This article originally appeared in the July/August 2012 edition of the Museum magazine.

First of a four-part series

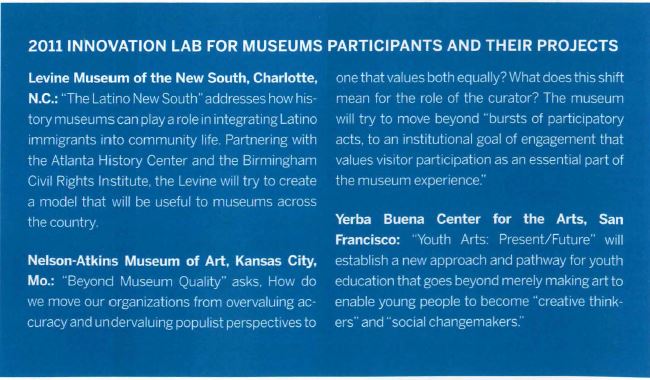

In 2011, AAM launched Innovation Lab for Museums, a grant-funded program enabling participants to incubate organizational innovation in a lab-like setting over 18 to 24 months. The program is structured to maximize creativity and innovation while minimizing risk, enabling museums to expand their vision of their future and what is possible. The first three grant recipients are the Levine Museum of the New South in Charlotte. N.C., the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Mo

Innovation Lab for Museums is a collaborative initiative joining AAM’s Center for the Future of Museums (CFM) and EmcArts for the Performing Arts, with funding provided by the Metlife Foundation. The framework was adapted from EmcArts’s highly successful Innovation Lab for the Performing Arts. Grantees were chosen from a pool of 33 applicants by a panel of leading thinkers from inside and outside the museum field.

CFM founding director Elizabeth Merritt will track the participants’ progress through the Lab over the next year. sharing what they are learning and suggesting how these lessons might be applied in museums in general. The objective of this series is to “scale up” the support provided by them Metlife Foundation so that it benefits the entire museum field.

An Overview of the Program

Museums are really good at continuity, not so good at change. This is a matter of some concern, because if (as the work of CFM suggests) the future will be significantly different from the past or the present, museums will need to change in order to thrive in new conditions. Hence the need for innovation-change that arises from questioning assumptions, disrupts old models of operating and has a real impact on a museum’s ability to fulfill its mission.

Meet the first class of Lab museums

The first three participants in Innovation Lab for Museums (see sidebar, p. 52) have chosen to tackle a variety of challenges arising from their changing environment.

The Levine Museum of the New South (LMNS) is exploring how history museums, working together, can tackle an important contemporary issue facing their communities. Director Emily Zimmern reports that after working with their project partners, the Atlanta History Center and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, in the first few months of the Lab, it became clear to the group that “what is really innovative about our project is the learning network- the learning itself.” So their initial innovation isn’t so much about the end result addressing Latino immigration in the New South-it’s about how to work on this with other institutions in order to implement new approaches. This means changing the museum’s organizational culture and traditional way of doing things, potentially helping others do the same.

For Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA), innovation means challenging traditional youth arts education models that typically encourage youth to become working artists or arts administrators. YBCA wants to help young people become creative thinkers and agents of social change. Like LMNS, they expect to create a program that can be replicated at other institutions, perhaps even transforming youth arts education nationally.

At the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (NAMA), staff aspire to change the very nature of the museum’s relationship with its visitors. Director of Education Judy Koke says that while museums tend to view visits as discrete entities, visitors see their visit “as part of the larger fabric of their lives.” The museum would like to gain a better understanding of how museum-goers’ visits and their relationship with art extend into their everyday lives, she says. NAMA has been experimenting with interactive, participatory elements in temporary exhibits that begin to address this challenge, but Koke says they will need transformative change for their permanent exhibits, visitor services and overall museum operations.

Overcoming barriers to innovation

What forces conspire to make museums bad at change? Lack of time, for one, suggest Koke. Innovation takes time, mental energy and space. But in museums “people are usually doing more than one job and running at 100 miles an hour, which doesn’t support innovation,” she says. Participating in the Lab forces museums to commit key people’s time to the process. The Lab also provides distance and space through a week-long, off-site retreat for the teams of all participating museums.

How can you create this kind of mental energy and space at your museum? For starters, you might schedule your own mini-retreats: days or half-days at an off-site location where the only assignment is to brainstorm and dream, to come up with the “half-baked” ideas that could turn into promising innovations. Once you find an idea you want to develop further, write your innovation project into the museum’s annual plan, both for the organization as a whole and for individual staff.

