This article originally appeared in the July/August 2012 edition of the Museum magazine.

Museums are living through extraordinary times, suffering from strained budgets, a drop in philanthropic support, dwindling government funding, shrinking endowments and a wide variety of internal challenges. As our institutions seek to define new avenues to sustainability, there is one option that has been adopted by some organizations: a merger.

The phenomenon of merging or forming partnerships and alliances with other museums is not a new one. Over the years, we have seen museums seek to preserve their assets and achieve their mission through such alliances. Recently, however, the popularity of mergers seems to be gaining particular momentum, with museums joining forces within the past two years in Florida, Texas, Hawaii, Maine, New York, Ohio, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Washington, D.C., and California, to name a few. Many of these are recession-driven, but some are mission-driven or the result of community initiatives.

Mergers can take different forms. Sometimes, several separate organizations dissolve to form a new legal entity. Other times, an existing nonprofit can acquire one or more others as wholly owned subsidiaries. These mergers usually include staff, facilities and/or collections. When the Baltimore City Life Museum closed in the 1990s, for example, their collections were transferred to the Maryland Historical Society. Similarly, the Phoenix Museum of History collections were subsumed by the Arizona Science Center in 2009.

In recent years, the financially driven merger has dominated. A merger can allow a struggling museum to stay alive and avoid closure and bankruptcy. A recent example is the South Street Seaport Museum in New York, which was taken over by the Museum of the City of New York in the fall of 2011 after a number of years of financial challenges. Under a special grant from the City of New York’s Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, the two entities are working on a turnaround plan for the ailing museum as a first step toward merger. This case is an example of the wisdom of good upfront planning.

Mergers have distinct legal implications and can have lasting impacts. There is always risk as well as reward. Museums are attracted by various benefits such as economies of scale; savings in administrative overhead; access to donors, members, facilities, talented staff and significant collections; and improved community relations. Yet risks abound, including confusion about brand image, leadership changes and staff layoffs, board struggles, unclear expectations, canceled projects and delays in accreditation. Community feelings can run deep, as many museums have a long history of service and respect. Merging requires careful financial planning, feasibility studies and good communication. It is also a lengthy process, sometimes unfolding over years.

Whether merger, alliance or collaboration, the primary motivation is to build on strengths.

Mergers are not always the answer. A less complex approach is to create an alliance or collaboration among organizations to share services. In one successful example, the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga has been providing administrative services to the nearby Hunter Museum of American Art and Creative Discovery Museum since 2001. The relationship extends to joint fundraising and marketing. Museums can also work together by collaborating on specific projects such as cross-marketing, sharing collections, touring exhibitions or joint programming.

Whether merger, alliance or collaboration, the primary motivation is to build on strengths. In 1992 the Essex Institute and Peabody Museum of Salem, Mass., merged into the Peabody Essex Museum, which today is a thriving organization thanks to the successful melding of exceptional art and cultural collections with libraries and historic buildings. In 2002, Philadelphia’s Balch Institute of Ethnic Studies merged with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP), uniting two nationally known research libraries with a common mission of documenting the American experience. The HSP was founded in 1824 and has built a manuscript collection of national importance, while the Balch, founded in 1971, has built collections that feature the ethnic, racial and immigrant diversity of our nation.

