This article originally appeared in the July/August 2013 edition of Museum magazine.

Managed landscapes at museums enhance the visitor experience.

When visitors step into an urban museum with its front door just off the sidewalk or at the terminus of a long flight of stairs, they are immersed in a human-made environment of architectural spaces and creative strivings. These surroundings can be quite beautiful, but a significant element is often missing: the human connection to the natural world.

In contrast, consider what arriving visitors see at the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA), where the museum’s focus on green initiatives extends even to the parking lot. Here, tall grasses evoke the indigenous Midwestern prairie and an earth berm obscures the adjoining busy road. Fine Gardening magazine blogger Billy Goodnick raved in a posting that he was left “wondering about the kind of institution that devotes this level of design and care to the place where visitors leave their cars. The obvious answer is that, to the museum, beauty, in all its forms, is a priority.” Indeed, explained Mark Zelonis, the museum’s Ruth Lilly Deputy Director of Environmental and Historic Preservation, “We are very fortunate to be an institution where the art of garden design and the craft of garden making and care are valued along with pictures hanging on a wall or sculptures mounted on pedestals.”

The IMA is not alone. All the landscapes surrounding museums have the potential to engage visitors, and many institutions have already seized this opportunity. This is true whether those landscapes are managed as parks, as public gardens or as components of a larger museum campus. Management is the key word here and refers to landscapes in which both living plants and hardscape elements are utilized to interpret and enhance natural environments. They serve as magnets to draw people together, to reduce social barriers and to allow for meaningful connections. While the objects within museum walls provide for static (though powerful) relationships, managed landscapes allow visitors to appreciate human creativity in a three-dimensional and ever-changing model that reflects their own temporal and calendar-based rhythms.

Rather than serving merely as a green backdrop or an engineered element to direct traffic flow, the well-conceived landscape can embody the museum’s subject. Visitors to Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia, for example, see not only Thomas Jefferson’s mansion, inventions, and preserved manuscripts, but also his gardens- those beloved botanical laboratories where he experimented with regional suitability and productivity of crops. Without experiencing his gardens, visitors to Monticello could not fully understand Jefferson, who, in an 1811 letter to Charles Willson Peale, said of himself, “Tho’ an old man, I am but a young gardener.”

Managed grounds can also provide a historical reference in a contemporary landscape setting. The gardens of the Getty Villa in Malibu, California-modeled after the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum-reinterpret the experience of ancient Roman culture, with appropriate plants, sculptures, fountains, and views.

Even in an urban environment, a museum can design landscapes to reference a more natural time and place. At the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C., “the grounds surrounding the building are considered an extension of the building and are a vital part of the museum as a whole,” explains the institution’s website. “By recalling the natural environment that existed prior to European contact, the museum’s landscape design embodies a theme that runs central to the NMAI-that of returning to a Native place.” The plantings represent the hardwood forest, wetlands and meadow ecosystems of the museum’s Mid-Atlantic setting, and plantings of corn, beans, squash, and tobacco reflect traditional ways in which Native people cultivated crops and managed land for their survival. Every summer, the museum releases ladybugs as a natural form of pest control-a popular event for visitors.

With managed approaches to their landscapes, many museums have already expanded their interpretation beyond the physical building and enhanced the visitor’s experience of the entire institution. The mission of the California

Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, for instance, is to explore, explain and protect the natural world. When visitors emerge onto the building’s roof, they encounter drifts of indigenous plants set among hummocks and valleys that mimic the local Mediterranean habitats.

Cogent cultural forces are currently shaping museum operations on many levels. These influences include the demand for a more democratic museum experience; heightened interest in the production and consumption of food; alliances with other institutions; and pressure to create sustainable, green initiatives. In response, progressive museums are looking to managed landscapes of all kinds to serve as vehicles for engaging visitors and meeting the needs of future audiences.

