This article originally appeared in the January/February 2015 edition of the Museum magazine.

Of necessity, museums that document the nation’s civil rights struggle must also confront the litany of moral wrongs committed against African Americans—particularly as we observe the 50th anniversary of the civil rights movement

and the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.

This commemoration has been underway for some time and in many different ways. A 2008 Association of African American Museums survey of 159 U.S. institutions actively curating some aspect of black history revealed a range from the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum in Chicago to the W.C. Handy Home and Museum in Florence, Alabama, honoring the famed blues artist. The association analysis notes that while some African American cultural organizations opened their doors in the 19th century, the most rapid period of growth started in 1980, particularly in the South, commensurate with increasing black economic and political influence.

Whether the anniversary timing is deliberate or coincidental, new museums with a mission to spotlight civil rights or black culture and history are either opening their doors or rapidly taking shape on the drawing board.

This road of sacrifice and protest will take you from the nation’s capital to largely Southern landmarks of shame and hard-fought redemption.

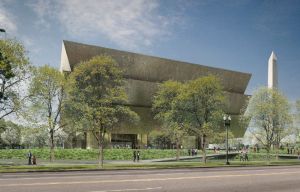

“Understanding the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act really is not just a teachable moment about the civil right movement but [having] Americans remember how they’ve expanded their liberty based on the actions of a small group of people,” says Lonnie Bunch, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, currently under construction in Washington, DC.

Like any museum, one devoted to civil rights builds your knowledge and alters your perceptions in new and unexpected ways. What sets these institutions apart is that they showcase not only artifacts and a particular time or place, but ideas and aspirations. It’s not just what’s within the museum’s four walls but what that content has to say about the world outside.

Civil rights museums hope to educate without preaching, inspire without pandering and, while rethinking the evils of the past, avoid casting a pall on the future. They transform artifacts like the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, into a sober reminder that as recently as 1960, many African Americans were unable to enjoy a cup of coffee in the immediate company of whites. Known as the “Greensboro Four,” a group of young black men insisting on their right to be served at the segregated counter became a highly publicized and powerful symbol of resistance. Their gesture of defiance grew into a massive national protest by some 70,000 people who peacefully targeted segregation in churches, libraries, beaches and swimming pools. On Tuesday, July 26, 1960, the Greensboro lunch counter was finally desegregated—and now resides at Greensboro’s International Civil Rights Center and Museum.

During the Freedom Summer of 1964, activists seized a pivotal moment to protest racism. Later that year, millions of Americans celebrated the passage of the Civil Rights Act that outlawed discrimination based on race.

For many, remnants of that turbulent time exist only as black-and-white TV news clips. Living memories fade, and many architects of that era have disappeared along with them. But their blueprints of reform remain. Neither those times nor their import will ever be forgotten if the ambitious efforts of civil rights museums in the South and elsewhere succeed.

In many ways, the evolution of civil rights museums mirrors the American experience, sometimes for better but often for worse. A logical starting place is Washington, DC, with the construction of the long-delayed Smithsonian museum focusing on the black experience. The $500 million structure is scheduled to open on the National Mall in 2016, after 100 turbulent years in the making. “This is a story that’s bigger than the civil rights movement,” says Bunch. The struggle to build the museum is “now seen as one of America’s most successful moments when it comes to change and transformation,” he says.

The effort dates back to 1915, when a “Committee of Colored Citizens” proposed a monument for “Colored Soldiers and Sailors who fought in the Wars of Our Country.” In the intervening century, the plan was stymied by competing priorities and legislative setbacks. Recommendations by black and white leaders to build the structure met with mixed and sometimes outrageous results.

In 1923, the U.S. Senate “authorized the construction of a monument to the ‘Faithful Colored Mammies of the South,’ inspiring protests and rebukes from African Americans all over the country,” according to a 2002 museum planning commission report detailing the frustrations that thwarted the museum’s construction. The report also notes that in 1929, President Calvin Coolidge authorized a commission to build a structure “as a tribute to the Negro’s contribution to the achievements of America.” That commission was ultimately abolished in 1934 during the Roosevelt administration and stripped of financial resources. (Congress still found enough money in the depths of the Great Depression to build the Jefferson memorial; FDR personally laid the cornerstone in 1939.)