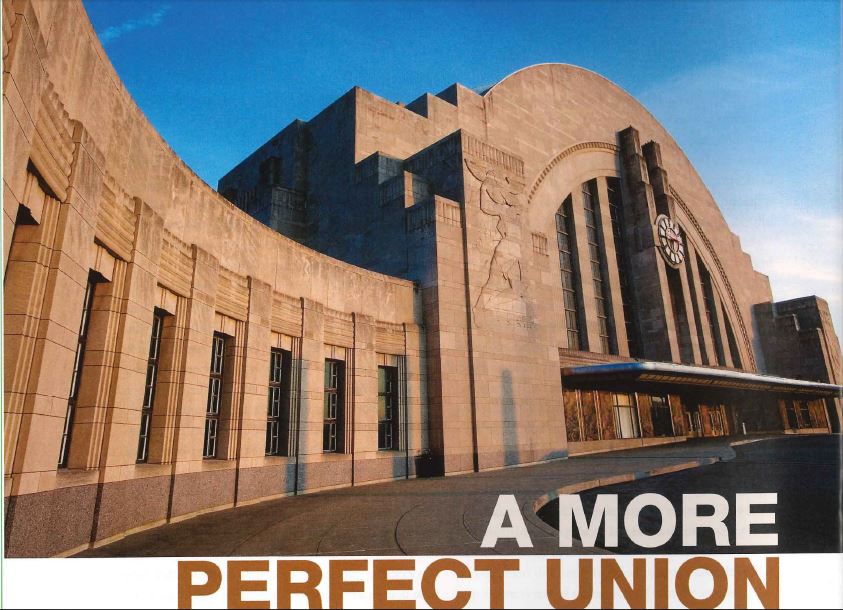

The most successful mergers create a blended organization that combines two or more existing institutions under a single governing framework. These unions are driven by a desire to better meet the museums’ mission. The Cincinnati Museum Center (CMC), governed under the auspices of the Museum Center Foundation, is the product of one such pioneering merger, evolving over several years throughout the 1990s and bringing together three well respected and formerly independent museums in the city: the Museum of Natural History and Science, the Cincinnati History Museum (formerly the Historical Society) and the Duke Energy Children’s Museum. The mission of the CMC is to “inspire people of all ages to learn more about our world through science, regional history, and educational, engaging and meaningful experiences.”

The three museums took up residence in the historic 1933 Union Terminal building owned by the city, which provided much-needed exhibition and program space. As detailed in a 2003 case study by LaPiana Consulting (a firm that assists nonprofits). the early years of this merger were difficult due to separate boards and staff, operating deficits and the lack of a strong plan for integration. In 1999, Douglass McDonald became president and CEO, actively integrating the organizations, making budget cuts and creating a new strategic plan with board and staff collaboration. The CMC has continued to thrive throughout the past decade and received a National Medal for Museum and Library Service from the Institute of Museum and Library Services in 2009.

Given the success of this alliance, it is not a surprise that Cincinnati’s National Underground Railroad Freedom Center began working toward a merger with the CMC in winter 2012. Open to the public since 2004, the center is dedicated to increasing awareness of the national story of freedom from slavery as well as focusing on a mission of “challenging and inspiring everyone to take courageous steps for freedom today.” Unfortunately, the museum has suffered consistent financial problems, facing annual deficits of $1.5 million and a real possibility of a permanent closing, according to a Feb. 12 article in USA Today.

Cincinnati Museum Center

With community support for their survival, talks began quietly to explore a merger with CMC. The boards of the two organizations agreed that the Freedom Center should continue to operate at its current location and maintain its mission while becoming a subsidiary of the CMC. This will allow the center to sustain its original mission and programming, which is unique and of national importance.

According to a detailed governance and management structure agreement, each entity will maintain separate boards, with dual board appointments serving to assure collaboration on strategic decisions and governance. To alleviate budgetary concerns, administrative functions such as finance, human resources, facility management, procurement and IT will be consolidated, eliminating about rs positions.

McDonald notes that this merger is characterized by active involvement and encouragement of the donor community and other stakeholders. Procter and Gamble, the largest employer in the region and a financial supporter of the Freedom Center, has provided an executive on loan to serve as chief growth officer, assisting with due diligence and strategic planning for the museums as they go forward.

Freedom Center Executive Director Kim Robinson says that this merger will have a “positive impact” on fundraising and help discover the “hidden treasure” of staff from both organizations working together on projects, improving infrastructure and taking other steps to “keep alive the broader story about freedom.”