Democratizing the Experience

Many museums are recognizing the need to embrace our national transformation to a population that is wildly diverse, park-using, family-linked and not necessarily English speaking. In his 2009 Center for the Future of Museums lecture, “Towards a New Mainstream,” Gregory Rodriguez, founder and executive director of Zocalo Public Square, a nonprofit “ideas exchange” organization, called upon society and museums to “give up… role-playing,” and to understand that “them is us and us is them.”

Landscapes and plants can help institutions signal their accessibility through links to shared public spaces. In this way, museums gain visibility and the possibility of increased patronage by people who might otherwise never “cross the moat.” Fronting a museum on a heavily used public park, or creating an attractive public space where there was none, does not in itself solve the problem of declining attendance in an age of demographic change, but it can open the door to new expressions of identity and an exploration of nontraditional and possibly enlivening liaisons.

Providing a new entry point for potential visitors, the Philadelphia Museum of Art opened “Sol LeWitt: Lines in Four Directions in Flowers” in spring 2012. This outdoor exhibit features conceptual artist LeWitt’s work, comprising more than 7,000 plantings in strategically configured rows. Located on the hillside near the museum’s back entrance and next to its Anne d’Harnoncourt Sculpture Garden, the 18,850-square-foot exhibit is adjacent to the popular Schuylkill River Trail that attracts thousands of runners, walkers and cyclists every day. While the museum charges admission to its indoor exhibits, this exhibit is free and available to everyone.

Similarly, Charles Birnbaum, founder and president of the Cultural Landscape Foundation (CLF), an organization devoted to increasing people’s appreciation for cultural landscapes, wrote last year on the happy reconnection that architects Foster + Partners forged between the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Back Bay Fens parkland across the street. The famed 19th-century landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted had masterminded this section of marshland as a critical jewel in Boston’s Emerald Necklace; a 1,100-acre chain of parks linked by parkways and waterways. But decades of neglect had left the park heavily vandalized and trash-strewn. As Birnbaum reported in his March 2012 blog post on the CLF website, the new entrance coincides with an effort to completely restore the park and has inspired the museum’s director, Malcolm Rogers, to envision “a full restoration of the Fens, making it a potent urban recreational area.” Here, people can enjoy a series of brooks and ponds called the Muddy River as they “walk in a friendly environment buzzing with life—a great park in a great city.”

The Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) has also formed a strategic connection to a managed landscape belonging an unaffiliated entity. The Nichols Bridgeway arches over Monroe Street directly from its new Modern Wing to Millennium Park. In the park, the Piet Oudolf-designed Lurie Gardens anchor and animate the diverse elements of a large public cultural space that contains contemporary sculpture, a Frank Gehry-designed concert pavilion, an elaborate play fountain and temporary art installations.

Set in Stone, a report on the 1994-2008 museum and arts building boom by the University of Chicago Cultural Policy Center includes a case study of the AIC’s modern wing project. The document notes that the presence of the Bridgeway was paramount in securing keystone funding for the project, quoting AIC’s former board chair and donor John Nichols: “The driving concept for my wife and myself was connecting to Millennium Park.”

The hugely successful park, which draws a diverse mix of tourists and residents to the city’s center, is and will continue to be a real factor in the AIC’s ongoing efforts to build its attendance, according to Director of Public Affairs Erin Hogan. “Certainly the completion of Millennium Park was an important factor that shaped the Art Institute’s plans for the Modern Wing and beyond,” she explained in a recent e-mail. “Building a connection to the park was critical to the museum’s integration into Chicago’s lakefront, helped us secure gifts from donors and continues to bring new audiences to the museum.”

Planting the Garden and Setting the Table

Museums have become part of our national preoccupation with food. While celebrity cooks perform for television viewers, the medical establishment regularly issues bleak reports on the diet-related diseases that so many Americans have or will develop. This national eating problem has prompted responses from the pop-up food tent to the White House, along with innumerable books and movies about food, gardens and education initiatives.

