A reporter recently asked me to name the biggest barrier standing in the way of museums adapting to the forces shaping the future. My reply was “ourselves—the funding and organizational structures that tether us to outdated models and failed strategies.” However unsuccessful these models are, sometimes the barrier that keeps us from discarding outdated ways of operating is simply too high to scale. Hence my pleasure in sharing the story of the Oakland Museum of California—a story that illustrates how massive disruption can be turned into an opportunity for reinvention and growth. OCMA Director and CEO Lori Fogarty has spoken eloquently about this transformation at conferences—in today’s guest post, she shares a brief version of the ongoing saga.

Elizabeth cited our recent reorganization at the Oakland Museum of California in her July 11 post about the need for museums to let go of assumptions in order to meet the real needs of their communities – up to and including the assumption of traditional organizational structures and authority. There has been a good deal of interest in our experiment here in organizational change, so I thought I’d elaborate on this tale of how disruption and potential upheaval resulted in new possibilities and ways of working for OMCA.

As a brief background, OMCA had been a department of the City of Oakland since its founding in 1969. Funded entirely by the City for its first few years, public support had declined significantly over the decades, and as a result, a private non-profit entity, the OMCA Foundation, was founded in the early 1990s to provide fundraising assistance for exhibitions and programs. By 2010, the balance had tilted so that City funding represented 45% of our budget, and support through the Foundation totaled 55%. The City funding – which was declining more precipitously with the recession and Oakland’s financial crisis – was almost entirely directed to facility operations and maintenance and, most significantly, to salaries and benefits for the 45% of our staff who were City employees. Even at a time when were in the midst of a major capital project and institutional resurgence, we were facing the potential of severe employee lay-offs due to City reductions.

Instead of viewing this prospect as inevitable, we pursued complex negotiations to restructure our relationship with the City, resulting in the City turning overall operations to the OMCA Foundation while retaining ownership of the facilities and collections and continuing to provide substantial – though reduced – annual funding. What that meant in reality for our staff was that the City would lay-off all employees at the Museum — myself included — and the Foundation would then make the determination whether or not to re-hire. And, by contract with the City’s unions, we were required to give six months notification of the impending lay-offs.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleWhile the prospect of this kind of enormous change could have been morale-busting for employees, we decided to seize this opportunity to truly reinvent the structure of the Museum. When OMCA was founded in the 1960s, it came together as three smaller museums of California art, history, and natural science, and we still operated in many ways as three museums, bifurcated even further between City and Foundation staff. With the City transfer, we could put this legacy aside and invent the Museum we wanted for the future – an institution that would put the visitor and community participation at the very core of our organization.

As the City and Foundation Board leadership negotiated the intricate agreements that would enable the transfer, I worked with museum organizational consultant, Gail Anderson, and the staff of the Museum to envision what a structure for a 21stcentury museum might look like. With as much transparency and communication as was feasible during the highly sensitive and political process with the City, we formed working groups of staff charged with considering how we might improve processes and systems, redefine roles, and create a collaborative, cross-functional structure in support of our mission and vision for the future.

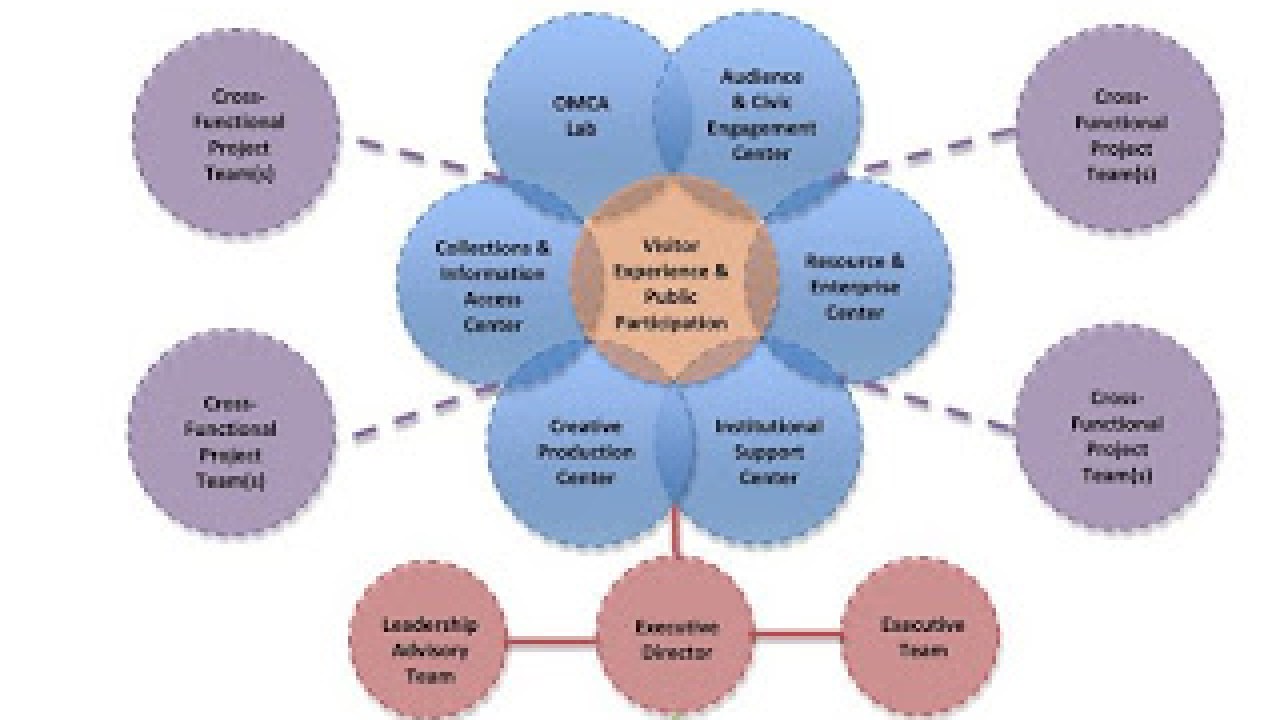

The result of this process was a structure that is reflected in an org chart that is affectionately known internally as “the flower.” The structure incorporates six cross-functional, cross-disciplinary “centers,” all focused on an outstanding visitor experience and participatory community engagement. These six centers are: the OMCA Lab; the Audience & Civic Engagement Center; the Creative Production Center; the Collections & Information Access Center; the Resource & Enterprise Center; and the Institutional Support Center.

As part of the process, we re-wrote every job description. Every staff person whose job underwent extensive change—whether former City employee or current Foundation employee—was required to interview for a position, which meant conducting 90 interviews in a six-week period. With a very small number of exceptions, we were able to retain everyone who applied to the new organization and, at the same time, attract great new talent and cultivate new leadership. As disruptive as this process was – and, of course, the day-to-day work of the Museum continued unabated during the months of this transition – the restructuring enabled a fundamental and profound cultural shift and new ways of working throughout the institution.

So, how are we doing now two years into our organizational transformation? When we embarked on this journey, I felt we were in a boat at sea, tossing around in turbulent waters, without a compass or life preservers. I can now say with confidence that we’ve landed, pitched our tent on the shore, and our new “flower” structure and culture is taking root.

Comments