This article originally appeared in the July/August 2011 edition of the Museum magazine.

The night after my first day of teaching museum studies in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), I had a bizarre dream. The Emirati students with whom I had spent the day in Abu Dhabi were suddenly in my classroom in Berkeley, Calif. Instead of wearing their black hijab, which covers their hair and part of their faces, the women were uncovered. I didn’t recognize any of them. We walked down into the catacombs of Rome, wandering until we emerged onto cobblestone streets in Jerusalem. I kept checking my gas tank to make sure it was full. Then I was alone washing dishes.

It’s amazing what the jet-lagged mind can conjure after a 19-hour flight followed by a full day of teaching a workshop on the nature of museums and cultural identity!

The museum studies course I teach in the UAE is the brainchild of Salwa Mikdadi, an accomplished curator and longtime advocate for the arts community in the Middle East. In 2010, Mikdadi forged a collaboration between the Abu Dhabi-based Emirates Foundation for Philanthropy (where she heads the arts and culture division) and John F. Kennedy University (JFKU) in Berkeley. Mikdadi’s vision is to provide future Emirati museum leaders with a global overview of museum functions and opportunities relevant to the UAE. “The course aims not only to introduce new theories and practices in the field but also to initiate discourse on the role of museums in preserving local culture while serving diverse communities in this fast-changing world,” she says.

Working with Mikdadi, my JFKU colleagues Susan Spero, Melinda Adams and I developed a five-month introductory online museum studies course. It is punctuated by two intensive week-long, on-site workshops offered in the cities of Abu Dhabi, Sharjah, and Dubai.

Teaching museum studies in the UAE has been much more meaningful for me than merely delivering a curriculum. A classroom composed of an American professor and an Arab student body is bound to stimulate profound instances of cultural interaction. The interpersonal exchanges I have had over the past two years with 25 young Emiratis (as well as two Palestinians and one French student of Tunisian heritage) have challenged my own cultural assumptions, teaching philosophy and techniques. They have motivated me to think more deeply about why I believe that museum studies can be a provocative forum for “soft diplomacy.”

Founded in 1971, the UAE-a federation of seven Emirates along the Arabian Gulf_:_has one of the world’s highest GDPs, due to its enormous oil and gas reserves. The relatively new nation is attempting to diversify its economy by investing in an educational and cultural infrastructure fashioned largely by consultants from other Middle Eastern countries, Europe and North America. Projects include several universities; mega-branches of the Louvre and Guggenheim (due to open in 2013); a towering Zayed National Museum (planned with a team of curators from the British Museum); 19 existing museums of art, archaeology, culture, science, and history in Sharjah; and many others.

The nation’s desire to develop a corps of Emirati museum professionals to take charge of these initiatives is strong. UAE founding father Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan once stated: “The prosperity that we have witnessed has taught us to build our country with education and knowledge and nurture generations of educated men and women.” In 2005, Sheikh Zayed’s son encouraged the creation of the Emirates Foundation for Philanthropy to support “youth leadership, knowledge creation and society and culture.”

The museum studies course, now in its second year, supports these themes by emphasizing contemporary museum management, curation, interpretation, collections care and audience development. Applicants for participation in the course undergo a competitive process that gauges criteria including their knowledge of English and their interest in advanced study. The students who ultimately receive admission are typically practicing museum educators and curators at regional museums, as well as recent graduates of local colleges interested in museum careers. Most are in their early to mid-20s, with a few who are slightly older.

Before I arrived in the UAE in February 2on, the 15 Emirati students in the course’s second section were already actively posting on the class website, offering up ideas about museums as metaphors for life, society, the universe. To bring things down to earth, I began my onsite teaching with a presentation about the meaning of museums in my own life, sharing examples of how visits and my own work in museums have nurtured my passion for the field. Passion, after all, spurs most museum careers.

Alongside stories of childhood journeys to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, N.Y., and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., I projected an image of the first museum souvenir I ever owned: a small reproduction of a Paul Gauguin painting inscribed to me on my 6th birthday by my grandmother. Then, from a carefully packed box, I removed the actual print, passed out IS pairs of white cotton gloves and circulated the tattered souvenir for the students to handle.

