This article originally appeared in the March/April 2011 edition of the Museum magazine.

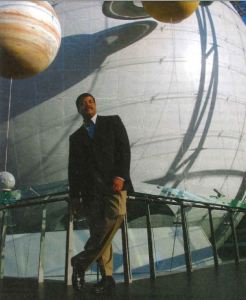

Museum director, astrophysicist and television personality. There are not many who claim to be all three at the same time. Neil deGrasse Tyson, the Frederick P. Rose Director of the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History and host of NOVAScienceNOW on PBS, is likely the only one in existence. The affable Tyson passionately advances the cause of science literacy in his museum and on the air, as well as in writing. He is also a bit of a futurist, having served on a presidential commission that studied the future of the U.S. aerospace industry. Elizabeth Merritt, director of AAM’S Center for the Future of Museums, invited Tyson to train his futurist’s eye on our field, musing on how museums can influence the next generation and help to change the world. Tyson will be the keynote speaker at the AAM Annual Meeting in Houston, May 25.

The role of museums may be fundamental to any hope or expectation that we can occupy a scientifically literate country in the future.

Museum: I’m going to start with one of my favorite questions to ask interesting people in interesting jobs. How did your experience in museums as a child influence the course of your life and your choice of career?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Entirely. One hundred percent. A simple visit to the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City as a kid at age 9 on a family weekend trip set me on a mission to become an astrophysicist. It would take me about two years, between age 9 and II, to formulate in my head the idea that my love of the universe could become a career. Because at age nine, you’re not thinking career; you’re just thinking what feels good and what’s fun to do. By age II, it was a career trajectory, and I credit the museum for igniting the flame within me to follow that course.

What kinds of museum experiences do you think have a really big impact on children and what they’re passionate about?

Having been project scientist of the reconstruction of the Hayden Planetarium into what is now the Rose Center for Earth and Space, containing the Hayden Planetarium, I’ve had a lot of occasions to think about the forces that operate on a visitor. There’s a lot written about what makes a good science exhibit, and I’m at odds with many in this regard. The typical discussion involves an exhibit capturing some science theme or some sort of curriculum point, and the kid engages with that exhibit kinetically-there’s a knob, a level, a foot pedal. Afterward the museum offers a little survey and says, “What did you learn from that exhibit? What principles of science matter to you from having had that encounter?” My personal view is that that’s asking way too much of an exhibit. You’re trying to get kids to learn science in the few hours that they’re visiting your museum? They’re spending years and years and years in school with books and teachers and homework and exams, and you want them to actually learn something testable on this field trip? I think it’s not only wrong to expect that, it misuses the medium. In my judgment, the role of a museum exhibit is simply to ignite a flame. The exhibit should be so fascinating intellectually (it could be physically fascinating as well) that you say, “Wow! I want to learn more about that.” Then the kid goes off and gets books and watches TV shows and rents videos or documentaries, and all of a sudden takes off, having been launched by the exhibit. That’s not the kind of experience that you can give an exam on.

Ask anybody what is the most memorable museum moment of their lives. In practically every case, they will cite a museum exhibit that satisfied several criteria. One of them is that it was bigger than they were. They walked into or were surrounded by it, or had to turn their head in multiple directions, or somehow experienced it with their entire sensory toolkit. My childhood experience in a planetarium . was completely immersive. It was bigger than I was. It surrounded me. It occupied all of my senses. Two, the experience was so engaging that they could not help but want

more for having done so. Ask anyone who has been to the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago what their favorite exhibit is, and it’s going to be the coal mine. Why? Because they’re in a coal mine! It’s an exhibit all around them. That’s what they remember the most. It was not an exhibit box that they walked up to and pushed buttons on. You go to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia and ask people who were kids and went through there, “What’s the most memorable exhibit?” It was the living heart that they walked through. And they had these low-frequency pulses, and you felt the heart. After you walk out the other side of that exhibit, are you going to give them an exam and say, “What is the left ventricle?” No! You could. Go ahead. But don’t believe that’s somehow going to decide whether that exhibit was successful or not. Success should be measured by what is the difference in ambition triggered by that encounter.

Various philosophies of exhibit design and learning have shaped museums over the past several decades. How do you think that AMNH and museums, in general, have changed from when you were that 9-year-old boy having that seminal experience?

