This week’s guest post is by Laurie Ossman, director of Woodlawn, a property of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. As I pointed out in an earlier profile of an historic house, museums can use food to build community and tackle serious societal issues. As Laurie points out, such efforts might just be the salvation of historic houses, too.

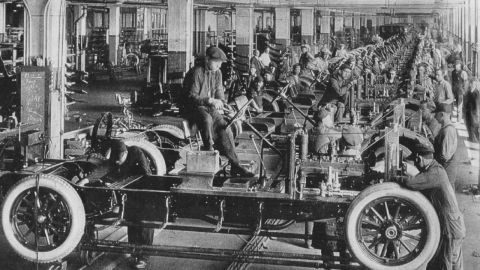

Woodlawn came to the National Trust in 1952 as its flagship site, the very first property of the fledgling preservation organization. In the 59 years since then, the vicissitudes of Woodlawn’s fame and fortunes have served as a barometer of issues and challenges in the microclimate of historic sites and house museums. In those early days, Woodlawn was chiefly prized as the genteel home of Nelly Custis, the adopted daughter of George Washington. In addition to guided tours, then as now, the site offers teas, is rented for weddings and hosts an annual needlework exhibition (now in its 49th year). But, while Woodlawn’s connection to George Washington was its salvation, it has also been its limitation. With Mount Vernon a 5-minute drive away, what did Woodlawn have to offer its roughly 16,000 annual visitors except the coda to a greater story?

In 2008, I was charged by The National Trust with reinventing this lovely, yet overshadowed, deficit-operating and increasingly superannuated historic site. The conventional approach would have been to hire a consultant, create an ambitious master plan and then figure out how to implement (read:pay for) that plan. But I had inherited a stack of previous consultants’ reports which were, literally, gathering dust on a shelf. The consultants weren’t at fault, but the fundamental premise was flawed:let’s ask museum professionals to transform a historic site into something completely alien to their knowledge, skills and abilities. And then ask them to raise millions of dollars to do it.

The nice thing about being a downtrodden site is that while you are trying to figure out what to do next, everyone in the immediate world has a big idea. At Woodlawn, I listened to all of them, even when the idea was “beg Mount Vernon to take it back.”(I wasn’t too crazy about the water park idea, either). The most intriguing proposal I heard was, “what about sustainable farming?”Not only did this fit the Trust’s core value of sustainability, it had the added advantage of being true to the site’s history.

I knew just enough about farming to know that we, as preservationists and museum professionals, weren’t going to pull this off by ourselves. But letting people in my community know that we were open to ideas allowed for the intended miraculous effect: a sustainability advocate introduced to me to Michael Babin, co-owner of the Alexandria-based Neighborhood Restaurant Group (NRG). Michael had the vision—a nonprofit venture aimed at training young growers, educating kids about good food and scaling up the local food economy by coordinating sales and delivery of the area’s sustainably raised foods to restaurants, schools, groceries, not for profits and consumers—and Woodlawn had the land. On the practical side, Michael also provided (through his restaurants and affiliated businesses) a core market, a network of slow food advocates and culinary junkies, deep knowledge of the food industry and (drumroll) start-up funding. And so Arcadia was born. At our November launch event, over 500 people showed up to celebrate the mission, enjoy myriad forms of charred pig and experience a fine (if chilly) fall day at “the farm” 9 miles from the Capitol. Soon afterward, Woodlawn entered into an agreement with NRG’s Star Catering to become the site’s exclusive caterer, which will allow us to “brand” events at Woodlawn as part of a consistent sustainable-heritage-edu-culinary package.

In the first year, Arcadia will start by farming six acres, emphasizing heritage varieties, before branching into larger scale crops and a distribution hub as land is cleared and becomes available. The beehives arrived last week, and director Erin Littlestar has declared “there will be chickens!” (And, yes, my little curatorial heart skipped a beat). We will adapt existing interpretive programs and material to the story Arcadia supports to begin with, and develop new programs that allow us to complement the activities of the farm as it evolves. Within three years, Woodlawn projects a substantial increase in revenue from events, while The National Trust will continue to work with Arcadia to expand farming, educational programs and hospitality services slated to cover 100 acres of our 128-acre site in five years. Hopefully Michael will have his new restaurant at the site long before then.

Reinventing historic sites for the 21st century may require abdicating a lot of the absolute intellectual and material control we are used to having. Rather than invest in a vision based on a stakeholder and staff-driven process and then see if anyone out there is interested, we can also start by identifying the needs and opportunities in the community, and determine what role we can play in fulfilling them.Then we can begin to reposition ourselves as multivalent resources, working with partners who have the talent, knowledge and resources to help us to reach new audiences—even when it falls outside our usual conception of ourselves.

And, please: not every site should be a farm! Michael’s project is a great match for Woodlawn because the site was defined as a farm all the way back in Washington’s time (if not before). Arcadia allows us to align our history with today’s community.

I will trek out to Woodlawn, come spring, video camera in hand. Stay tuned for footage of the Woodlawn/Arcadia experiment, and an interview with Laurie and Michael!

Bravo/a. What a marvelous process and result. The environmental sustainability movement is a gift to historic sites – it provides powerful relevancy that is immediately connected to many aspects of most sites' histories. I look foward to your updates.

Check out the museum group for historic farming and preservation:

http://www.alhfam.org/