As I wrote last week one of CFM’s foci in 2011 and 2012 (and probably beyond) will be the future of education. You’ve told us in workshops, correspondence and in feedback to this blog that the trends shaping American education will have a profound effect on the museum field and museums, in turn, can have a profound effect on education. So, here starts our expedition to explore potential futures in the educational realm, mapping the boundaries of the Cone of Plausibility.

We’re undertaking this journey because museums are, first and foremost, educational institutions. The national standards for U.S. museums require that a museum “assert its public service role and place education at the center of that role.” Despite this mandate, and the extensive resources museums dedicate to education through exhibits and programming, the field has traditionally been relegated to a minor role in the educational landscape. Ghettoized as “informal learning,” the vital, experiential, multi-modal educational opportunities afforded by museums are too often regarded as expendable accessories. As the formal K-12 education system is paring back, narrowing focus and marginalizing or jettisoning content regarding arts, culture, history and experimental science, there is more need, yet less funding, for museums to play even this supplementary role. But America is on the cusp of transformational change in the educational system. The current structure has been destabilized by rising dissatisfaction with the formal educational system, the proliferation of non-traditional forms of primary education and funding crises at state and local levels. At the same time, new horizons are being opened by technological advances in communications, content sharing and cultural expectations regarding access, authority and personalization. We are at the beginning of a new era, characterized by new learning economies based on diverse methods of sharing and using educational resources.

What early signals herald the destabilization of the current era, and the possible nature of the next era?

1) The rapid increase in non-traditional forms of primary education.

