Today’s guest post is by Elissa Frankle, an education consultant at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. When not coordinating and raving about the Children of the Lodz Ghetto Citizen History project, she trains law enforcement officers and judges and coordinates public survivor programs for the museum. Elissa can be found on Twitter @museums365.

Forecast: In the history museum of the future, curators’ work will be driven by our audiences’ curiosity, and their preference for inquiry over certainty.

In the age of the twenty-four hour news cycle and a well-researched, well-policed Wikipedia, museums like to believe that we still have the advantage of being Authorities. We know how to do Research. We know how to pose the Right Questions. We know, most importantly, how to Give Our Visitors The Answers.

Citizen History is an experiment in finding out what happens if we trust our visitors enough to allow them to bring their diverse perspectives and boundless enthusiasm into the research work of the museum and share our authority.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleCitizen History is similar in concept to Citizen Science, in which a museum or other research institution invites participants to go into their backyards to count birds, for example, or sample streams. The institution sets the question, determines the parameters of the study, may provide training, and checks the results—but trusts participants of various levels of skill to collect the actual data.

Citizen History opens up a museum’s existing data to participants and, through scaffolded inquiry, invites participants to draw conclusions to answer big questions. At the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, for instance, our Children of the Lodz Ghetto project invites citizen historians to mine our data, challenging them to find out what happened to 14,000 students from the Ghetto who signed a school album in 1941. The questions we pose are: What was school like in the ghetto? How were students organized? Where did they live in relation to the schools? Did the fate of a given student depend, in part, on where he or she lived or went to school? Our databases may contain the names, dates, and places that can help answer these questions, and enable us to properly memorialize these individuals.

|

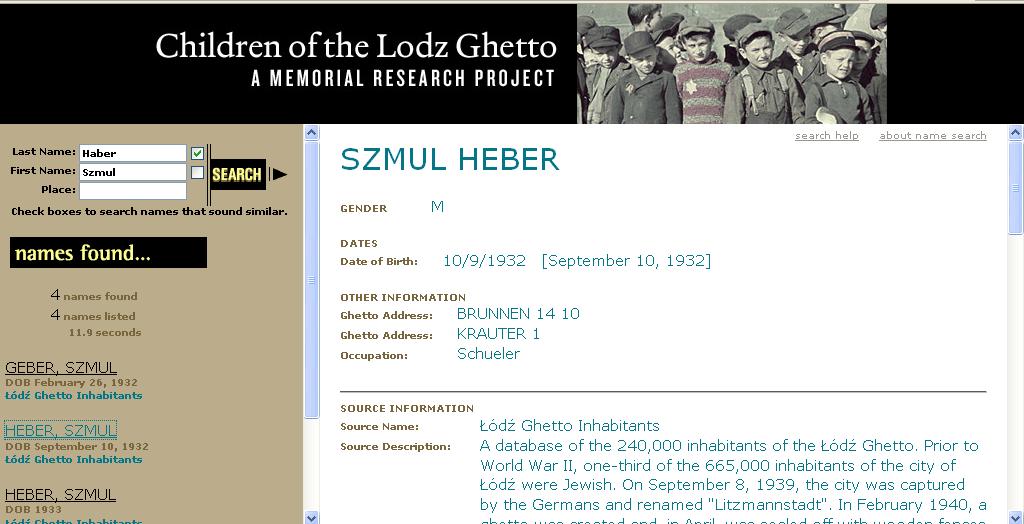

| Screen shot of the project. |

We currently have 5,000 names on the project site, and provide the information we have on each: the name as it was signed in the album, the number of the school the student attended in the fall of 1941, and a general age range of students in that school. We designed a user interface that helps citizen historians organize their research: for each student there is a “workspace” divided into five chronological sections, and each section contains fields for specific information researchers are challenged to seek out: given name, date of birth, address and date of address change, parents’ names, name of labor camp to which the student was sent, etc. We link many of the museum’s searchable online names databases related to the Lodz ghetto to the relevant chronological stage, facilitating the search for snippets of information to fill these fields.