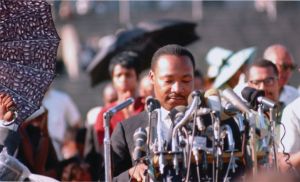

Interest in the museum resurged after the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. But the turning point came in 1989 when the Smithsonian “began to shift from outright opposition or indifference to the project to out-and-out support,” the 2002 report explains. With Rep. John Lewis (D-GA) as its longtime congressional champion, a bipartisan bill to establish the museum finally passed in 2003, but the groundbreaking didn’t take place until 2012. It was a bittersweet occasion. “The problems we face today as a nation make it plain that there is still a great deal of pain that needs to be healed. The stories told in this building can speak the truth that has the power to set an entire nation free,” Lewis said in prepared remarks that day.

Now 74, Lewis spearheaded black history documentation efforts that parallel his searing years at the forefront of the civil rights movement. An organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, Lewis later endured a brutal beating at the hands of the Alabama State Police during a protest march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. The Smithsonian’s Bunch describes Lewis as “a true American hero” and an inspiration. “Part of the strength of America has been that there are people who have risked all,” says Bunch.

After the struggle and sacrifice that created this museum, Bunch says he’s humbled by the opportunity to open its doors. “America’s this amazing place that is only made better when people push, prod, demand that America live

up to its ideals, and we hope we stimulate that commitment,” he says.

Museums are generally built around an existing collection. In this case, Bunch and his colleagues had to start from scratch. For two years, he picked the minds of focus groups to get their sense of African American history and culture. The eclectic results range from Louis Armstrong’s trumpet to Robert Gwathmey’s 1945 portrait of racial injustice and disenfranchisement, Poll Tax Country—an angular depiction of an archetypical Southern politician perorating from a bandstand, surrounded by pillars of the community. Lurking behind, a hooded Klansman peers ominously at the proceedings. Below are African Americans laboring in the fields.

Bunch says the museum will be divided into thirds: One part will illustrate the sweep of black history from its African American origins to the 21st century. Another floor will be devoted to cultural achievements including music, film and the fine arts. Completing the immersion, exhibits will take an in-depth look at the development of African American communities in places like Charleston, South Carolina, and the Bronx that nurtured tradition and history while encouraging innovation and technology. “My goal was to create a museum that gave the public not just what it wanted but what it needed,” says Bunch.

While the nation’s capital seems a culturally and politically appropriate place to build a museum around the African American experience, the decision to locate a new Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta might seem less obvious to some. Visitors to Atlanta flock to well-known destinations like the Coca-Cola museum (“The World of Coke”) and the CNN Center, where visitors can pretend to be news anchors reciting copy in front of a TV camera. But a million visitors also come each year to The King Center, a landmark destination dedicated to the famous civil rights

leader’s legacy. Established in 1968, the National Park Service complex includes King’s birthplace and tomb, as well as the Ebenezer Baptist Church where he preached his philosophy of nonviolent protest.

Backers of the new center, such as former Atlanta Mayor and United Nations Ambassador Andrew Young, saw the need for an institution that would approach the Atlanta-based launch of the civil rights crusade from yet another perspective. Doug Shipman, the center’s chief executive officer, says his institution has a unique and powerful pull. “We really took a storytelling approach for those who did not live through the movement,” he says. “We’re not artifacts driven.”

Since the $80 million, 43,000-square-foot facility opened last June, Shipman says, the exhibits have drawn the strongest reaction from Millennials who may be experiencing the emotions of the civil rights era for the first time. Among the most compelling displays, he says, is a reproduction of a lunch counter like the one in Greensboro. This one recreates the sit-ins of the early ’60s. It isn’t a passive visitor experience. When you sit down at the counter, you are subjected to recorded racist taunts and threats (e.g., “I’m going to stab you in the neck with a fork”). Eerily, the chairs jolt as if you’re being kicked. “People are constantly walking out in tears. It’s something you could never forget … the incredible sacrifices the demonstrators made,” says Shipman.