Sharing my story and then trusting the students to touch such a delicate object from my personal collection established that we were going to cover far more than the basic techniques of collections stewardship during our week together. I wanted the students to bring emotion to our subsequent discussions. By the last day of class, students were reciprocating by sharing similar personal treasures: One played for us an audio recording of her father telling the story behind a family heirloom (a carpet); another brought in traditional fermented fish-infused Emirati bread that triggered a nostalgic reaction. She also shared with us her fencing glove, evidence of her athletic achievements and all the more interesting to me since she attended class with her face fully veiled. Still another student showed us her grandfather’s passport, a precious item from the era before the UAE existed when those lucky enough to travel did so under the authority of Great Britain.

An exercise like this might seem childish; after all, didn’t we already do “show and tell” in grade school? Moreover, when taken in an academic museological context, sharing family stories and common heirlooms may even negate the very idea of a museum. Our traditional conception is that museums collect unusual, unfamiliar or rare objects that are viewed communally and set within a larger story. Most publicly displayed treasures or iconic objects are deeply tied to the web of a community, a nation or beyond. As an American who grew up with regular exposure to museums, I have an intimate relationship with their objects and the souvenirs from my visits to them.

What struck me about the Emirati students is that they came of age in a nation that didn’t even exist until 1971, much less have museums. Theirs is not a museum-going culture, yet now the UAE is hosting one of the most ambitious museum-building endeavors on the planet. How, I wondered, do young Emiratis connect deeply to important communal objects? Where are they exposed to them? Where does their sense of their nation’s artistic and material culture come from?

The answer, I learned, was through family memories passed on by relatives and fostered at home. I also learned that young Emiratis are concerned that their nation’s dizzying transformation is erasing these memories and familial ties. After all, Dubai feels like a pop-up city where construction occurs so rapidly that a streetscape can literally transform overnight. Since the art and artifacts to be featured in the Louvre and Guggenheim branches will likely not resonate to family, ancestral memory or personal achievement (as in m the case of the fencing glove). their emotional impact is unclear. The new museums are not being created from within Emirati culture, so the Emiratis must find ways to develop relationships with new kinds of communal objects {like masterworks from the Louvre) in order to foster passion for their museums.

The “show and tell” exercise demonstrates how personal even the most consummate professional’s connection is to museums. As one student, Sharjah museum educator Alya Burhaimi, put it: “Inviting nationals to talk about how Sheikh Zayed affected their lives, giving their opinion about what they think and feel during the planning of the Zayed National Museum, would greatly influence all of us living in the UAE. It is important that our voices get heard and that we are part of the process [of creating the new museums], because we are the nation.” Another student, 22-year old Maimunah Abdulla, echoed ideas in the assigned reading and posited that all museums should display objects in such a way that allows visitors to make personal links to them.

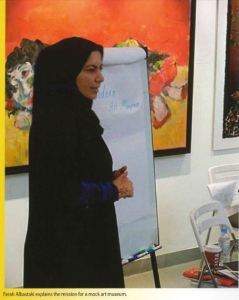

I facilitated another exercise that further probes the meanings of objects. I divided the students into four museum groups: art, science, history and children’s. Each group received a bag containing the same set of 25 objects, including a pair of dice, a few Pokemon stickers, a plastic tiger and a packet of sugar from a nearby Starbucks (yes, it’s everywhere). The assignment was to use these random objects to create an exhibition. The groups could design their show in any way that they wanted as long a; it was congruent with the basic subject area and mission of their museum. They were permitted to put some of the objects in mock storage, properly inventorying and cataloging them, but had to account for all 25 objects.

Young Emiratis connect to important communal objects through memories passed on by relatives and fostered at home.

In two-and-a-half hours each group had synthesized a coherent storyline. For the art museum, the tiger stood outside as an entry sculpture. In the science museum, it was the centerpiece in a walk-through diorama. It adorned the history museum (which the students set up as a historic house) as a prominent citizen’s hunting trophy and lived in a petting zoo at the children’s discovery center. The sugar became a modern artwork, a lesson in unhealthful eating, evidence of historic trade routes and glitter for projects in the discovery center.

