This article originally appeared in the May/June 2013 edition of the Museum Magazine.

This center of heaven,

This core of the earth,

This heart of the world,

Fenced round with snow,

The headland of all rivers,

Where the mountains are high and

The land is pure.

This center of heaven,

With its ecological wholeness, stark beauty and sense of unfettered freedom, the Chang Tang is a place where mind and body can travel, where one’s soul can dance.

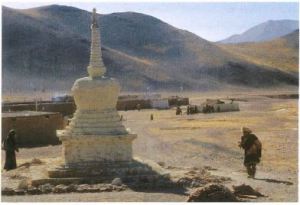

The World’s Second Largest Protected Reserve

A harsh, windswept landscape, remote and desolate, stretches across the northern part of the Tibetan Plateau in China. It is called the Chang Tang, the “northern plain,” in Tibetan. It is 600 miles at its longest and 300 miles at its widest. It is the second largest protected reserve in the world, exceeded only by Greenland National Park. Much of this gaunt terrain lies 14,000 to 15,000 feet above sea level, and its northern part is 16,000 to 17,000 feet high. Though austere, the Chang Tang has a tranquil beauty, its wild emptiness alluring with a sense of the unknown. The plains roll silently on, horizon giving way to horizon, broken by turquoise lakes and ice ranges with some peaks over 20,000 feet high. At this elevation, the vegetation is scant, grasses, forbs (herbaceous plants) and shrubs no more than a foot high. The climate is severe, to -40 degrees Fahrenheit (-40 Celsius) in winter. Snow falls even at the height of summer.

An alpine steppe covers the southern part of the Chang Tang, and with more precipitation here, alpine meadow extends over the eastern part. Here Tibetan nomads live with their yaks, sheep, goats and horses. The high northern area is desert steppe with the ground mostly bare, the scattered grass tufts too few to support livestock. In November and December 2006, a team of Tibetans, Han Chinese and I drove cross-country west to east for 1,000 miles, a distance equivalent to that from New York to Chicago, and we did not see a single person. Yet there was a fair amount of wildlife, including Tibetan antelope or chiru, and wild yak. What a glorious experience! Where else in the world can one find its equal? The spirit exults that a wild place like this still exists.

With great foresight, the government of the People’s Republic of China established the Chang Tang Nature Reserve in the Tibet Autonomous Region in 1993. At 115,000 square miles, it is the size of New Mexico or Italy. Other reserves border it in neighboring Xinjiang and Qinghai provinces, and together these offer a measure of protection to a Chang Tang area larger than California. Adjoining it to the east and extending beyond the Chang Tang is the

58,000-square-mile Sanjiangyuan Reserve created to protect the headwaters of China’s great rivers- the Yellow, Yangtze and Mekong-upon which the lives of millions of people in the lowlands depend. This vast protected region, still little known, represents one of the great natural treasures of China and the world. People live within the reserves in Tibet and Qinghai. The challenge is to manage the reserves in such a way that the wildlife, rangelands, and communities all flourish. The conflicting demands of conservation, economic development and the welfare of an indigenous culture need equal attention.

The Riches Of The Chang Tang

At first glance, the Chang Tang may seem barren, but it has a rich flora and fauna that have evolved in these harsh conditions. More than 300 species of flowering plants grow here, grasses and legumes and composites, as well as gentians, potentillas, asters, and many others. A bird list may reach 100 species, from black-necked cranes and bar-headed geese to sacker falcons, ravens, snow finches and horned larks. The mammals comprise a unique assemblage, one that first brought me to the Chang Tang. There is the chiru, the Tibetan antelope, whose migrations define the ecosystem. The wild yak, the rare and huge ancestor of the domestic yak, is to me the symbol of these remote uplands. The russet-colored Tibetan wild ass or kiang is widespread on good pastures; it is a curious creature that at times gallops parallel to passing vehicles. Others include the blue sheep-actually related to the goat-in rugged terrain, the graceful Tibetan gazelle, the Tibetan argali sheep with its massive curled horns and, in the east, scattered herds of white-lipped deer. Preying on these ungulates are the wolf, snow leopard and lynx. Newborns fall prey at times to red fox, Tibetan sand fox and Tibetan brown bear. All these predators also hunt the small plateau pika, which is locally abundant and remains active around its burrows all year.

To study this diverse mammal community and to promote its protection has drawn me back to the Chang Tang every year for more than a quarter century. Even to locate the mysterious calving grounds to which chiru females migrate as far as 200 miles in the most desolate and uninhabited terrain requires a major expedition.

No wildlife population remains static. A heavy snowstorm may starve thousands of animals, domestic as well as wild, as I witnessed in October 1985. Commercial hunting greatly reduced wild populations in the 1990s, but with better protection, numbers in some areas are again increasing. But greater numbers of some species such as kiang and bear create human-wildlife conflict. And as the nomad culture changes with improvements in economic conditions, attitudes toward and tolerance of wildlife change, too. Conservation is not a goal measured in a limited project but is a never-ending process to which my Chinese co-workers and I have dedicated ourselves and to which we have to adapt continually.expedition.