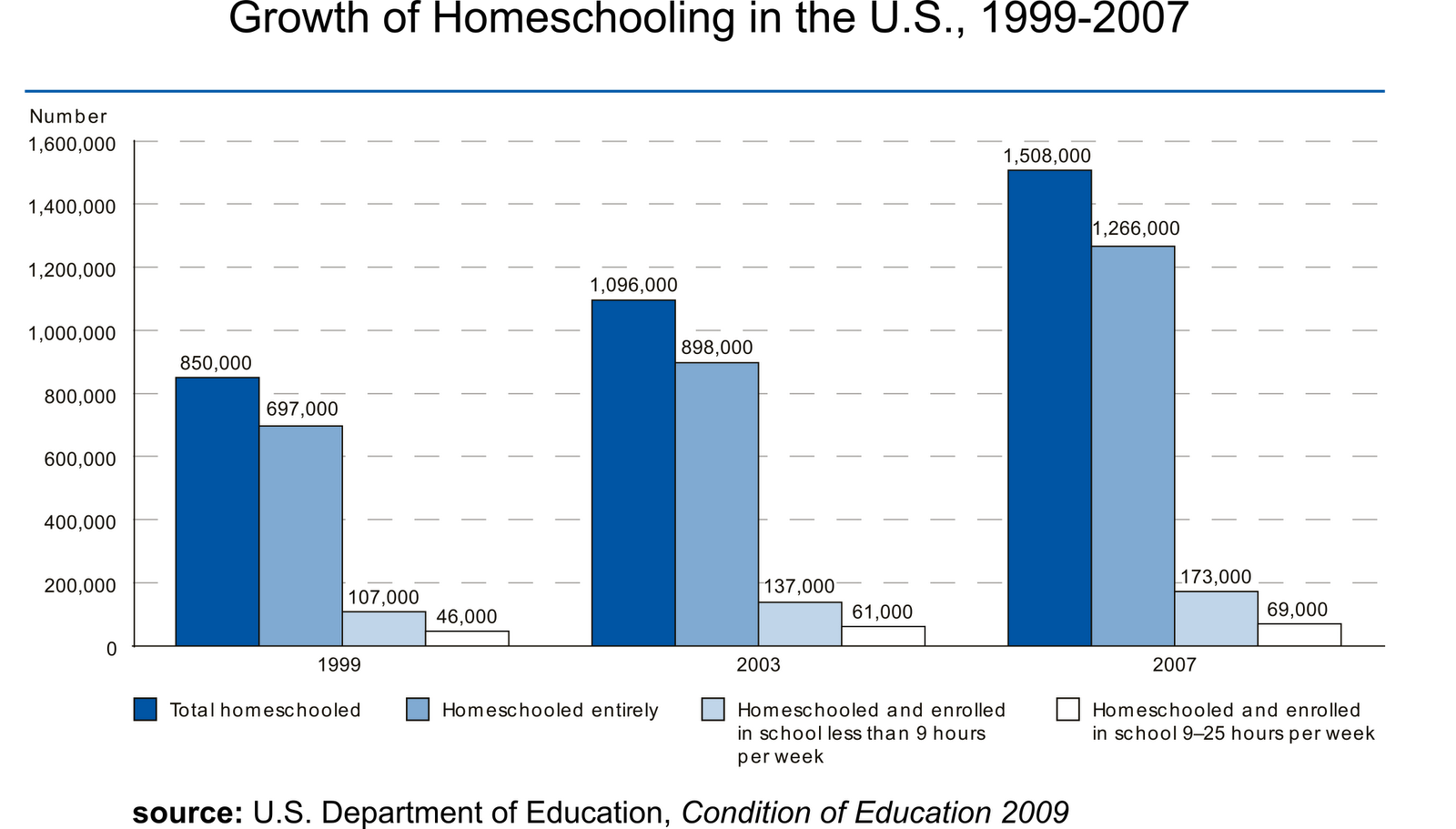

- Homeschooling (77% growth from 1999 to 2007)

- Charter schools (in the same period, the number of students enrolled in charter schools more than tripled, to 1.3 million)

- Online courses (in 2007-08, ~1,030,000 K-12 students took online courses. In 2009, 27 states had statewide virtual schools with a total of 175,000 full-time students.)

2) Rising dissatisfaction with the existing formal primary education system

- Only 31% of American adults say they are satisfied with the nation’s public schools; 69% are unsatisfied—and a third are very unsatisfied.

3) Funding crises for schools at the state and local level

- Radical cuts to education budgets across the country—in New York State, California and elsewhere.

In the coming months, with the help of some fascinating guest bloggers, I’ll be exploring where these trends may lead us. Meanwhile, if you want to start adding information on educational resources to your scanning, I recommend adding the following to your blogroll:

- Innovative Educator

- KW World of Learning

- And the Edutopia collection of blogs

And to fuel your imagination about the future of education, I recommend KnowledgeWorks Foundation’s 2020 Forecast: Creating the Future of Learning.

Okay, I have to admit, I'm interested. But what about practical applications? Places to start? Partnering with schools? Homeschooling systems? Creating curricula that could be considered rather than an extension activity to school-based academics, an actual part of "school" learning? How is this funded? Certainly not from the public educaction system? What about credentialing or standards for education, would museums and museum educators and curators have to meet additional requirements in a different (albeit related field?)? (So many questions…)

All great questions, Day! I hope to explore these in future posts. My early thoughts on how museums can get started:

• Establish connections with educational reformers and alternative schools in their communities, experiment with services that serve the needs of these educational pioneers.

• Pursue multiple options. For example, rather than focusing all educational efforts on meshing with local educational curriculums, museums can look for areas where the school system is not providing instruction, and fill empty niches.

• Be part of the dialog. Get involved in the debate on curriculum, testing and teacher evaluation, and bring the experience of museum staff to bear.

Richard Rothstein, author of Class and Schools: Using Social, Economic and Educational Reform to Close the Black-White Achievement Gap, points out that after-school and summer programs are the norm for upper and middle class families that provide their children with these opportunities as part of their upbringing. Students who do not have exposure to activities, such as the art, music,culture,outdoor education and sports provided by after school and summer programs are less likely to be able to identify with the literary and historical characters they learn about in the classroom. Lack of exposure to activities outside school, will limit personality development along with life skills needed for success.

Museums and other informal learning organizations can play a key role in the transformation of public education. As documented in the NRC report Learning Science in Informal Environments, they bring particular expertise in motivating interest and in identity formation, in addition to the more traditional aspects of learning. These strengths, along with the growing body of knowledge from the learning sciences and technologies that make learning possible any time and any place, have the potential to reshape the educational landscape. NSF has a new program, Transforming STEM Learning (TSL), to encourage innovative projects in this area. The deadline for the planning phase is March 11. See the solicitation for further info: .