With regard to collections-based museums, if you go back 100 years or a little longer, exhibits were typically displayed cabinets. You’d put your artifacts on display, and you’d tag its ear or you’d put a little label on it, and it would be a “cabinet of curiosity.” One of the tactics of exhibit display that the American Museum of Natural History pioneered is creating a context in which you can receive these artifacts. Thus was born the diorama. You’re not just looking at a stuffed lion; you’re capturing the mood and the scene and the lighting and the environment in which you would find that lion if you saw it in the wild. The AMNH collection of dioramas was able to transport the visitor in ways simple cabinets of curiosities could not. That has become the standard of how you display artifacts that can be put into this kind of context.

A more recent change is being more sensitive to the kinds of visitors you might have: for example, having exhibit labels in multiple languages. Another change is you need to be a little more succinct about exhibit copy. There’s only so much text a standing person can read and absorb.

If you shorten the text, yeah, sometimes you forfeit content, but more people read the text, so your net impact is actually greater. I look at some old exhibits and there’s something like seven paragraphs of information in 12-point type. I’ve never seen anybody stop and read it, except for the most diehard of museum visitors. And there are other tactical issues like the level of the exhibit copy. Can a person in a wheelchair read it? Is the lighting angle such that if you’re short, it puts glare on the screen? In other words, what’s the average height of the person that the exhibit is perfectly conceived for?

You’ve spent some time as a futurist. In 2001, you served on a commission that studied the future of the U.S. aerospace industry. If you turn your forecasting skills to the future of the museum sector, what are some of the forces shaping how we will change in the next century?

There’s always the assumption that whatever you were in the past, now you have to be different. That’s not always the case, and I’ll give you an example. One of the values of the American Museum of Natural History to the public it serves its neighbors as well as its far-reaching community-is providing continuity. If you went to AMNH as a kid, you have a certain memory of the most significant exhibits. If every five years we said, “Let’s take out all exhibits and put in new ones,” what we’ve done is broken a chain of continuity between one generation and the next. If you have kids now, you come back to the museum and say, “Oh, little Timmy, little Mary, check this out when I was a kid I saw this.” That’s part of the chain of continuity from one generation to the next. There are some exhibits that were just so well done at their time that you maintain them as part of what you might think of as your fundamental collection, your fundamental displays. Yes, you change other things, because not all exhibits are equally profound, well made or timeless. And you change some exhibits because you want to keep people coming back. That’s the ideal role of traveling exhibits, whether curated locally or curated elsewhere. They allow the museum to have a new encounter with the media because there are press releases, opening night, that sort of thing. And it reminds people that you have this cultural institution in their backyard that is deserving of their attention. So I think it’s a combination of what is old and what is new that makes the museum have meaning across generations within a culture.

If you were imagining what AMNH would be like in, say, 2061, what elements would you maintain and what do you think might be different?

One of our emergent goals in the last couple of decades is to present science with a social conscience. We recognize that science is not just some separate activity engaged by scientists, but that it is a fundamental part of what it is to participate in modern culture. An institution such as a museum has a responsibility to empower the electorate to make informed, scientifically literate decisions about their lives. If in 2050 we were delivering the same messages, either we’ve failed at affecting change in society and still needed to give those messages, or we just got left behind and we were no longer on the frontier of what mattered in society.

Let’s get even more specific. If you were catapulted forward so years in time, how would you want to be able to describe the world? What’s your vision of that preferred future that you have empowered people to build?

Science illiteracy is rampant in America. That alone is not a problem, provided the person who is scientifically illiterate knows this and seeks to correct it. The problem comes about when you have people in power who are scientifically illiterate making decisions in the absence of the insight that science literacy brings you. That’s a recipe for disaster. The role a museum can play is providing informal science education, as distinct, of course, from what would go on in a classroom. The two together- formal education that goes on in schools and informal education that goes on in museums-can catch both sides of your mind. Maybe you’re not good at science or you don’t like science as learned out of a textbook. But you can’t tell me you don’t like walking into the coal mine. You can’t tell me you don’t like what happens when they dim the lights and the stars come out in the planetarium. Nobody doesn’t like that. Nobody isn’t charmed and enchanted and enlightened by those encounters with the physical world. So the role of museums may in fact not only be auxiliary to what happens in school but fundamental to any hope or expectation that we can occupy a scientifically literate country in the future.

Comments