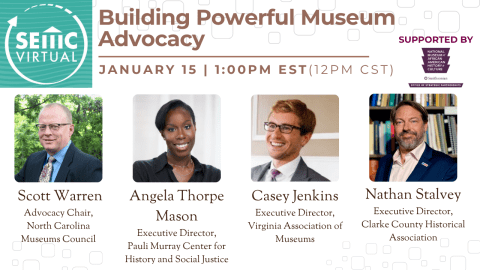

I was delighted to hear this story over the weekend on NPR, on how the Pacific Science Center opens early, one Saturday each month, to provide an environment tailored to the needs of visitors with autism. For this time, they turn down the lights, tone down the noise and reduce the crowds, resulting in a quiet, calm experience that better suits the needs of children and young adults on the autism disorder spectrum.

|

| From NPR story on the Pacific Science Center’sdedicated hours for families with ASD photo credit: Jennifer Wing, KPLU |

Many of the trends I write about push museums in opposing directions: the rise of hand-held, internet connected devices opens the door to a proliferation of digital content; fatigue with digital overload results in visitors who just want to disconnect. Some visitors thrive on putting themselves into the museum picture (literally), while others are driven nuts by the antics of people taking cell-phone pics (with or without a selfie stick). Some people want a boisterous, gamified, participatory experience, many just want quiet (and if possible, solitary) contemplation.

What’s a museum to do?

Some, faced with these conflicting forces, will go all-in with one strategy or another: saturate the museum with opportunities for digital engagement, or go relentlessly offline (perhaps going so far as emulating the small but growing number of cafes that turn off the WiFi). But most museums are going to have to accommodate visitors with divergent needs and preferences through either spatial or temporal partitioning. Want to encourage parents to bring their babies to the museum? You could create “baby zones” throughout the museum, or you could set aside hours specifically for moms and dads to bring their babies to the museum, and not have to feel self-conscious about drool, poop, crying and other normal aspects of the whole baby experience.

In this case, PacSci (among other museums with similar programs) chose temporal partitioning as a way to tailor the museum experience to the needs of people with autism. Other museums are staying open late, sometimes all night, to attract new audiences. As Nina Simon has discussed, later hours can make the museum accessible to working people, create symbiotic experiences with other night-life events, and buffer the public from school tours.

The other dimension a museum can play with is space—either chunking out different parts of the museum building for different kinds of experiences (like the aforementioned baby zones), or co-opting other space. That’s what the Walker Art Center did when they started Open Field—dedicating the sloping lawn outside the museum to summer activities that embody the “creative spirit of our community.” (And birthing the awesome Internet Cat Video Festival.) That’s what the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh did with the Charm Bracelet Project, partnering with other local museums and community organizations to revitalize underutilized city spaces like the New Hazlett Theater and Buhl Community Park. The Detroit Institute of Arts has gone even farther afield, infiltrating communities up to 30 miles away with their Inside/Out installations.

|

| Infant and Toddler Playspace at the Children’s Museum of the Low Country |

Both these strategies—temporal and spatial partitioning—are very much in the spirit of the sharing economy, which is based on milking value from underused resources. Looking outside the normal boundaries of a museum’s habits of operating inside its own walls, between 10-5 Tuesday through Sunday, can create the space and time to create tailored experiences for different user groups.

There are potential downsides—staying open later may cut down on the museum’s revenue from evening rentals (as well as increasing operating costs). People who encounter “distributed” events and installations may not connect them with the museum. But overall, erasing the traditional boundaries around time and space is relatively affordable way of creating a bigger pool of resources, so different groups can have experiences personalized to their needs.

And remember–if there’s an unmet demand, , outside your open hours, for the kind of experience your museum provides; or if people want a kind of experience inside your museum that you aren’t providing, some other business may well step in to fill that need and snatch that potential market out from under you. You might decide to pass on these opportunities (maybe they lie to far outside your mission. Maybe you’d rather partner with these entrepreneurs than compete), but it should be a conscious, considered choice. Don’t miss the chance to make your museum accessible to people when they need you, how they need you, just because it takes you outside your cultural comfort zone.

And remember–if there’s an unmet demand, , outside your open hours, for the kind of experience your museum provides; or if people want a kind of experience inside your museum that you aren’t providing, some other business may well step in to fill that need and snatch that potential market out from under you. You might decide to pass on these opportunities (maybe they lie to far outside your mission. Maybe you’d rather partner with these entrepreneurs than compete), but it should be a conscious, considered choice. Don’t miss the chance to make your museum accessible to people when they need you, how they need you, just because it takes you outside your cultural comfort zone.

(DIA–Inside/Out)