|

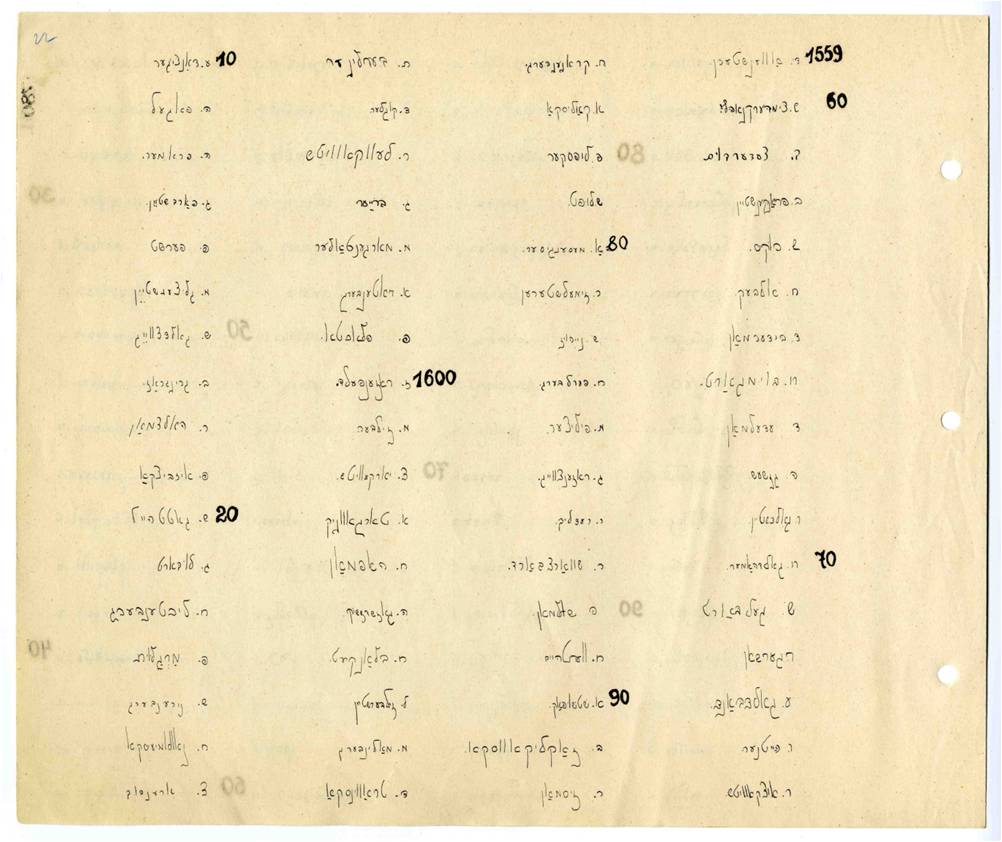

| Yiddish signatures |

One of the greatest difficulties facing citizen historians is the messiness of the data: students might have gone by many different names, but only signed one—and sometimes signed in Yiddish, or with a first initial and last name only. There may not be any information on a given student. While these are no different from the frustrations that professional historians face, it does mean we have to work to manage the expectations of citizen historians (there will not always be information, but don’t give up!) and encourage them to be flexible and use their imaginations (what if that last name Berlinska signed in the album appears as Berlinski in the database?).

The secret weapon in Citizen History, mitigating both user frustration and institutional concerns, is the back-end facilitator (in this case, me!), who is responsible for enforcing institutional standards for accurate research and maximizing user satisfaction with the interface. The museum has high standards for precision and accuracy in disseminating the history of the Holocaust; rightly so, since inaccuracies are often used to fuel the fires of Holocaust denial. No information generated by the Citizen History project is made available to the public until it is quality checked by me.

This is a huge job: I proof the work of citizen historians by checking the online sources they cite, respond to all submitted content with a rating of its accuracy (confirmed, possible, invalid) and provide an upbeat, encouraging comment while gently pointing out (if necessary) that the user has jumped to conclusions without evidence or missed a possible name match in a database search. I encourage citizen historians to go through multiple revisions until he or she has learned the correct methodology for moving from a question to a data point to a narrative. The next stage of the project, launching this fall, will also encourage citizen historians to organize into research groups to tackle questions they have generated themselves.

In the future, we hope to turn some of the work of facilitation over to “expert users,” who have established their credibility by using the site extensively and accurately. I can imagine a future in which this research process lies entirely with citizen historians: self-organizing research groups submitting work that is checked by an expert user, and integrated into museum content. This will require a high degree of trust on the part of the museum—but so far, our most dedicated citizen historians have proven themselves to be accurate and thorough, in other words, trustworthy users and guardians of the memory of the students who signed the album.

We believe that Citizen History can encourage more people to become historians, or at least make history and historical thinking more accessible to participants. If we don’t talk at our visitors, but instead talk with them, listen to them, find out what makes the curious—we welcome them into the conversation and open up the possibility that history is interesting, or, even fun. And the museum benefits from this shared authority as well: maybe the findings of our Citizen Historians will challenge our assumptions about the Lodz Ghetto. Maybe they will pose questions we haven’t yet thought to ask.

Excellent article — fascinating work on the Lodz Ghetto and thoughtful notes on the implications for our sector.

The new Zooniverse project, http://ancientlives.org/ is another fine example of 'Citizen History' in action — a very useful term