This article originally appeared in the March/April 2013 edition of Museum magazine.

When the digital age transitioned into the 21st century, the coupling of incredible advancements in interactive technologies with the global exchange of ideas encouraged a system in which comprehensive access to information has become the new paradigm in public presentation and scientific analysis. Natural history collections hold vast amounts of knowledge capital, yet due to the generally perishable nature of many museum collections, geographic distance or inadequate funding, they are often not universally accessible. Through the creation of virtual repositories complete with built-in analytical tools, natural heritage institutions can develop methods for safely distributing this wealth of information in order to service an ever-increasing need for access and, ultimately, to stay relevant in this dynamic and rapidly expanding information age.

While many museums are now making efforts in 3D visualization, virtual collections and integrated database management presentations, the Idaho Museum of Natural History (IMNH) is taking this further by putting entire collections online in virtual repositories. We call this “democratizing science,” or simply put, migrating repositories of things into formats where they are put back into the hands of those for whom all repositories hold their collections: the public and scholar. The goal of the Democratization of Science Project is to use 3D technologies to make entire collections, or entire museums, available so that any student, any child, any scientist or any enthusiast, anywhere in the world, can do their own analyses and exploration.

We see this as the future of museum repositories and as a critical means to maintain the relevance of museum collections for the future. We suspect that important scientific and educational advancements are often not made, or critical connections are missed or overlooked, simply because people do not have access to complete collections or to the often unpublished data connected to them. We hope to change this by democratizing access through virtualization. We have not only developed the model for how this should be done, we have already implemented the first examples.

This project began rather simply. In 2006 I was leading a large, interdisciplinary biocomplexity project on Sanak Island, one of the eastern Aleutian Islands off the coast of Alaska. One of the primary goals of that project was to use animal bones from ancient village sites to reconstruct the environmental history of the north Pacific. I was working with zooarchaeologist Matt Betts, who is now the curator of Atlantic Provinces Archaeology at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Quebec. As the samples were excavated, a troubling question arose: Was there a vertebrate comparative collection anywhere that had the specimens necessary to identify the bones from what appeared to be nearly 200 taxa of mammals, birds, and fish, plus age and sex differences? We would need to identify nearly 200,000 bones and did not know where we would be able to do this.

On returning to Idaho State University that fall, I was assigned the directorship of the Idaho Virtualization Laboratory (IVL), which is now a research unit of the Idaho Museum of Natural History. The facility had begun like many virtualization labs, with the goal of scanning a few interesting artifacts, bones or other items and providing online access to the 3D representations. But Betts and I saw an entirely new potential for this unit. Recognizing that the problems we had analyzing the bones from Sanak Island were problems faced by archaeologists, osteologists and ecologists across the Arctic, we formed a collaboration with database specialist Corey Schou of the Idaho State University Informatics Research Institute. We proposed to the Office of Polar Programs at the National Science Foundation (NSF) that we create a virtual 3D library of vertebrate collections so that anyone could conduct these types of studies without access to the few, and often proprietary, research collections. The result was the Virtual Zooarchaeology of the Arctic Project (VZAP). With the support of two NSF awards totaling Sr.s million, we put 3D and 2D images of every bone from most arctic mammals, birds and fish online in a taxonomically ordered and hierarchically structured database.

Currently, there are dozens of projects funded throughout the Arctic, where a comprehensive comparative vertebrate osteology collection is critical for success. Yet only a few of these exist in North America. VZAP solved this problem by creating a virtual repository of northern osteology accessible from anywhere on the planet. As of this writing, we have scanned more than 200 specimens from nearly 150 different taxa. The site is currently being used by hundreds of scholars, students and members of the public from around the world. As a result of this project’s success, we entered an agreement with the Smithsonian Institution to begin scanning whale skeletons for worldwide identification efforts, and just recently we put the first 3D scan of a complete Orca Orcinus online.

