

But if the competitor is part of the story (think cola wars), shouldn’t the corporate museum share that with visitors? “I don’t think it’s an ethical responsibility to put everything on the table in corporate museums,” Casey asserts. “First of all, you couldn’t. We all have to select parts of our history that we remember, and then select the parts we do remember and choose not to tell other people about. There’s simply too much to tell in the history of a company or of a person.”

Harley-Davidson takes a different tack. It sees baring all-including, and perhaps especially, the dirty underbelly-as reinforcing its gritty, rough-and-tumble brand. Bill Davidson is the new vice president of the museum as well as the great-grandson of Harley-Davidson co-founder William A. Davidson. The younger Davidson refers to the company’s my-year-long history as “a kind of Cinderella story, with a lot of ups but also some downs. That rich culture and those experiences are very intriguing to our loyal customers as well as to people who are not close to the brand.”

The museum includes displays on Harley-Davidson’s struggles with economic downturns and competition from both domestic and overseas manufacturers. It also doesn’t shy away from discussing missteps, such as its 1969 merger with the American Machine and Foundry Co. The resulting lower-quality products led to a drastic drop in sales and some uncomplimentary new nicknames, including Hardly Drivable and Hardly Ableson.

Davidson acknowledges that the museum could have opted to gloss over these issues, but he says there are benefits to getting real, both internally and externally. “We are true believers in understanding our successes as well as our failures,” he says. “The failures that we have had have provided greater expertise and direction moving forward as to what not to do, and this is very evident as you walk through the museum. Our brand is very genuine.”

As corporations tackle their pasts, they’re considering their futures, and it’s again changing how these museums function. In the same way that traditional museums are trying to adapt to an increasingly global culture-by emphasizing their virtual presence or establishing satellites in Europe and Asia corporate museums are expanding their reach. “As companies have become less centralized and more global and are moving away from the model where they have a high concentration of employees in one place, the whole concept of a museum for us and our clients has changed,” reports Dressel. “We’re now working with companies that are creating museum-quality experiences in lots of different spaces throughout their enterprises.”

CME Group in Chicago is one such company that is going global with its corporate-museum concept. As a leading financial exchange, it welcomes guests ranging from American government officials to international dignitaries and prime ministers. “There are a ton of people who come through here and want to understand our market, our company. Futures were frankly invented here,” says Anita Liskey, managing director of corporate marketing and communications. The company is currently establishing a series of exhibition spaces. CME Group has had “museum-like places” before, says Liskey, but this new setup will provide a more comprehensive history covering the full evolution of markets and global commerce.

It will also be much more spread out. The story will be told in pieces-in visitor centers, public lobbies, meeting spaces and conference rooms, in corporate headquarters and subsites worldwide. “Our goal was to make our story an active part of our institution, even for employees. Walking through the halls, they’ll pick up bits of information,” Liskey explains. “Some people will take a deep dive; other people will get an at-a-glance story as they walk through.”

Circling back to the concept of authenticity, companies today are telling their stories “where it’s relevant to the kind of work that goes on there,” Dressel says. “It’s a more purpose-driven kind of storytelling versus creating a space and saying, ‘Go downstairs and walk through the museum.”‘ He adds that this is inciting a move away from established museum practices. “While there’s an increasing demand for three-dimensional storytelling, I’m not sure there’s an increasing demand for creating what people have traditionally thought of as a museum.”

At the same time, a sense of stability, of place, is especially desirable for today’s businesses. During these complex, global and economically uncertain times, having a museum may be key for corporations that are struggling to define or redefine themselves- or simply survive. A museum reinforces their identity, says Casey. “It’s very helpful to organizations in terms of strategy,” she says. “It’s knowing where you fit into the world, who you are and where you’re going.”