This Monday’s 15 minute musing.

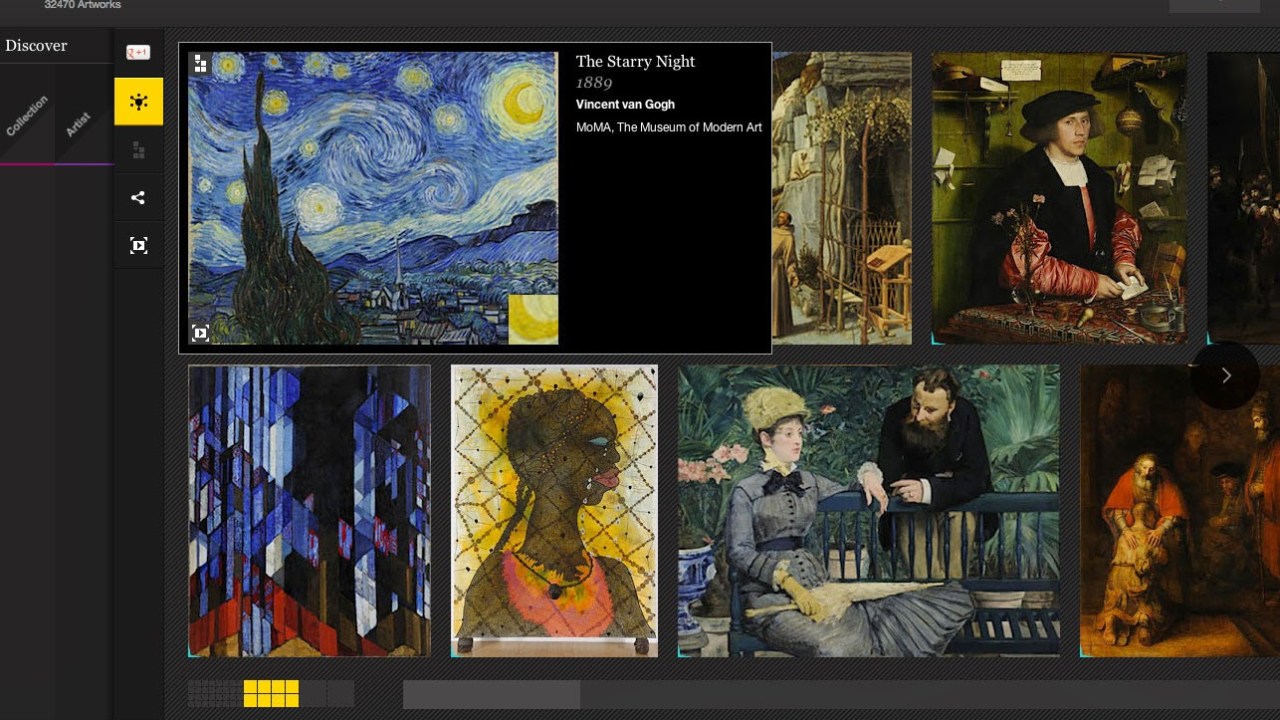

Last week Amit Sood, director of the Google Cultural Institute, announcedthat 15 new museums were launching exhibits on the Google Art Project. That project is gaining serious momentum—the article reports that the Cultural Institute hosts:

Last week Amit Sood, director of the Google Cultural Institute, announcedthat 15 new museums were launching exhibits on the Google Art Project. That project is gaining serious momentum—the article reports that the Cultural Institute hosts:

- 500 partners from over 60 countries

- 6.2 million objects and artifacts

- 19 million unique visitors from June 2013 to June 2014

- 200 million page views in just one year

Sood has evidently picked up on a nervous vibe in the museum field about the effect of free access to high quality digital art from around the globe, because he goes out of his way to make the case that virtual visits are good for museums. After the Hamburg’s Archaeological Museum posted its collection online on the Google Art Project, they received over 80,000 views in the first seven weeks, he notes, quoting the Hamburg collections manager as saying “ “We believe these virtual visits will be followed by many real visits. Sood also emphasizes the potential for digital artifacts to supplement physical exhibits, mentioning that a digital copy of Wheatfield with Crows was “one of the most popular attractions” in a Van Gogh exhibit staged at the Musee d’Orsay. (Which would weird me out more if I hadn’t already read about the all-digital Van Gogh: The Ultimate Collectionexhibit in Amsterdam—home of the Van Gogh Museum—that was such a hit. No, I take it back. That still weirds me out.)