The Chang Tang Reserve is contiguous with the West Kunlun, Mid-Kunlun, and Arjin Shan reserves in Xinjiang, and with the Kekexili Reserve in Qinghai. The Chang Tang Reserve is thus not just a limited protected area or national park, but together with the other reserves represents a whole landscape, an ecosystem in which all species of plants and animals can continue to seek their destiny. Climate change will affect or is already affe cting all protected areas. As habitats shift or are modifi.ed, species can adapt, move or die. The Chang Tang ecosystem is large and varied enough that species can accommodate themselves to changes, if properly managed. Smaller reserves, by contrast, will be able to survive only by establishing one or more strictly protected core areas, such as national parks, surrounded by a landscape managed to assure the livelihood of people as well as all other species, and with core areas connected by corridors of habitat through which species can move from one area to another.

We know that the Chang Tang’s riches are not measured in oil and gold-though both occur there-but in its spacious vistas, cushions of flowers, vibrant chiru herds and distinctive pastoral culture. All these must remain a gift to the future.

Do if you like that which may seem sinful

But help living beings,

Because that is truly pious work.

-The last words of Tibetan hermit saint Milarepa (1052-1135)

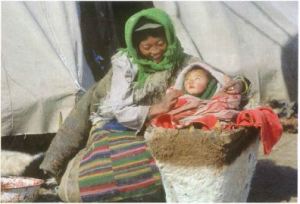

The Pastoralists Past And Present

Tibetan nomads, best referred to as pastoralists, evoke the romantic illusion that they have always been free to roam with their livestock in search of their destiny. Not so. For centuries pastoralists were bound by heredity to an area controlled by a monastery or an aristocratic family to whom they paid annual taxes in butter, wool and meat. Tibet’s old society came to an end in 1959, and a decade later, with the onset of China’s Cultural Revolution, private property was abolished and cooperatives were established. These were disbanded in 1981 after causing extreme hardship. Property including livestock was then redistributed equally to families, and areas were divided into administrative units or xiang within which households had grazing rights.

Historically, pastures were reallocated every three years. Their size depended on the number of livestock. This important practice was discontinued in 1959 with the result that many pastures were seriously overgrazed, especially since the government promoted livestock expansion. Then, in the 1990s, the government again changed grazing policy. Each family was given a parcel of land with a lease of 30 to 70 years, depending on the area, to which the family was confined. Because the human population has increased greatly in recent decades, there was not enough land to give a sizable plot to everyone, and some families received too little to support themselves. Nomads had now become small-time ranchers. During a drought or heavy snow the livestock could not usually be moved elsewhere to better grazing. As a result, pastures became ever more degraded, a trend accelerated by climate change, which has brought more frequent and more violent sandstorms and changes in precipitation.

Since the pastoralists now “owned” land, they wanted to fence it, just as settlers did in North America and Australia. Fences, subsidized by the government, keep stray livestock out-and wildlife, too-and the owner’s livestock confined without the need to herd it. And this places ever greater stress on the fragile pastures. As Sangjie, a nomad, told me, “The largest problem we face is changes in ourselves.”

The pastoralists began to settle down in the late 1980s. The traditional yak-hair tents have mostly now given way

to mud-brick houses. As economic conditions improved, families bought motorcycles to replace horses. Today houses, and even tents, may have solar panels and satellite dishes to run television sets and electric blenders to mix the traditional butter tea. New roads permit trucks to deliver grain and other necessities to remote households and to buy wool, butter and hides. This has eliminated the ancient trading caravans.

I have witnessed these rapid changes. Tibetan pastoralists adapted to live in one of the world’s harshest environments, and they remain resilient even in the face of recent political changes. They are hospitable and generous and concerned about the land and their future. I admire them greatly.

The Endangered Chiru

We walked for a week in 1997 across the steppe in western Qinghai province. The rangeland was in good condition and people were few, but we looked for wildlife in vain. The chiru, yak, kiang and others had been slaughtered by local people and outsiders to “become rich,” as one Tibetan explained. As we studied wildlife in the Chang Tang during the 1990s, we observed the past die as the wild herds were butchered to feed laborers in town and to make a quick profit. The chiru suffered the most. Trapped by pastoralists and gunned down by motorized teams from the towns, tens of thousands were slaughtered for their wool, the finest of any species. Smuggled to Kashmir in India, the wool was there woven into soft, luxurious shahtoosh, a product that is much in demand as a fashion statement by the world’s wealthy. A beautifully embroidered shawl may sell for $15,000.

The horns of the chiru are widely used in traditional medicine and find a ready market in Lhasa and Beijing. Although

the trade is wholly illegal, I estimate that as many as 250,000 to 300,000 chiru were killed during the 1990s. Better protection in China and enforcement of wildlife trade laws in other countries have greatly reduced the carnage. Indeed, our surveys show that some chiru populations are increasing in number, protected by local officials and communities. Perhaps someday the chiru can be harvested in a sustainable manner for their meat and wool to benefit Tibetan communities. Good science and good laws are essential for conversation-but are not enough. To achieve success, local communities must be involved. They must be partners in any endeavor, contributing their knowledge, insights and skills, as well as their moral values.