Giving innovation this kind of official status can help ensure it doesn’t get shoved aside by “business as usual” and reassures people that they will be assessed and rewarded for their participation. And you have to make it clear, as Koke puts it, that there is explicit “permission to fail.” Innovation entails risk, and punishing failure that arises from trying good ideas will ensure that no one in your organization advances such an idea again!

Money can help, of course, but people might be afraid to spend it. “It’s scary to think about applying scarce resources to something you are not sure is going to work,” notes Koke. The Lab helps ease this fear by providing $40,000 dollars to each participating museum to fund prototyping and implementation. This “found money” frees people’s thinking by giving them permission to take chances. After all, it’s not money that was going to fund something else! corporations and museums create this financial safe space by devoting a small portion of the budget each year to what is variously called research and development, innovation or experimentation. In a small museum, this might just be $500, but its effect could be out of proportion to the amount.

While time and money are both concrete practical concerns, we hear from applicants to and participants in the Lab that the biggest barrier to innovation is our own attitudes, mental habits and institutional culture-what Joel Tan, director of community engagement at the YBCA, calls museum “habitus.” He asks, “What does it mean that lots more people are accessing arts and culture and ideas in a decentralized way—through the Internet, through a culture of interactivity?” As the public moves away from centralized expertise and curatorship, new needs arise. “Perhaps the innovation we need most is about setting a framework for lots more people to participate in arts and culture,” he says. “This starts with changing the attitude of the people in our field.”

Another obstacle to change is satisfaction with the status quo. “The biggest barrier to innovation is complacency-being content with your success,” says the Levine Museum’s Zimmern. “It’s even harder for institutions that have enjoyed some degree of success to challenge their assumptions,” asking “‘Where do we need to be thinking differently? Just because it’s working now, will it work in the future?”‘

One way to combat complacency is realizing that what works now may not work in the future. For YBCA, says Tan, this means understanding that “young people expect to get different things out of life. The traditional career trajectory is disrupted by the declining economy, wildly shifting demographics and advances in technology. People are getting older, living longer, working more. It’s an entirely different world.”

If complacency is a barrier to change at your organization, try sharing CFM’s weekly e-newsletter, “Dispatches from the Future of Museums”; forecasting reports such as TrendsWatch 2012; and guides to creating stories of the future, such as Tomorrow in the Golden State: Museums and the Future of California.

Changing institutional culture requires not only difficult conversations, discipline and focus but playfulness and a certain license to dream. To foster these conditions, it helps to have a facilitator-a skilled, experienced outside party with no stake in the outcome. Each museum participating in the Lab works with a process facilitator provided by EmcArts to mold their “half-baked” idea into a viable new way forward. The first museums participating in the Lab have already found this to be tremendously useful. Koke notes that their facilitator “encourages us to look at models outside of museums and helps us to question our assumptions.” Tan appreciates having someone “remind us not to move right into the tactical, to be intuitive about the nature of innovation.” Facilitation can increase clarity, says Zimmern, encouraging “crisper and clearer” thinking.

Museums can foster innovation processes by recruiting their own facilitators. If you haven’t the budget for a trained consultant, ask board members who could offer connections to independent professional facilitators or provide volunteer services from their own staff.

What’s next?

The innovation teams from all three museums participated in a week-long “intensive retreat” in Air lie, Va., this May. There, they worked with their facilitators, traded notes and shared experiences with the other teams. Stay tuned.

How does the Innovation Lab for Museums Work?

The lab experience consists of four phases spread out over a period of up to two years.

Phase 1: A four-month period of counseling between an EmcArts facilitator and organizational leaders explores and clarifies the new project, strengthens the organization’s Innovation Team and builds momentum for the intensive retreat and subsequent prototyping.

Phase 2: A five-day residential retreat brings together the innovation teams for each of the three participating museums to catalyze implementation of the museums’ strategies.

Phase 3: Six months of implementation coaching and facilitation by EmcArts supports innovation prototyping and tryout of activities in low-stakes environments. Innovation Lab for Museums provides participants with $40,000 toward project prototyping.

Phase 4: Dissemination. Participants disseminate their experiences broadly by presenting at conferences and other venues; AAM and EmcArts synthesize and share lessons learned.

Generous support from MetLife Foundation has provided funding for two rounds of the Innovation Lab for Museums, with three museums participating in each round. Participants in the second round of Innovation Lab for Museums will be announced in July. Watch AAM communications outlets for news of future calls for proposals.