From the CMC’s perspective, McDonald sees this merger as an opportunity to reach new national audiences and create traveling exhibitions. Some challenges of the merger, however, include creating a communications and marketing plan that allows for separate brands with an “invisible connection,” he says. A new capital campaign will include endowment gifts for both the CMC and the Freedom Center. McDonald suggests that museums considering a merger treat the endeavor as a “corporate process,” conducting due diligence, managing legal issues and drawing on the skills of board members with corporate experience. The board also needs to be a conduit for community concerns and an advocate for a sustainable model. Community conversations have been a hallmark of this process.

While the Freedom Center merger with CMC is largely driven by financial needs, the 2006 merger that created the Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas was inspired by common mission and community relevance. In 2009 the museum was the first-prize recipient of an award for exemplary models of nonprofit collaboration given by the Lodestar Foundation, a grant-making organization that encourages philanthropy. The Dallas merger was recognized for a successful collaborative process and for reinventing itself as an organization that optimizes its resources.

The Dallas Museum of Natural History served as the lead organization in the merger, first joining with Science Place and later incorporating the Dallas Children’s Museum. The initial merger was a logical step, as the science and natural history museums had similar missions and visitor and member demographics, and were physically adjacent to each other. In fact, they found themselves calling on the same donors. This was an opportunity to seek foundation and corporate funders’ assistance and support to pursue the merger.

President and CEO Nicole Small says that a preliminary step was forming a collaboration committee comprised of members of both boards. Fortunately, the boards of both organizations had members with corporate acquisitions

experience. Small, who was on the staff of the natural history museum at the time, has a business background including an MBA and experience in mergers and acquisitions. The integration occurred very quickly, she says, and donors were willing to provide necessary funding to cover IT and severance costs. It’s “clear that the community has to see success,” says Small; the newly opened Dallas Museum of Nature and Science began updating exhibitions right away. Despite being closed to the public in the early phases, the museum moved quickly to secure blockbusters such as “Body Worlds,” a highly successful traveling exhibition that displayed human bodies’ inner anatomical structure through a unique preservation technique.

What can museums considering mergers do to prepare for this critical decision? Following are suggestions from Douglass McDonald, president, Cincinnati Museum Center; Nicole Small, CEO, Museum of Nature and Science, Dallas; and Jim Richerson, president and CEO, Peoria Riverfront Museum, Peoria, Ill.

Get the best expertise: Seek specialized legal and business merger advice from trusted sources.

Find good leadership: Create a joint board committee to oversee the process and have a strong CEO leading the effort. Build trust among members of the merging entities.

Compatability: Ensure there is a match of missions and strategic goals. This will be the most important factor in convincing staff, donors and the community of the need for a merger.

Do no harm: Conduct due diligence investigations of assets and liabilities, facilities staff, membership, reputation and expectations for a merger.

Build stakeholder support: Institute community conversations about your goals and seek feedback and support. Work with staff to share information about plans and their role in the merger. Seek donor support to cover costs associated with the merger.

Implement carefully: Several museum leaders stress the importance of a good integration plan. Define governance roles and responsibilities, operating bylaws, structure and reporting, mission and program. Establish good internal and external communications; consider branding and naming issues; ensure transparency of decisions. Consider what administrative systems can be revised or consolidated. Allow sufficient transition time but move quickly to show early success and build momentum.

Consider timing: The best time to seek a merger is when there is no financial crisis but a clear benefit to the community to join forces.

Another very visible part of the Dallas merger process was the decision to move forward with expansion plans. In early 2013 the museum-re-named the Perot Museum of Nature and Science—will open to the public. (The family of billionaire businessman Ross Perot has given $50 million to this project.) This $185 million, 180,000-square-foot, sustainably designed project will feature state-of-the-art exhibitions, theaters, and retail operations.

In many ways, the Museum of Nature and Science is a success story. Not only did three museums merge, but within six years they surpassed their capital campaign goal. Fundraising has continued, as they build their endowment for new areas of growth. CEO Small credits “board vision early on,” which created the merged entity before the economic downturn and without a rescue mentality. Small says that their story has been “about growing, not shrinking.” Attendance and membership numbers are up, and new staff is being hired (although initially, redundancies did lead to layoffs, a phenomenon common to mergers).

