This article originally appeared in the May/June 2013 edition of the Museum magazine.

An adult diaper, a pill box, a plain spiral notebook, a yellow sponge, a mess of bank documents, a photo album, a broom. Each of these items rests in a specially constructed vitrine at the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum in Chicago, thoughtfully arranged by a group of preparators and curators, propped up on stands, secured with museum wax. These everyday, seemingly disposable objects have been given the full museum treatment in a historic house museum, and are the focal point of a new exhibit that makes visible the invisible labor that has been done in the home for centuries, and makes crucial connections across history within a space that itself speaks to the matter at hand domestic work.

“Unfinished Business: 21st Century Home Economics” is an exhibition that transformed a historic house museum into a vibrant space of inquiry about a pressing contemporary issue, while simultaneously maintaining a commitment to transformation of the visitor, the community, the nature of an exhibition and institutional structures. This exhibition challenged our most basic conceptions about museum practices, including those around curatorial authority, how to write an effective object label and what makes for a relevant, resonant artifact. It also expanded the horizon of our imaginations and aspirations for the potential impact of an exhibition on social change.

Our museum preserves the history of Jane Addams-America’s first woman to win the Nobel Peace prize and the founder of the Settlement House movement. At the turn of the 20th century, middle-class settlement workers like Addams moved into working-class neighborhoods and grappled with the modern, industrialized city alongside their neighbors. Settlement Houses made social change through cultural programming, policy reform and direct service.

At the Hull-House Museum, we have taken up the mantra, “Never again will a single story be told as though it’s the only one,” a quotation from art critic and writer John Berger that infuses much of the work we do. Not only do we explore the life of Jane Addams, but we tell the stories of the many reformers, immigrants and neighbors who lived, worked and played at the Hull-House.

Yet, despite our commitment to include many diverse voices in the museum, it was many years before our staff turned its attention to an obvious question that speaks to the nature of domestic life and led us to undertake an exciting partnership with community groups around the city: Who did the domestic work at the Hull-House Settlement?

As a historic house, we had read and watched as our colleagues at places like Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia, and Chicago’s Driehaus Museum had integrated the slaves and servants who once labored in those old houses into the museum experience-struggling to find the appropriate way to acknowledge those lives that had gone largely undocumented and been made invisible by history.

Hull-House is a very different site than these other historic houses. The settlement thrived as a utopian experiment in

democracy- a place that strived for equality and participation for all who lived, worked and played there. It was both a domestic space and a space of social change. Because of this, the staff had long believed that these issues did not confront us as museum practitioners in the same way as other historic mansions.

As we researched the nature of domestic labor at Hull-House, we discovered that when pioneer settlement workers Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr opened the doors of the Hull-House settlement, they did so with the help of Mary Keyser, a housekeeper and crucial contributor to Hull-House Settlement. Until her death, Keyser ran the household and shouldered the work of domestic life so that other residents could do a wide range of work that made Hull-House a crucial space for democracy. Keyser also actively participated in helping to organize other domestic workers as the head of the Labor Bureau for Women, working as both a domestic servant and social reformer. She made crucial connections in the neighborhood surrounding Hull-House and brought her knowledge of the needs and lives of the immigrant neighbors into the settlement house project. She was so beloved by the community that upon her death, her obituary ran in several newspapers and hundreds of people attended her funeral.

Keyser’s story is one example of how the work that takes place in domestic space has been undervalued as labor and largely forgotten in conventional historical narratives. Domestic labor activists and feminist theorists like Silvia Federicci and Selma James have long talked about domestic labor as invisible labor-work that is often not even considered to be work because it is typically performed for low or no pay, done mostly by women and people of color, and located in the home. Our museum had neglected to acknowledge the contributions of Keyser and the other servants who helped maintain Hull-House, and thus, we were participating in this pattern. After we discovered Keyser’s fascinating story, we created an ambitious exhibition that would not only acknowledge her work but investigate invisible labor and domestic work both in the time of the Hull-House Settlement and in our contemporary moment.

The result was “Unfinished Business: 21st Century Home Economics,” an exhibit that explores the work of the pioneering first generation of Progressive Home Economists and investigates contemporary models of social justice in domestic space through community partnerships with artists, scholars, and activists. In this exhibit, we make crucial connections across history and bring the artifacts and stories of living domestic workers into a historic space, asserting that while much progress has been made on the issues that Jane Addams and other reformers worked on during the Progressive Era, there is still significant “unfinished business.”

