| Rob Walker |

The theme for this year’s annual meeting is Storytelling, and we’ve recruited Rob Walker, co-designer of the Significant Objects project, as a thought leader to help us explore how stories add tangible value to the objects they are connected to. You can join me on Tuesday, May 21 from 10:15 – 11:30 am for a conversation with Rob about Significant Objects. I invited him to share a bit about the project here on the blog, both to prime us for the meeting, and to share a bit about his work with those who won’t be able to join us in Baltimore.

Every object has a story, right? Actually, I’d argue that’s a bit limiting: Every object has multiple stories. We know the significance of a thing is often linked to its provenance — who made it, out of what, when, and where. But ownership stories matter, too. In fact, who owned and used a thing can completely alter our perception of it. A mass-produced doodad suddenly becomes much more interesting to scrutinize when we learn it was once the property of Andy Warhol, Margaret Thatcher, or Billy the Kid. Ownership stories also come in very personal varieties. The trunk in my home office will never be displayed in a museum, but it means quite a lot to me because it belonged to my father, and his father. The trunk’s connection to my own life story is what makes it a significant.

Thinking about all this led to an experiment that I was involved in with writer and editor Joshua Glenn. We set out to explore another variety of object story: the conjectural, speculative, imagined and outright fictitious. Our hypothesis: Narrative can be such a profound driver of meaning that even an openly false story could add value — measurable value — to an object.

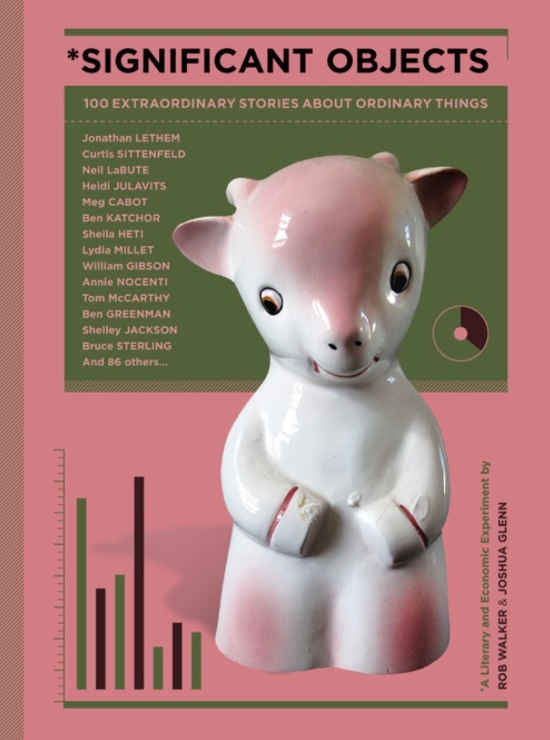

The original Significant Objects experiment involved 100 deliberately low-value, basically meaningless, profoundly insignificant doodads, rounded up from thrift stores, yard sales, and flea markets, at a total cost of $128.74. We recruited 100 writers and storytellers — from best-sellers such as William Gibson and Meg Cabot to literary up-and-comers to television writers, comedians, cartoonists and anyone we believed had an interesting imagination. Each invented a tale concerning one item from our menagerie of ashtrays, coffee mugs, piggy banks, figurines, and the like. Finally, object and story were paired on eBay, with the original thrift-store price as the minimum bid. (It’s important to note that this was not a hoax or other attempt to mislead: Every listing included a prominent notice explaining that “the significance of this object has been invented” by the relevant author, along with a link back to our site for full details.)

The results: Our stuff sold for $3,612.51 — a whopping “significance premium” of just 2,700%. Every single object sold for more than we’d paid; the top price was $192, the average $36. (The money went to the writers.)

Why did this work? Of the many possible answers to that question, I think there’s one worth zeroing in on here, partly because it involves a development we did not anticipate: The project itself became a kind of story, one that people not only wanted to enjoy, but to shape. We had assumed it would be an enormous challenge, for instance, to persuade writers to participate in this scheme. We were surprised when those we solicited said yes — but outright startled when people began approaching us, volunteering to take a crack at making some bit of yard sale detritus “significant.”

Meanwhile, buyers were sending us pictures of Significant Objects in their new homes, or anecdotes about toting the things to readings by our contributing writers. We realized that on some level owning one of our objects was like buying a souvenir of our experiment. In retrospect this makes perfect sense: A visitor’s inquiry about some tacky statuette in the living room would prompt a pretty great story, after all.

|

| Significant Objects at MOMA Post on HiLoBrow |

Thus we learned that the project had taken on a life of its own — and kept going. We bought more objects, recruited more writers, and converted our operation into a fund-raiser, donating thousands of dollars to nonprofits like 826 National and Girls Write Now. Ultimately publishing more than 220 stories, we played with variations on our theme — selling a “mystery object,” or having three writers invent stories about identical objects, or presenting a multi-object story over several days. We organized an “object slam” as part of San Francisco’s Litquake festival, where audience members invented competing stories about a single thing. I helped organize an event at the Museum of Modern Art, titled The Language of Objects, that involved some of our contributors and other friends responding imaginatively to the museum’s “Talk to Me” exhibition, which concerned human-object communication.