Leadership continues to be an important factor in merger success. Small took the helm of the museum early in the merger at a time when Science Place had no CEO. She has successfully seen the project through integration and expansion over the past seven years. As community buy-in remains a critical factor for success, the museum has created a 70-member advisory board that serves to support the new entity.

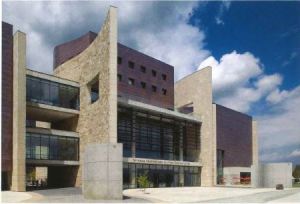

The Peoria Riverfront Museum aims to bring a strong economic boost to its region.

While Dallas and Cincinnati have merged governance and operations of existing museums, the city of Peoria, Ill., has created a different type of collaboration that demonstrates how a community can encourage the creation of a showplace museum rather than separately supporting a myriad of individual museums. The 80,000-square-foot, LEED Gold-certified Peoria Riverfront Museum opens this fall with the Lakeview Museum of Arts and Sciences at the helm as the lead organization and eight other entities joining it, including the Peoria Historical Society, Illinois High School Association, African American Hall of Fame Museum, Peoria Regional Museum Society, Nature Conservancy and Heartland Foundation (devoted to the history of square dancing). Each of these organizations has joined Lakeview in developing exhibitions and programs in the new facility.

According to Riverfront Museum CEO and President Jim Richerson, each museum will have a presence in the $150 million facility and representation on the board. They currently operate independently but retain the option of formally merging with the Riverfront Museum in the future. They will operate under memorandums of understanding that detail their involvement as exhibitors or in cross-marketing programs. For example, the high school association will have a gallery space at the new museum called “Peak Performance” with a focus on fitness. Richerson cites a “deep history of collaboration” in the city, noting that “so years ago, 26 separate organizations became the Lakeview Museum.”

Critical to this project is the strong partnership of Caterpillar Inc., the construction equipment manufacturer whose world headquarters are in Peoria. Caterpillar has invested in the development of a site called “the Block,” where the Riverfront Museum will operate adjacent to the new Caterpillar Visitor Center-creating an attraction for community members and visitors from around the globe at one location. Like many new museum projects, this one aims to bring a strong economic boost to its region through a mission “to inspire lifelong learning for all-connecting art, history, science and achievement through collections, exhibitions and programs.”

Richerson notes that collaborations such as the Riverfront Museum serve to attract significant funding from federal, state, county and local sources. The city donated the land, Congressional representation helped secure federal grants and the county passed a sales tax referendum bringing almost $36 million to the building project. The variety of public funding sources is a success and also “challenges the museum to show the public the value to community,” he says. The museum is developing metrics to measure the outcomes of this project. Richerson has also secured Affiliate status from the Smithsonian Institution, providing traveling exhibitions and long-term loans of Peoria-made artifacts, as well as attracting donors.

What are the impacts of mergers? In some cases, they are a way to save a museum or its collections from demise. In other cases, the collaboration deftly meets the needs of the community and matches the capacity of the donor base. With a proliferation of museums of all kinds throughout the country, communities should be taking a close look at what number of institutions is sustainable. A recent study by the University of Chicago found that the building boom in the cultural sector has occurred without clear analysis of community demand and ability to sustain these projects. New museums are being formed on a regular basis, and much time, effort and money goes into a start-up or even an expansion. Yet the reality is that competition may force collaboration if organizations want to achieve long-term sustainability. On the downside, mergers do cause the loss of identity and perhaps a treasured brand. They often lead to staff layoffs and can create confusion with donors, members, and the public. In general. though, with careful planning, a merger can serve as a viable means to long-term sustainability.

Martha Morris is associate professor and assistant director of the museum studies program at George Washington University and co-author of Planning Successful Museum Building Projects, Alta Mira 2009.