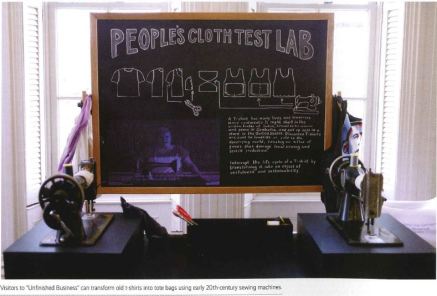

This is an unusual tack for an historic site. We gave over an entire room in our small historic house to explore the contemporary issues raised by the early Home Economics movement and made direct connections between the Progressive Era and today. Visitors are not meant to merely gaze upon old-fashioned sewing machines and imagine the labor of 19th-century garment workers. Instead, they are asked to sit down and use these sewing machines to transform an old t-shirt into a tote bag as they contemplate their role as consumers in society. We not only present Keyser’s story and display an iron she might have used, we also display the artifacts of contemporary domestic workers who, like Keyser, are both taking care of domestic spaces and fighting for fair working conditions for all domestic workers.

Despite the efforts of early 20th-century reformers and domestic workers to advocate for fair working conditions, domestic workers were left out of key labor legislation throughout the past century, and now face some of the most difficult working conditions of any group of workers in the United States. In most states, including Illinois, domestic workers are not guaranteed a minimum wage, have no paid time off or benefits, and face difficult working conditions that include risk of injury, little sleep, and isolation from family and community. Most domestic workers are women, immigrants and people of color, and take care of those things we say we value most as a society-children, parents, elders, neighbors and homes.

In Chicago, a growing coalition of labor unions, individual workers, scholars, and activists has recently .formed to push for new legislation advocating for domestic workers’ rights in Illinois. In the early stages of the exhibition process, we turned to the Chicago Coalition for Household Workers to understand domestic work in Chicago and make connections in the community. What we discovered was a rich and fruitful partnership with a group of dynamic, thoughtful women from around the world who saw cultural work as a key part of their mission as community organizers.

In our first meeting, we put forward the possibility of community curation, a methodology that the Hull-House Museum has used in several exhibitions, based on models presented in texts like Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World, a collection of case studies and conversations that provides a jumping-off point for community engagement. Although there are always surprises in any collaborative relationship, what we discovered through the community curatorial process with the Chicago Coalition of Household Workers was an exciting new kind of collaboration- one that blended the missions of two very different organizations and allowed the museum to become a partner in social change by creating avenues for empathy, education, and cultural activism.

One difficulty that can come from community curation is a false sense of reciprocity. As a museum, we gain much from including the voices and artifacts of under-represented communities in our space. It is often less clear what they gain from the experience. The process can feel like the re-inscription of a colonialist project of plundering artifacts from a community group so that the museum can display them safely within the sanitized gallery space. The staff of the Hull-House Museum attempted to disrupt this dynamic in two key ways, aided by the feedback and ideas of the collaborators.

First, we went into the partnership with the domestic workers with the intention of situating the domestic worker rights’ movement in a long historical narrative, bridging and blending contemporary and historical activism. By doing this, we would make connections across time and demonstrate to visitors and community collaborators alike the historical roots of the problems we face, and the innovative solutions that have been presented in the past. In this way, we hoped to arouse the radical imagination of our partners and visitors, reminding all involved, including our own staff, that there are many innovative solutions yet to be tried. This historical perspective was something that we could offer as a site rooted in labor and women’s history, and one that we hoped would facilitate reciprocity with the coalition.

As we sat with the domestic workers at our first meeting and pitched them the idea behind the exhibit, the story of Keyser surprised and excited them. Although they, of course, knew the history of the troubling labor legislation that had caused the conditions they now faced, they had not yet connected to historic domestic workers who also struggled for better working conditions. Many of the workers connected personally with Keyser-herself a worker and organizer-and they were excited that the exhibit they would curate would be made in conjunction with changes to our permanent exhibit that would include Keyser’s artifacts and story for the first time. Myrla Baldonado, one of the primary organizers with Chicago Coalition of Household Workers, and a Filipina immigrant and longtime domestic worker, connected so completely with the story of Keyser that she dressed up as her for Halloween. She often commented on how much Keyser’s commitment to changing the plight of domestic workers in the 1800s felt very familiar to her and the work she is doing today.

Second, we maintained a constant dialogue with the domestic workers about what they were hoping to get out of the curatorial and exhibition process and blended the mission of the museum with that of the coalition to create a synthesized vision for the exhibition. The coalition hoped the exhibition would do the difficult work of transforming the public understanding of domestic work: highlighting the labor struggle while demonstrating the dignity and love inherent in the work itself. Because we were working with a community group with very clear and concrete goals-passing legislation, changing the attitudes that people have about domestic work-we were able to create a mutually beneficial relationship in which both groups could work towards each others’ goals as well as their own.