“Open access,” concludes Sood, “means a larger audience and more recognition for artists, their artwork and museums.”

I agree, though mostly based on faith, not proof. We are only beginning to untangle the relationship between how we engage with virtual and physical objects. That’s why I was heartened to come across this article inthe Yale Daily News. Researchers at the Yale School of Management set out to explore why we value an original piece of artwork more than an exact duplicate. (Or, as Susie Wilkening has asked, why can historical objects have cooties?) The results of the YSM study suggest the value we place on original art is due to “magical contagion”—the fact that people feel objects embody the essence of their creator in some way, that “A piece of the person is literally rubbed off on the object.”

The next question I hope researchers tackle is—do people value a high res digital reproduction of a fake Van Gogh less than a high res digital reproduction of an authentic painting? And does thinking about that make your head hurt?

|

| Image from PC World |

I think about the same questions whenever people suggest I include ebooks in my little outdoor reading rooms. Don't forget the performative nature of looking at/reading real things, vs. something on a screen, and the importance of context. When we look at a painting on a wall in a museum, or open a book, we know in the back of our minds that people can see what we are doing, and that gets some positive reinforcement signals firing in our brains. (Or something like that -scientists back me up?) I can see this happening at the Uni. It's in public, and people perform. Where's the performance when looking at art on a screen?

"That generally means people who are more affluent, and people who can rely on support from their families. That often means women. It often means people from families with a tradition of academia, families that value the trade-off of salary for scholarship."

You had me until this portion where you offer no data at all to back up your claim of who constitutes those who can afford to pay the price of entry.

I find in my anecdotal experience that it is not academic families that pay the way but more crudely wealth that draws the line. It does not restrict gender, or level of scholarship in the field. Simply put if you are wealthy you are in. After all these same individuals are then expected to interact with more wealthy people in various ways to secure donations. There is a glass ceiling in museums but it isn't about pay it is about the ability to not need a job. Hard work and intelligence need not be perquisites.

This is a disturbing trend across disciplines. The decide between those born into money and those who are not is becoming wider.

It is a grotesque manipulation of what was once a means of education for those without a degree in the field, or persons changing the direction of their employment. It was never meant to be mined for free labor and a mechanism for keeping out the educated working classes.

Hi Mom. I think perhaps you meant to leave this comment on the Blog post for October 28, on unpaid internships?

Thank you for challenging me to support that statement, which I labored to condense, for this post.

I can document that 80% of the graduate students of museum studies programs are female. http://acumen.lib.ua.edu/content/u0015/0000001/0000906/u0015_0000001_0000906.pdf

Regarding why this is so–I too have to fall back on anecdotal experience, and personal conversations. When I travel around the country to speak, I make a point of sitting down with local museum studies students whenever possible. One of the things I ask them, if they feel comfortable answering, is whether they have taken on educational debt to earn the MS degree, and how they can afford that financial burden. Often they tell me they are able to do so because of support from their husband, or their parents. (I'm not sure where the 20% of MS students who are men are hiding, but there are rarely more than one or two, if any, in the groups I meet with. None of this small set have volunteered they are being supported by their wives.) In terms of "academic families that value the trade-off of salary for scholarship" I admit I am on shakier ground. For that proposition, I lean on speculation from long and recurring discussions with friends about the challenges of diversifying the nonprofit workforce. Some people propose that it is simply a matter of pay–if you come from a socioeconomically challenged family (which often covaries with racial minority status, in the US). this proposition goes, you are likely to want to make significant money with your education. But I hear others say this is a condescending attitude–that people who are the first in their families to go to college are just as likely to value mission-driven, poorly paid work. Why don't more people with this economic/demographic background go into museums, then? I'm intrigued by the line of argument, advanced by some of my conversants, that the barrier is cultura/social–i.e, not the money per se by but a broader set of family pressures about appropriate/desirable careers. This aligns with my experience, as I have many friends working in museums who don't come from wealthy families, but many of them come from families that do value education and scholarship.

So no, I can't prove that assertion. And I'd love to see more hard data that helps unpick the reasons people do, or don't, decide to make the economic sacrifice that working in a museum often entails.