This week’s guest post by Erik Ledbetter, principal of Heritage Management Solutions and special adviser to the Forecasting the Future of Museum Ethics project currently underway in partnership with Seton Hall University’s Institute of Museum Ethics.

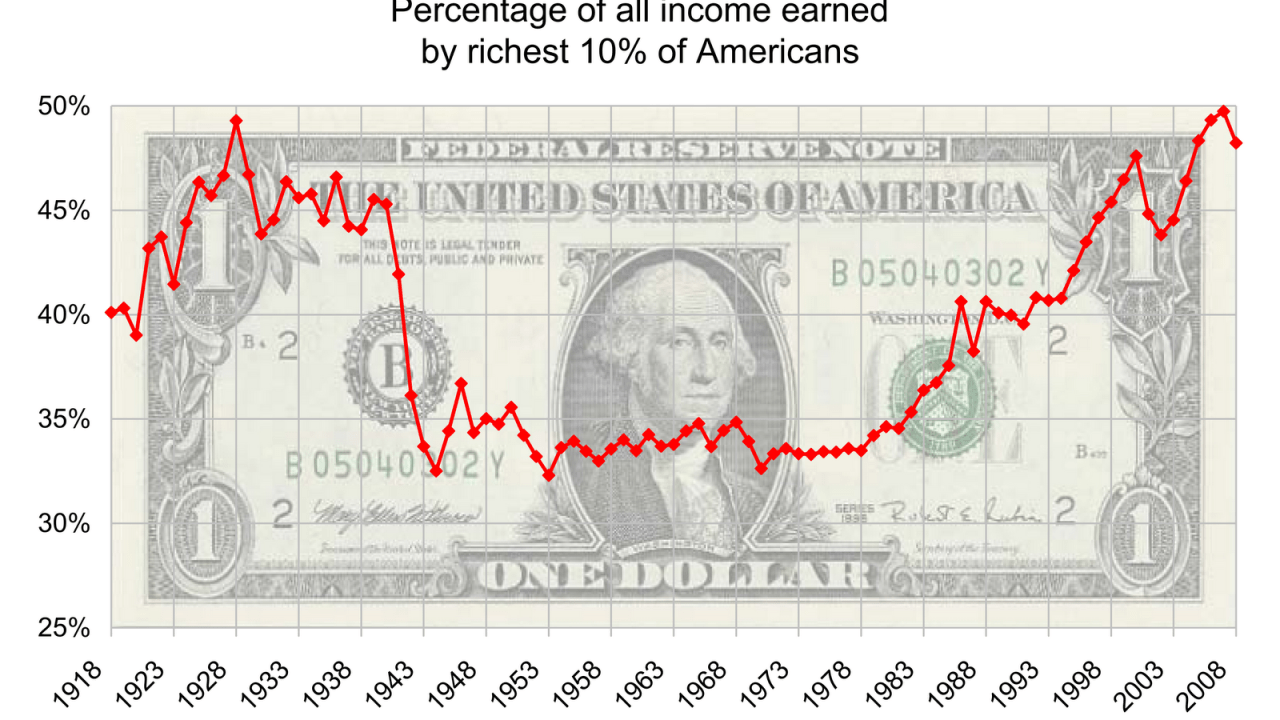

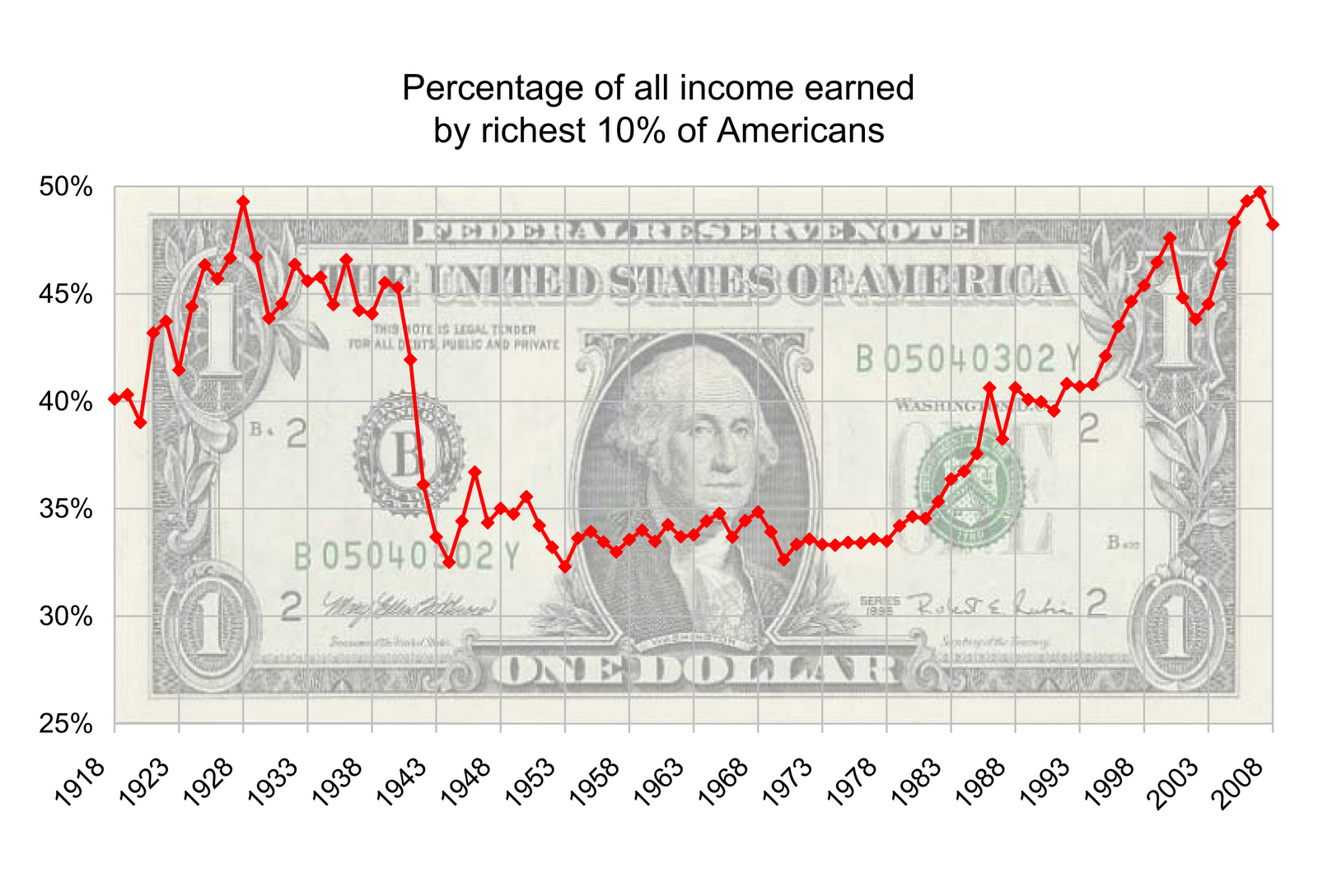

We are living in a new Gilded Age. Like the 1870s and 1880s before them, the 2000s and 2010s are marked by a vast increase in concentration of wealth and a yawning gap between the top one percent of society and the rest. In the September 2011 issue of The Atlantic, journalist Don Peck notes that as early as 2005

“the richest 1 percent of households earned as much each year as the bottom 60 percent put together; they possessed as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent; and with each passing year, a greater share of the nation’s treasure was flowing through their hands and into their pockets.”