There are three main galleries: One displays a collection on loan from Morehouse College of King’s papers, letters,

notes and sermons. Called “Voice to the Voiceless,” the exhibit spotlights King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech on a black granite wall in 25 different languages. It is intended as an evocative call to action worldwide. A second gallery moves the conversation to human rights, complete with portraits of heroes and villains (e.g., Martin Luther King

and Gandhi contrasted with Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin). You can follow your moral compass to a series of large rectangular light boxes, where composite characters describe their humanity from different perspectives: What does it mean to be gay, an ethnic minority, a victim of human trafficking? The effect and intent is that of a two-way mirror: we’re confronted with depredations of human rights and asked to look at our own attitudes and feelings. A map shows human rights discrimination hotspots in the world today. Foreign visitors sometimes experience a shock of recognition when they see what’s happening in their own countries, says Shipman.

The third (and perhaps most novel) gallery transports the visitor back to the civil rights era. Vintage TVs stacked at odd angles broadcast segregationist rants, such as “Negroes never had a better friend than the white man who turned him from a savage to a respectable person.” Another exhibit lets visitors stroll down Atlanta’s historic Auburn Avenue, once dubbed the “richest Negro street in the world.” The avenue became the city’s center of black economic and cultural life in the early part of the 20th century before spiraling into decline and then finally claiming national landmark status in 1976.

While some have complained that the Atlanta museum is overreaching by combining the topics of civil rights and human rights in the same venue, Shipman sees a logical connection. He believes that civil rights leaders are using the successes of the movement as a template to advance human rights for many different causes. Shipman sees a thread from Gandhi to King to Mandela. The human rights theme “strengthens the civil rights narrative,” he says.

Given the museum’s powerful content and its reasonable admission price of $15, Shipman believes his institution is competitive with Atlanta’s other blue ribbon attractions.

Meanwhile in Memphis, the shrine-like National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel unveiled a new look at

the past with a $27.5 million renovation completed last April. The structure is built on the site of King’s April 4, 1968 assassination. Tied to the 50th anniversary of the civil rights movement and the anniversary of King’s death, the reopening played to a “packed house,” says museum President Beverly Robertson. Some 200,000 visitors come

each year to the Memphis museum, and Robertson says admissions have spiked since the renovation.

The enhanced 52,000-square-foot structure has many new offerings, including a real bus that recalls the boycott tactics that began in the ’50s in Montgomery, Alabama. Visitors can sit next to a life-sized statue of Rosa Parks—famed for her refusal to move to the back of a city bus—and hear a recorded speech by King supporting efforts to end segregation.

What was it like to come to America on a slave ship? Another exhibit shows sculptures of Africans shackled below deck, while a mural of the dock above reveals the full cruelty of the slave trade. Robertson notes that there were 12.5 million slaves transported to America before the practice ended in the early 19th century.

Similar to the Atlanta museum, the renovated Memphis institution uses updated scholarship techniques to actively involve visitors. “We want people to have an emotional experience and to leave understanding some things they didn’t have a clue about,” says Robertson. “Hopefully, you’ll be inspired to do something that will make a difference.”

Even though Robertson has worked at the museum for 17 years, she always feels the spirit of what she calls this “sacred space.” Room 306, where King spent his last night, is the museum’s physical and spiritual core. Its completely

ordinary appearance makes what happened there so extraordinary. There are coffee cups on the dresser, one bed is partially made and a dial telephone sits on the nightstand. It’s just as it was before the moment when King stepped out onto the balcony and into history.

This is a contemporary Calvary for arguably the movement’s greatest martyr, but Robertson says her museum also honors the sacrifices made by countless others for the cause. “We’re talking about people who were prepared to die for a commitment,” she says. “By connecting the past with the present, we want to remind people that unless we pay attention, we can make the same mistakes again.”

The past and the present are very much alive in Mississippi, where plans to build the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum are well underway. The institution will take on the challenge of candidly explaining the state’s history of racial violence and intolerance. “The concept is we’re going to tell the truth, and we’re not going to sugarcoat it,” says Jacqueline Dace, project manager of the museum that’s scheduled to open in December 2017.

Dace’s goal is to highlight dark events like the 1963 assassination of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers by the Ku Klux Klan. She’s shed tears with Evers’s widow, Myrlie Evers-Williams, and empathizes with many others who are still recovering from devastating experiences they endured in the civil rights era. “They deserve to have this story told, not just for the living but for those who died,” she says.