Jessica Harris, an authority on the foodways of the African Diaspora, spoke at the 2011 “Feeding the Spirit: Museums, Food and Community” symposium organized by the Alliance’s Center for the Future of Museums and hosted by Pittsburgh’s Phipps Conservatory & Botanical Gardens. She noted that “food is the connector” and that “one of the few things the coming America will have in common is [a love of] food …. Food is cardinal.” For museums that have the physical wherewithal, youth and family programs that engage around plants and food are major attractors and bridge builders. Interactive exhibits, outdoor spaces, and programs focused on growing food are part of the solution set. Museums can use these features to leverage new programming and related marketing and thus act as social change agents mindful of the environment, public health and community building.

Chicago’s Jane Addams Hull-House Museum is one such success story. The museum’s revived tradition of “Soup Tuesdays,” started by social reformer Jane Addams in the early part of the last century, links the institution’s past with its present. “The Hull-House Settlement was historically a space for inquiry and social change, where both residents and neighbors engaged in direct action, advocacy, research, art making and community building,” explained Lisa Junkin, the museum’s interim director. “By offering our visitors free bowls of delicious soup, organic and locally sourced, we enact a form of radical hospitality that allows us all to participate in the delicious revolution.” Working with the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Centers for Cultural Understanding and Social Change, the museum’s kitchen work-along with an heirloom farming initiative-supports students and, as Junkin noted, makes “connections between biodiversity and cultural diversity.”

Another notable example of a museum engaged creatively with gardens and food is the Greensboro Children’s Museum in North Carolina, which has the first Edible Schoolyard (ESY) within a children’s museum setting. Founded 18 years ago in Berkeley, California, by author, chef and food pioneer Alice Waters, the Edible Schoolyard project provides online curriculum and annual training for educators to implement garden-based education in schools, communities and other child-serving organizations. The ESY at the Greensboro Children’s Museum allows kids and families to participate in all aspects of the farm-to-table experience via a hands-on organic teaching garden and kitchen classroom. It has become a prominent feature of museum activity, complete with classes, an ESY blog and broad-based community participation.

Plans for Chicago’s Navy Pier include a children’s museum and expansive plantings.

Creative Partnerships

A variety of alliances with other organizations can help drive special-interest landscape projects and increase museum attendance. In 2011, the Chicago Community Trust and the Chicago Botanic Garden invited small arts organizations and museums to a presentation on how to enhance their curb appeal, create a welcoming atmosphere and contribute to their neighborhood through the use of plants. The trust ultimately funded the pairing of students who had graduated from the garden’s design certificate program with five organizations, including the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art. The individual garden designers provided their sites with a needs analysis and a design plan, ranging from facade beautification with planters to full-scale garden installation with hardscape.

Such collaboration can serve mutual fundraising, artistic and educational goals. Kathryn Gilbert, who served as garden designer for the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art, explained that the learning experience was valuable to students who, as she described, were “put in a real-world setting, scheduling meetings, meeting deadlines and often interfacing with upper-level institutional administration but with the safety net of an industry professional as a mentor and advisor.”

Gilbert’s goal was “to extend the museum footprint with an outdoor green ‘living space’ to be enjoyed by visitors and members.” In her final design plan, large glass door openings “allow the garden view to become an ever-changing exhibit for the museum,” she said. The outdoor area balances low-maintenance plantings with open areas designed for seating, museum functions, and the permanent outdoor sculpture collection. Seating areas for viewing sculptures are surrounded by plant material that blends into the landscape. The art museum has integrated these plans into its current capital fundraising plan.

Modeling Sustainability

Today’s museums often feel the need to establish and model sustainability bona fides through audience-pleasing features and practices. Institutions that would like to entertain a deeper level of landscape enhancement, communicate green values and build a useful public programming platform can find ready help. For example, the Sustainable Sites Initiative (SITES), a collaboration of the American Society of Landscape Architects, the United States Botanic Garden and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, has created voluntary national guidelines and performance standards for sustainable landscapes that serve a broad environmental conservation agenda. SITES provides a set of tools to guide land managers in the five critical areas of hydrology, soils, vegetation, materials, and human health and well-being so that resulting landscapes are more sustainable.