Since then, the Great Recession has only accelerated the hollowing out of the American middle class. “Median incomes declined outright from 1999 to 2009,” Peck reminds us. “For most of the aughts, that trend was masked by the housing bubble, which allowed working-class and middle-class families to raise their standard of living despite income stagnation or downward job mobility. But that fig leaf has since blown away. And the recession has pressed hard on the broad center of American society.”

|

| Source: Emmanuel Saez |

The decline of the middle class and the reemergence of a true American plutocracy will have, I predict, some interesting consequences for museums. In an era when public budgets and private household wealth are both contracting, museums’ business models will be increasingly upset. For decades we have worked hard to diversify our funding sources. As the Great Recession grinds on, however, it is ratcheting down nearly all of our supposedly diverse income streams at once. Declining household wealth puts pressure on admissions and membership revenue; tight federal, state and municipal budgets crimp grant income.

Increasingly, the last remaining source of income growth for museums will be that special one percent—the plutocrats of our new Gilded Age. But are the new super-wealthy going to be interested in funding existing museums? History and present trends alike suggest not. In the first Gilded Age, the plutocracy preferred establishing its own museums to funding those which were already there. New institutions with names like Frick, Clay, Walters, Huntingdon, and Freer were founded right and left. We see the same behavior emerging today. After playing the art museums of Los Angeles off of one another in a bidding frenzy for his collection of modern art, Eli Broad fooled them all by electing to establish his own museum. Alice Walton is bringing the finest American art to come on the market in the last two decades to her new museum in Bentonville. Ron Lauder’s outstanding collection of German and Austrian expressionists can be seen not at the Met or MoMA, but at his own Neue Gallerie museum in New York.

Nor is this trend limited to art museums. In Ohio, an entrepreneur is building a new private railroad museum complete with a purpose-build roundhouse and turntable to house, restore, and display his collection of historic steam locomotives. When complete, his facility will be superior to the majority of public railroad museums in the country. Yet it is strictly a private venture, and the terms, if any, on which it will be accessible to the public remain unknown.

What does all this have to do with museum ethics? Not to put too fine a point on it, I suspect that as our existing museums vie for attention and funds for the new plutocracy, some of our current fussiness about curatorial independence will go discreetly overboard. Current AAM ethical guidance places a premium on maintaining an arm’s-length relationship between museums and donors to avoid even the appearance of conflict of interest. But how can an existing museum compete when the donor could as easily found her own museum, and become effectively curator in chief, director, and chair of the acquisitions committee all in one? Answer: it can’t—unless, that is, it is willing to give donors considerably more sway over acquisitions and exhibit decisions than they presently enjoy. The same goes for loans—our present guidance is designed to create a total firewall between the lender of an object and/or financial donor to the show and the museum staff working on the content. When a handful of individuals control both the collections and the economic resources museums will need to thrive, however, will such guidance come to seem mere needless pearl-clutching?

Museums thrived in the former Gilded Age, and they may yet thrive in this new one—but if so, it is likely to be by setting some of their nicer scruples to the side, and learning again how to give a plutocracy its droits du seignior.

What do you think? In the coming decades, will pragmatism trump principle when it comes to donor relations? Should it? Will selective pressure favor museums founded and funded by the new economic elite? Read the next post in this series for a real-world illustration of this conundrum.

Thanks for this very interesting article – thought provoking and links to recent developments in Australia with the recent opening of the private museum in Hobart – the Museum of Old and New Art (MOMA)- getting great reviews but definitely a very different take on the 'public museum'.

Sorry its MONA

In the early 20th century, John D. Rockefeller, Sr. was the "new" plutocrat, a businessman whose only pleasure seemed to derive from his predaceous manner of buying and selling companies. His eldest son spent much of his life trying to atone for the "sins of the father", and we have much to show for it: Colonial Williamsburg, Grand Teton National Park, etc. I'm afraid the latest crop of plutocrats are so hollow, so devoid of scruples that there will be no such period of atonment to benefit the public at large. All the resources of the top 10% will likely go down in flames along with them.