Mississippi’s racist past notwithstanding, the effort is being supported with state tax money. After years of debate, former Governor Haley Barbour (R) pushed a bill through the state legislature in 2011 authorizing the construction of a state history museum and a civil rights museum on the same site, with a combined $100 million price tag. No other state government has made that kind of commitment.

Some say Barbour was politically motivated to bolster black support in an unsuccessful bid for the White House. Whatever the reason, Dace is looking at the positive. She does not believe that juxtaposing a Mississippi history museum with a civil rights museum was intended to enhance the reputation of the former and diminish the importance of the latter. “The civil rights story is so synonymous with Mississippi, and it’s so large, it needs its own museum,” she says.

A big part of that story is the mutual work of blacks and whites to advance human rights, Dace says. Included are not just the generals who came to Mississippi but foot soldiers under the banners of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). “It has to be inspirational, and by telling the story it will be inspirational,” says Dace.

The 18,000-square-foot display space will focus on the period from 1945 to 1976. There will be eight galleries surrounding a 40-foot-tall sculpture called This Little Light of Mine, whose arms will extend throughout the museum and illuminate as visitors travel throughout the other exhibits, ultimately bathing them in light. The symbolism is an artistic reminder that each individual effort, no matter how small, together made a profound contribution to the civil rights struggle.

Three galleries will feature multimedia presentations detailing hate crimes among the most notorious in the struggle for civil rights: the brutal murder of 14-year old Emmett Till in 1955, Evers’s assassination and the killing of three civil rights workers who were registering black voters in 1964. Historical records show that 581 people were lynched in Mississippi between 1882 and 1968, the highest number of any state. Quoting longtime activist Bob Moses, Dace says, “When you’re in Mississippi, the rest of the world doesn’t seem real, and when you’re in the rest of the world, Mississippi doesn’t seem real.”

Demonstrating the reality of the American slave trade is one ambitious goal of the International African American Museum planned to open in 2017 in Charleston, South Carolina. Mayor of the city for nearly four decades, Joseph Riley has taken on the project as a personal mission. “It’s going to happen, and it’s going to be wonderful,” he says. “It’s an African American history museum, not a civil rights museum.”

The aim is to tell the story of slavery starting in Africa and how so many victims wound up in Charleston’s Gadsden’s Wharf as a point of entry. According to the museum’s website, around 100,000 West Africans landed there between 1783 and 1808. The museum is planned for that actual spot and will chronicle African American history from the days of slavery up to and including the civil rights era.

So far, Riley and museum supporters have raised about $30 million of the projected $75 million needed to build the 43,000-square-foot structure, even though some in the community believe the funds should be allocated to other local priorities. While Riley may have quieted the skeptics in Charleston, he still has to convince the state legislature to come up with $25 million in funding—a task he had hoped to avoid. Still, he remains optimistic. “I found great interest in it, and lots of support,” he says.

Riley hopes construction will begin in 2016. Exhibit plans do not include lots of artifacts. “The artifact really is the city. You walk through the city and see the buildings that were constructed by Africans and their descendants,” says Riley.

He believes that a museum retelling Charleston’s history through an African American prism will increase civic pride, with a commensurate boost to tourism supporting the local economy. “We see it as being very inspirational, and certainly honoring those who came through difficulties and persevered,” says Riley.

Like the civil rights movement, museums about the struggle have different views, approaches and messages. They are tunes played by different instruments. Yet Lonnie Bunch hears a collective symphony of freedom. “No good historian would say that he or she is doing the only defining story,” he says. “What we realize is that people will come to the Smithsonian who won’t go to museums in their local community. What we want to do is recognize the work of those local museums and push people back.”

The focus on civil rights just 50 years after the movement’s apex acknowledges the importance of the cause. But struggles don’t end on a date certain. Each museum in its own way tells a story of justice denied, rights won and the battles that lie ahead. Fifty years mark an end and a beginning. Civil rights museums have opened the doors of understanding to a period that challenged and changed America. It is up to those who were there to explain what happened to those who came after. It is in the end not just about race, or even civil rights. It is about who we are and what we will become.

Jeff Levine is a freelance writer living in Rockville, Maryland. He was one of CNN’s founding correspondents in 1980. During his nearly 20-year career with the network, he reported from a number of U.S. cities, including Atlanta, and also served as CNN’s Israel bureau chief.