I’ve blogged about my brief experience with Google Glass at the Tech@LEAD conference. Turns out @nealstimler loaned that same pair of specs to Nik Honeysett, head of administration at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Today Nik shares his musings on the implications of this new technology, prompted by his ‘test drive.”

It really is getting ridiculous. We’ve barely figured out iPads, we still regard browsing our museum websites from a desktop as our primary use case and now Google Glass is staring us down. Yes, I have purloined said shiny gadget (thanks @nealstimler). It’s been a while since total strangers have stopped me in the street (or galleries in this case), questioned me about what I’m wearing, and asked if they can try it on. It used to happen a lot, but that’s a different post. With my “recovering technologist” hat on, I’ll say that Glass has that intoxicating feel of new technology that’s going to be a big deal, still a little clunky, but significant. It smells disruptive.

However, the impending arrival of Glass begs the question, how do we keep up with technologies that will significantly disrupt how we deliver content to our audiences? And the disruption isn’t about something new or different, it’s about an addition, an added complexity. Just because Glass is arriving, doesn’t mean tablets are leaving. James Gleick, author of The Information (ISBN-10: 1400096235) said it far more elegantly:

“Hardly any information technology goes obsolete, each one throws its predecessors into relief”

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleIt appears we’re on a three year cycle, iPhone (2007), iPad (2010) and now with Glass we’re already on to a totally different mode for delivery, really different. Responsive design gets us out of the hole for simultaneously delivering content to desktop, tablet and phone, but responsive design will not help us deliver to Glass.

In three years, we’re going from the convenience of a light-weight, hi-res, touchscreen computer with the natural gesture of pinch and zoom, to something we wear instead of carry, command by voice and even wink at to control. We’re competing for the attention of our audiences, and nothing gets closer to our audience or more personal than Glass’ “screen”. The only reason Google is inventing the driverless car is so that we can wear Glass while driving. You think I’m joking? Google’s revenue model is about eyes on ads, ads don’t get closer to your eyes than with Glass, and there’s no greater captive audience than a driver in a car.

So as I learn to interact with Glass, and apply a fake American accent to increase the success rate of my voice commands, it’s brought into focus (enough with the puns already) what’s required of us as museums. The organisational simplicity of data and information that Glass requires informs a strategy to survive and scale up in the face of rapidly changing delivery technologies: Ignore the technology and focus on the trend. I’ll invoke Occam’s razor:

A scientific and philosophic rule that entities should not be multiplied unnecessarily … the simplest of competing theories be preferred to the more complex … explanations of unknown phenomena be sought first in terms of known quantities.

(“Occam’s Razor.” Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster)

The strategy is simple enough: in the same way that a sound financial strategy says, “look after the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves”, we need an information strategy that provides for the simplest delivery, because the complex delivery technologies can take care of themselves. It will also let others, who do a far better job of presentation and who are far better equipped to deal with the sustainability issues, worry about the delivery. Rather than packaging our information, using our own resources to wrap it up into neat self-contained bundles, we need to become service-oriented, we need to get into the resource creation business where we provide the data and others provide the presentation. I’ll use two examples from my own institution, the Getty’s Open Content Program and our recent partnership with Khan Academy.

The focus of the Open Content Program is to make all public domain artworks in the Getty’s collections free to use, modify, and publish for any purpose and at high resolution. While we will continue to provide access by wrapping up our collection images in a convenient self-contained, collections-online subsite, so can anyone else. We created the resources, but we’re letting others do stuff with them, and we’ll be releasing more images over time (currently we’re at 10,000). Fortunately we have a Digital Asset Management system that allows us to manage and deploy these resources. But it is not just about images, our plans are to add data to the Program as well.

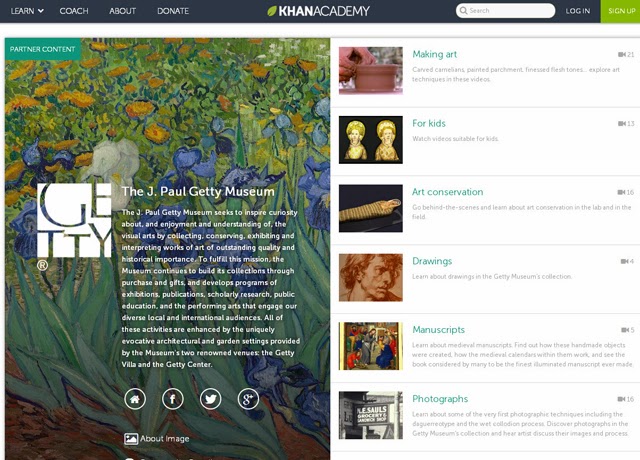

Our partnership with Khan Academy is where this concept of resource creation really takes off and demonstrates the power of this approach. Our first step with KA is to simply provide access to the video resources we have generated. In much the same way that we create playlists on our YouTube channel, KA has created similar playlists on their platform, but with this partnership we’ve doubled the return on our investment in terms of access—KA has 10 million unique users per month.Our partnership with KA will evolve to create and add more content around these resources, but we can use and deploy these resources anywhere.

The concept is not new. Creating Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to provide access to our collection information and images is exactly the same concept, we just need to extend it from collections information to education, conservation, research, and so on, creating discrete resources, efficiently managed, deployable and accessible that allow anyone to aggregate, mix, re-mix, extend. Anyone in your museum got the time to add Glassware development to their developer’s burgeoning list of skills and then manage a project to deliver a Glass app? Probably not. Anyone got the time to reformat that descriptive or interpretive copy and add it to Wikipedia? Most likely.

Google Glass is clearly a new technology, but the trend is information delivery. In another three years’ time I could be posting about Google Implant—just another extension of the same trend. If I have done a good job of organizing and setting free my data and resources for Glass, my only worry will be about the surgeon’s blade.

We are in the thick of rebuilding our online collections and creating an open api to our collections. Out of the blue I get a request from a Board member to figure out a way to charge for access to the collections. (I thought that fire was put out years ago. I know all the arguments for and against, and am not looking for those here.) So, I am asking this group, has anybody done any serious research into fee for access to online collections? Anybody trying to do it? Any success or failure stories?

Thanks for your question. John. I put this out on the @futureofmuseums twitter feed–let's see if anyone responds