Most recently, when Fantagraphics published a book collecting 100 of the project’s finest pieces, the public radio program Studio 360 invited its listeners to invent stories about three objects that host Kurt Andersen and I picked from a New York City thrift store. There were more than 300 entries.

The lesson in all this for us was that the speculative form of story we’d set out to explore offered a different form of engagement. Imagination led to participation; boundaries got blurred, and our objects turned out not to be an end point, but a starting point.

As a result I’ve paid closer attention to other experiments, by museums and others, to open up the notion of objects as communicative prompts that invite audience involvement. One interesting example is the Object Ethnography Project, which involves trading objects for stories; through a series of exchanges, each thing acquires up to three distinct narratives. Our friend Paul Lukas, a New York-based writer and overseer of various creative projects, has hosted a series of “Show & Tell” events, which invite attendees to tell a personal story about an object they’ve brought along. Most recently, The Museum of Contemporary Craft, in Portland, has supplemented its exhibition “Object Focus: The Bowl” with a Tumblr dedicated to stories about bowls. Some are commissioned, but many come from the general public, submitting a variety of tales and even poems.

What matters here is that in all cases, stories are both an end and a means. Significant Objects resulted in an impressive outpouring of narrative creativity, and the book version stands not only as a document of the project, but also a tour de force of imaginative thinking inspired by objects – it’s amazing to experience the range of strategies our writers employed to make readers re-consider these previously overlooked things. In other words, the stories could stand on their own.

But the pleasant surprise (and noteworthy takeaway) was that the stories helped make the original experiment something people wanted to be a part of, not just observe. That’s what gave Significant Objects a life beyond what we ever could have imagined — and gave us a pretty good story to tell in the bargain.

What an amazing project! I look forward to hearing more in Baltimore.

I loved this project when I first heard about it–as soon as I read about it, I said it's so "Social Life of Things" by Arjun Appadurai! That text, and others like it were central to my own training as a material anthropologist, and projects like "Significant Objects" only underline why objects are so important to human storytelling and human meaning.

One question–why do you think that the discipline of material anthropology hasn't really caught on in American training? There's "material culture studies" in folklore and American Studies departments, but they don't typically take this object-centered approach, nor do they approach objects (especially items like trash, mass produced objects, etc.) with this same theoretical approach. I've always found this lack of object-centered thinking in the US curious (I'm American, by the way).

Hope that you'll post some kind of follow up on Rob Walker's talk for those of us that won't be present for it!

Thanks for sharing.

We have been taking comparatively meaningless objects from thrift and gift shop, creating tongue-in-cheek/bogus provenances for them, and selling them at fundraising auctions at the annual conferences of the Mountain Plains Museums Association since 2001. Our first such item, a white elephant figurine, was purchased by Ed Able for $100. They have raised as much as $300 per auction for the association and have included everything from a Homer Simpson action figure to a ball and chain (which reportedly belonged to Bugs Bunny and may have been from his "Kill the Wabbit" period).

Steve Friesen,

Interestingly, perhaps, we explicitly ruled out a charitable/fundraising dimension in our initial experiment — we suspected that introducing the idea of a "good cause" would get in the way of measuring story value.

Once the experiment was done and we kept publishing stories, we DID a fundraising angle, funneling money to nonprofits. And indeed, prices rose!

I would imagine this factor would be even more important in the context of a live fundraising auction — everyone is there basically to make or consider making a donation, so the incentive to bid is high. What you've done is a really interesting comment about charitable auctions, actually, and what motivates bidders.

As a side note, I must say your objects sound way cooler than ours!

Rob

Fascinating! The Museum of Broken Relationships also makes clear to participants the pleasant and painful ways that everyday objects accrue meaning with backstory. http://brokenships.com/

Rob,

The ball and chain was quite cool and I can tell you the back story on that in Baltimore (I'll be helping at the MPMA booth) but the vision was similar yours, to transform the ordinary into more by creative use of ideas and language. Some of us are part of ongoing conversations about the sacredness of objects, a sacredness derived from provenance. How do we know if it's a "piece of the true cross" without the story behind it? And similarly, invented stories can create false sacredness, a pitfall for museums seeking authenticity.