Interestingly, unlike my California students’ interpretations in a similar ice-breaker exercise, not a single Emirati mock museum contained an income-generating gift shop or a cafe (although one had a corporate sponsor). Yet, like students everywhere, the Emiratis incorporated interactive educational programs, the idea of recycling and environmental stewardship, contemporary art installations, and fictional collectors and visitors into their mock museums. Even though they didn’t grow up in a nation with an active museum community, through travels, reading, and interactions with others, the young Emiratis have a visionary sense of museums’ potential.

Like the discussion about objects and personal meaning, this exercise in rapid curation (I joked that operating on UAE time, the students had completed in two-and-a-half hours what might take a professional museum five or more years) serves as a catalyst for a larger discussion. It implies that a museum is a clean slate and that exhibition creators do not have to concern themselves with internal and external politics, budgets or confining gallery spaces. In the real world, of course, museums don’t operate this way. They also don’t have the opportunity to move as fluidly between disciplines. The cultural meaning of objects is more fixed, especially as they become endeared to a community. Any museum that has removed an iconic object from display-even for a short time-knows this.

Yet in the UAE, the opportunities for creativity and playfulness seem endless. Will these students—who quite possibly will be the future leaders of the UAE’s museums—have the freedom to be this open-minded if they curate exhibitions within their new institutions? To which stakeholders will they be beholden? In the future, I believe they will need more free-form exercises like this to help them retain their creative drive and the potential of their new museum culture.

When asked by a reporter in Dubai how Emirati museum studies students differ from their counterparts in America, I hesitated. Other than the fact that most of the women wore a hijab, and some were more comfortable speaking Arabic than English, they had similar aspirations to those of my students in California. I had at first thought that the Emiratis would be less willing to debate in class. I was wrong. They dug into the meat of the material and challenged me with questions like: “What if a museum inherits a collection that someone else has put together but doesn’t make sense?”; “What does it mean that an object is ‘museum quality,’ and who gets to decide this?”; and “How does the personality of the staff impact the way objects are curated or exhibited?” Their questions are relevant to museum practice everywhere. The students understand that power relations within a museum are political and fraught with value judgments about how to interpret art, history and even the spiritual essence of an object.

Many Americans have asked me what it was like to be a jew teaching in an Islamic country. Perhaps my bizarre dream conflating Abu Dhabi, Rome and Jerusalem touches on my subconscious confusion about just how much my personal life should intertwine with teaching museum studies. But I quickly learned that any worries were rooted in my own family history and cultural assumptions. It simply wasn’t a big deal, although some students were curious. How I loved engaging questions such as “What is a rabbi?” and (manna to all teachers) “Where can I learn more?” I then posed questions of my own about imams and the role of the ghutra (male headscarf) and abaya (the black, robe-like traditional garb worn by women in the UAE). Through lunch-time and after class conversations, my Arab students expressed their own worries about Westerners’ misconceptions of their dress, customs and religion and how these might be addressed in museum programs and exhibitions for foreign visitors and workers in the UAE.

My colleague Susan Spero remarked after her onsite teaching in Sharjah: “One of the biggest gifts we give museum studies students is the tools to critique museums and therefore improve them. They can never see museums again in the same way.” The day after the formal classes ended in February 2011, I drove to the oasis city of Al Ain with three students to visit several museums. We disliked some of the displays and admired others. Like all good museum professionals, we inspected the quality of the installation, the interpretation and signage, and even the friendliness

of the front-line staff.

On display in one gallery was a vitrine of historic Korans. First, we critiqued the cases as well as the condition of some of the rare items. Then the conversation took a significant turn. I told them that I had tried to

read two different English translations of the Koran before my trip, but confessed that I couldn’t understand them. One of my companions tried to decipher some of the texts on display for me and explain how they are used. Then she told me that she was curious about the Bible, prompting me to recite the first few sentences of Genesis from heart. Here was a potent example of how an object viewed communally in a museum gallery can propel a higher level of connection.

Museum studies is commonly perceived as a curriculum of learning objectives articulated in syllabi and anchored in standards advanced by professional organizations. But when experienced as cultural

interchange it really becomes much more than that. It echoes the power of museums as safe places where

objects inform who we are and who others are.

Comments