Today the exhibition serves as a teaching tool for the coalition, where they can bring domestic workers, reporters and those curious about their cause to understand it through artifacts and story, and within the context of a broader historic narrative. They also take our history into the world, talking about the history of social reform and the power of exhibition practices at protests and organizing events. Collectively, we blurred the lines of curator, museum professional, and community member, rather than merely bridging our differences.

In choosing how to display the artifacts and words provided by our collaborators, we took seriously the “museum effect” described by art historian and critic Svetlana Alpers in her essay, “The Museum as a Way of Seeing.” We knew that by bringing the artifacts of domestic work into the museum, we were asking that they be taken seriously as objects of history and art, and we wanted to push the visitor to examine her own ideas of what deserves to be placed within the venerable walls of a museum. And so we took a blue adult diaper and placed it in an expensive vitrine.

The artifacts donated by the domestic workers are visually arresting. A visitor is confronted not just by any vernacular object, but by a used pill box and foreclosure documentsitems that ask a visitor to empathize with some of life’s harshest realities. This empathetic response was one of the key goals of the exhibition. The workers wanted visitors to understand the many facets involved with care work: It is physically taxing and underpaid, but it is also an act of love. It was for this reason that Baldonado brought forward a scrapbook titled “Sally, the best babysitter on earth,” full of photographs of her friend and fellow caregiver, Sally Richmond, with the family she cared for.

Although the artifacts themselves are powerful as representations of work and care, the labels that accompany them are perhaps more visceral and notable. The labels were written during a workshop conducted by a facilitator from Young Chicago Authors, a creative writing and youth spoken-word organization that cultivates new creative voices in Chicago. In this workshop, domestic workers wrote funny, heartfelt, poetic pieces that serve as labels for their artifacts. In many ways, these labels disrupt the usual conventions of label writing- they are long, meandering and written almost as prose-poems- and yet they are perhaps the most effective labels in our museum. Nearly every member of our staff who read the labels, including the designer who laid them out and the preparator who mounted them on mat-board, was moved to tears by the specificity and intensity of the stories and the broader realities they spoke to.

This label, written by domestic worker Lisa Thomas, identifies a yellow sponge:

I wake up at 5:30, I leave home at 6:00 take that long ride-Lake Snore and Belmont. I get to work. Sutter’s sons let me in the apartment, and when I walk in the door Sutter says “Lisa is that you? I was so worried you would not come. I’m ready to eat.” These were her first words every day. She weighed 450 pounds. Her arms were as big as a 250 pound woman. Her stomach was so big that it took me and her three sons to lift it. We put pillows under the arm. Pillows under the stomach. Rolled sheets between the legs to make it easier to wash I would use a large sponge. I would use a hospital bucket to put water in to wash her hair. First it took about an hour to wash her hair. Her hair was long and grey and it could touch her feet. The pillows underneath her arms because they were so big one person could not lift them as I began to wash her with the sponge she would tell me, “the not water feels so good.” After the arms we washed her stomach. We bad three pillows under her stomach. I washed it in sections. She would thank me the whole time. It took two hours to bathe her and then change the sheets. We bad to pull her over to one side of the bed. Me and two brothers lifting and pulling her back. I go around and tuck the sheet up under her as far as I can. Then we do the same thing to this other side after I cover her with a sheet because she doesn’t nave anything big enough to wear. After I fix her breakfast. She gets 4 waffles, 6 eggs, and 7 sausages. After breakfast I clean the bedroom, the bathroom, the dining room, the kitchen. At this point, I nave already been there two hours over my time. While I’m cleaning she moans. She is still hungry. She cries for more food. The doctors nave her on a strict diet. Before I leave I would give her two not dogs.

For the museum, this exhibit has been an incredible success. Even after it had only been open for a month, we already had visitors connecting deeply to the history and seeing themselves within it. A group of au pairs visited the museum and wrote afterward to describe how the exhibit influenced them, saying it “helps people to change a little bit the way they look at the world, you know? At least, it changed my way to look at everything.” They went on to ask for resources on both how to create a museum and how they might obtain better working conditions themselves.

The power of “Unfinished Business: 21st Century Home Economics” lies in both process and form. Through an innovative collaboration process, the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum and the Chicago Coalition of Household Workers created an exhibit that blended the needs of both organizations. What emerged was a space that not only interrogates the past but the present, not only promotes education but encourages activism, not only asks its visitors to contemplate but encourages them to empathize, not only provides a space for the artifacts of the domestic workers but gives voice to their labor and their lives. By honestly interrogating the history of our site, and making crucial connections to the present, we were able to make our site not only a space that raised questions about the past, but a space of contemporary social change.

Heather Radke is exhibition coordinator, Jane Addams Hull-House Museum, Chicago.

Comments