The Louisiana Children’s Museum in New Orleans is in the midst of a capital campaign to relocate its facilities to a new 12-acre site that will embrace SITES principles. The Early Learning Village will include a nature center, edible gardens, multipurpose outdoor spaces and “discovery walks” intended to teach visitors about land and water ecosystems. “When we heard of the SITES program, we embraced it as a way to teach environmental education to young children and their families who will be visiting the campus,” said museum CEO Julia Bland in an e-mail message. “Their stewardship practices will be critical for our state’s long-term environmental health.”

Engineering Green into the Future of Any Museum

What about museums that have no land frontage, are located on the fifth floor, or have no apparent ability to offer the comfort and stimulus of plants to their visitors? With the emergence of increasingly sophisticated and eye popping vertical wall technology, the only limit to green in landless venues is the cost of going up, or sometimes carving out corners in patios or generously lit indoor spaces.

While the American museum scene has some celebrated examples of roof gardens such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden, European and Asian museums show particularly strong energy and a spirit of experimentation in nontraditional plantscapes.

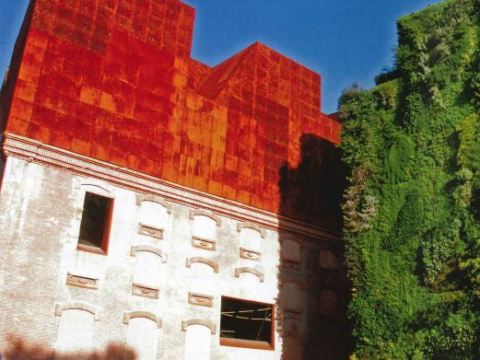

The National Museum of Scotland’s roof offers a bog garden and vista of Edinburgh. The Ghibli Museum Roof Terrace in Mitaka, Japan, is unabashedly delightful in its use of terracing and flamboyant plant forms. And the CaixaForum Museum in Madrid sports one of French designer Patrick Blanc’s camera-loving vertical gardens; an elaborate tapestry of vines, perennials and shrubs, all densely packed into planting pockets at a 180-degree angle from the viewer’s perspective on an adjacent wall. The sheer number of vertical garden images posted online attests to the power of these up-ended landscapes to attract and captivate.

James Corner Field Operations, the design firm that created New York City’s Highline (a one-mile-long elevated park built along a former train line) is redesigning Chicago’s Navy Pier public spaces on the shores of Lake Michigan. Corner’s vision integrates amusement rides, shops, and restaurants with cultural institutions including a children’s museum and Shakespeare theater. “Part of our job has been to try and better relate interior uses and programs with exterior, and to significantly upgrade the exterior environment- the ‘pierscape,'” said Corner. “At Navy Pier, there is sufficient structure to be able to incorporate plants, including some large trees, and given the social agenda, plants are highly desirable.”

Many believe that there is an instinctive connection between human beings and other living systems; a hypothesis called biophilia. The Economics of Biophilia, a 2012 report published by environmental consulting firm Terrapin Bright Green Progressive, amasses a wide variety of contemporary studies supporting its claim that biophilic design optimizes productivity, healing time, learning functions, attention span, positive feeling, readiness to spend and community cohesion. Proponents would argue that plants and landscapes make people feel happier, more relaxed, more receptive to a museum’s core message and more inclined to come back. The power of green not only invites in new and different audiences but can equilibrate and enhance our human function. Progressive museums that closely monitor cultural trends would be wise to consider plants in their future plans.

Patsy Benveniste is vice president of education and community programs, Chicago Botanic Garden, and serves on the board of the American Public Gardens Association.

Sharon Lee is co·author of Public Garden Management, the first textbook to examine the operations and management of a public garden, and the former deputy director of the American Public Gardens Association.

Donald A. Rakow is the Elizabeth Newman Wilds Director of Cornell Plantations, serves as associate professor in the Cornell Department of Horticulture and director of the Cornell Graduate Program in Public Garden Leadership, Ithaca, NY, and is co-author of Public Garden Management.

Comments