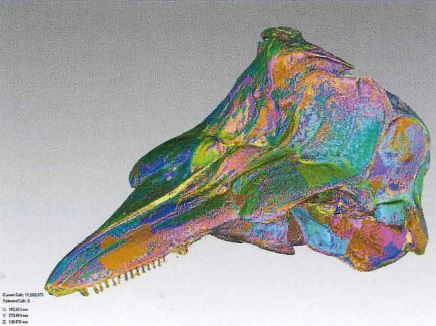

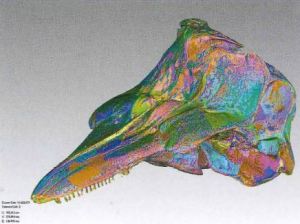

This radical shift in how material data are managed and made available required new developments in three areas. The first was in 3D virtualization. After many years of digitization, we have become very good at this with accuracy approaching +/- .005 mm, and we have developed new rendering techniques that bridge science and fine-art aesthetics without loss of accuracy or resolution. The second is hyper-plastic database design. This means that the database is so flexible that any type of data can be added without restructuring. In conjunction, we have created and are continuing to develop new techniques of database image storage. We currently offer more than 40,000 high-resolution images with real-time resolution enhancement while still maintaining integration with the parent database structure, and provide nearly 6,000 3D models. Third, these two structures are integrated with on-screen measurement tools that allow the creation of quantitative data from any computer monitor anywhere in the world; these tools have been tested and shown to be accurate to approximately .005 mm.

The scanning process is time intensive, but we have a suite of scanning technologies available in the IVL. We did much of our early work with the Cyberware MS and M15 scanners, and over the last three years, the Konica Minolta 9i has been the workhorse of the laboratory. While we continue to use these scanners, we have now incorporated two new Faro Edge arm scanners for detailed work, and a Faro Focus 3D for scanning large whale bones, buildings,

museum displays, and rock art panels and other archaeological sites. All of our scans are processed in Geomagic Studio, which is a key element of the production sequence.

After scanning, every item is photographed at a minimum of 16 megapixels, and then a combination of Zbrush and Photoshop is employed to overlay or “texture” the photographs onto the original scans. This creates a photo-realistic 3D model that looks identical to the original, or what we refer to as “archival digital surrogates” as true to form of the original object as current technologies will allow. This has been so successful that we are now doing specific requests and contracts for museums, research projects, and agencies.

When I became director of the IMNH in 2010, I brought this model of science to the museum. But instead of shipping samples from around the continent to Idaho for scanning, we started on the next phase in our drive towards making natural history collections available worldwide by creating The Virtual Museum of Idaho project. Here again, it is not about putting a sample of objects online, nor is it an attempt to make one photo of every item in the museum catalog available. This is not the typical virtual museum of the last 10 years, but rather a set of virtual repositories that provide the foundation for innumerable virtual museums, exhibits and education modules.

Following the model proposed here, complete collections of everything from Helicoprion shark fossils, to Bison latifrons bones, to stone tools from key archaeological sites, to baskets from the ethnographic collection, to the entire IMNH herbarium; all will be scanned and put online as virtual repositories with on-screen tools so that they can be studied, measured and analyzed by anyone with an interest to do so. With a generous grant from a private foundation that sees this project as transforming scientific democratization and collaboration through accessibility, we intend to make the bulk of the IMNH collection available over the next five years. As new collections are added, we publicize them on Facebook, through our website, on specialized science blogs, and through scientific publications.

For the IMNH, the democratization of science is about using online media to make local, often inaccessible collections part of the world’s scientific agenda, and allowing distant, often isolated individuals, classrooms or collaborators the opportunity to conduct their own investigations of museum collections from wherever they may be located. This is critical to the mission of the IMNH. Idaho is largely rural and most of the state cannot easily come to the museum, thus we are providing universal access online.

But there is a larger advantage to this model. Many local and regional museums have specific and spectacular collections that are critical to the global scientific agenda, yet are underutilized because of distance or because the scientific community does not know they exist. This model allows museums to make scientific analysis of their collections possible on a global scale, and to highlight the importance of those collections to their communities. To help other museums that might want to pursue this approach, we are actively seeking collaborations, and will also hold workshops and training programs.

This should be the museum model for the century, and it will drive collections use and publication, and firmly establish and maintain the relevance of natural history museums as key sources of science and enlightenment.