The Challenges Of The Chang Tang

About a decade ago, the government confiscated guns from the local population, something that greatly benefited wildlife. However, protection may create new problems, as two examples illustrate. Kiang has become so abundant in some places that pastoralists complain about competition with their livestock for grass. Brown bears used to be shot when they killed livestock or entered an isolated tent. In the past few years, they have learned that houses are safe and offer free meals of butter, flour, and meat. When no one is home, a bear smashes windows, doors or even the wall to ransack the rooms. In some areas, bears are raising such havoc that people are losing patience. We have to work with communities and government to help resolve such problems through research, education, imaginative joint solutions, and better wildlife and livestock management policies.

Then there is the problem of the pikas, an essential link in the food chain of the Change Tang. Weighing only 4 to 6 ounces, these tiny relatives of rabbits can become extremely abundant. Pastoralists and officials despise pikas because the perception is that they compete heavily with livestock for forage and destroy pastures. As a result, they have been mass-poisoned in an eradication program covering over 80,000 square miles. But do they really damage rangelands? Research shows that pikas become most abundant on degraded pastures, just as prairie dogs do in North America. Their digging brings minerals to the surface, making plants more nutritious and diverse around burrows. Soil loosened by pikas holds water better and promotes plant growth, again a benefit to livestock. Pikas eat some poisonous plants that can kill sheep or goats. Snow finches nest inside old burrows, and the whole predator guild from weasel to bear to golden eagle preys on pikas. These and other benefits are of immense value to the whole ecological community of the Chang Tang. Animals are a tangle of fact, cultural ideas and illusions. We are trying to change perceptions through community meetings and with a booklet on the importance of pikas, written in Tibetan for adults and schoolchildren alike.

Three points have to be considered. One is that problems are local and must be solved locally. A second point is that no single approach may offer universal solutions. And a third point is that all such problems are biologically and culturally so complex that they require a long-term integrated approach. There is as yet no wildlife management on the Tibetan Plateau, not even in the reserves. Animals are either fully protected or completely unprotected. There is no policy to resolve human-wildlife conflict, nor one to manage species in a rational and sustainable manner.

Presently, we address problems on a case-by-case basis. Pastoralists are fencing the critical winter pastures to save the grass for their livestock. Fences hinder movement of wildlife, and kiang, chiru and gazelle sometimes die when they become entangled in the wire. We are working with communities to design fences that cause the least amount of hindrance, and we are trying various methods of bear-proofing homes.

Spiritual Values And The Future Of The Chang Tang

There is now, in general, a much greater awareness of the value of wildlife and a healthy habitat on the Tibetan Plateau than there was even two decades ago. Among the governmental organizations involved in studying and protecting the Chang Tang and other reserves are the State Forestry Administration, the State Environmental Protection Agency, the forestry departments of Tibet, Qinghai, and Xinjiang, the Institute of Zoology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Northwest Plateau Institute of Biology, the Tibet Academy of Agricultural and Animal Sciences, and the Tibet Plateau Institute of Biology. Non-governmental conservation organizations are also making valuable contributions, including the Snowland Great Rivers Environmental Protection Association, Green River, Shan Shui Conservation Center, World Wildlife Fund, and Wildlife Conservation Society. Some Tibetan communities themselves are beginning to maintain the ecological integrity of their land. To give one example, the community of Cuochi in Qinghai banned hunting because of the belief that the deities of the nearby holy mountain Morvudan Zha will punish the people if they kill wildlife. The community now prohibits livestock grazing on one small mountain range to protect wild yak, provides rangeland where chiru can feed unmolested in winter and monitors wildlife populations.

Preliminary management plans have been prepared for the Chang Tang and some other reserves. Both the national and local governments provide funds, though not enough, to maintain a guard force, conduct wildlife surveys, regulate livestock numbers and develop other management initiatives. But since ultimately the local communities will determine the fate of wildlife and rangelands, conservation organizations have initiated education programs, organized village patrols to deter outsiders from poaching and have encouraged an attitude of caring for the environment and ultimately the region’s own future.

Monasteries have sacred lands where hunting is forbidden. We have been working with monks to show them how to monitor and record wildlife, and also to encourage the communities near them to live by the basic Buddhist principles of respect, love, and compassion for all living beings. We hope that with ecological insight and religious conviction local communities will realize that their livelihood depends on treating their land with understanding and restraint. To that end, we also encourage festivals presided over by a revered lama (Tibetan Buddhist monk) who speaks about the importance of people, livestock, and wildlife living together in harmony. There is dancing and horse-racing, and then everyone ascends the lower slopes of the holy mountain (each community has one). There the lama blesses the land and all life as an eternal gift to the future.

George B. Schaller, Ph.D., is a biologist and senior conservationist for the Wildlife Conservation Society, vice president of Panthera, and adjunct professor with the Center of Nature and Society at Peking University in China. He is the author of 16 books, including Tibet Wild: A Naturalist’s Journeys on the Roof of the World.

Donate funds to concerned nonprofit organizations.

If you visit the Tibetan Plateau, inquire about progress in conservation. This alerts officials that there is worldwide interest in the Chang Tang.

Comments