Back in 2001 AAM sponsored a survey which showed that 87% of respondents viewed museums as “one of the most trustworthy sources of objective information.” We cited that figure a lot in the following decade. commissioned by the Institute for Museum and Library Services also showed that museum visitors overall rated museums very highly on trustworthiness–4.62 on a scale of 1-5.)

But Jim Gardner has an uncomfortable take on that data. (Jim is in charge of the presidential libraries and museum services at the National Archives, and before that was director of curatorial affairs at the National Museum of American History). Jim suspects people trust museums because they think we present unmediated facts, in the form of our collections. They don’t realize museums even do“interpretation,” selecting and arranging objects that support a particular argument or point of view, shaping the visitor experience through how the exhibit is designed, how the label text is written. That’s a pretty depressing thought.

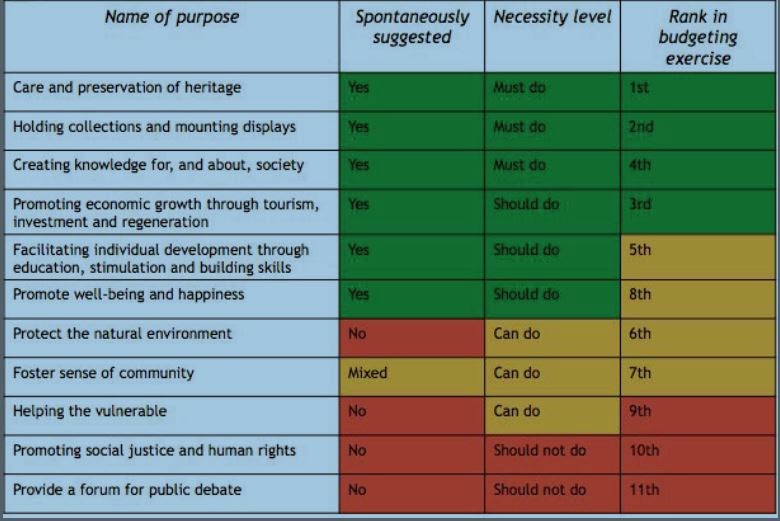

I remembered Jim’s skepticism when I recently revisited some 2013 research from the (U.K.) Museums Association on public perceptions of—and attitudes to—the purposes of museums in society. The Museums Association conducted focus group studies to inform their Museums 2020 initiative, which is designed to build public and government support (and funding) for the sector. To this end, they convened focus groups to answer the question “what do citizens consider to be the most important purposes and roles against which public funding for museums should deliver?” The study addressed this in a number of creative ways, including giving participants a “budget” to spend on various museum functions, and asking them to envision what might lead to the demise of museums in the future.

In line with the AAM and IMLS research, the Museums Association research found that museums hold a unique position of trust, especially in contrast to the media and government. Why? Because museums are seen as “guardians of factual information” that “present all sides of the story.” <

When invited to weigh in on what does not fit in the essential purposes of museums, the UK participants listed promoting justice and human rights, and providing a forum for debate. These activities were cited as “undermin[ing] the essential values of trust and integrity that people cherish with regards to museums.”

Untangling some of the nuances of that feedback, the report notes that the panelists felt museums:

Can address controversial subjects, but should address all sides of the issue while remaining neutral, rather than taking a stand; can appropriately have a “moral standpoint” but not a political standpoint—museums are expected to give “unbiased and non-politically driven information,”

That’s particularly sobering in a time when, at least here in the US, science is becoming widely politicized. Media, similarly pressured to provide “balanced” coverage ends up presenting opposing views as if they have equal credibility.. most notably “balancing” scientists documenting climate change with the rare scientist who is a climate change denier. How would this translate to expectations of museum coverage of an issue? Does presenting scientific consensus on the projected consequences of climate change constitute taking a political stand? Currently even the issue of vaccination is becoming politicized, with the current Republican presidential candidates taking stands on parental choice.

Here are a couple of particularly sobering quotes from the Museums Association study:

“Adopting a subjective and opinionated stance, or seeking to influence visitors’ opinions, is strongly opposed and would be seen as infringing the museum’s trusted objectivity.” Said one participant “if I want someone telling me what to think, I’ll pick up a newspaper or turn on the telly. That’s not what museums are there for.”

I find this particularly sobering as we approach the Alliance’s annual meeting in Atlanta, with its theme of “The Social Value of Museums: Inspiring Change.” I’ve pointed out before that museums may have to choose one of two roles: facilitator or advocate, between being a trusted place for dialog and taking a stand on an issue. If a museum advocates action on climate change or human rights, or simply maintains the scientific reality of evolution, it may close the door to engaging with people who disagree with these positions, and end up preaching to the converted.

What I hadn’t considered is that the public might reject both those roles, as indeed the participants in the U.K study did. “The idea that a museum would go out of its way to incorporate controversial or divisive topics was seen as puzzling and [was] branded a ‘must not’ purpose. Furthermore, debates and controversy were seen as possibly undermining one of the core museum purposes, namely to provide a family-friendly, enjoyable and entertaining day out.”

From: Public Perceptions of–and attitudes to–the

From: Public Perceptions of–and attitudes to–the

purposes of museums in society. Britain Thinks for

Museums Association, March 2013.

Edelman’s 2015 global Trust Barometer research shows Americans overall trust the public nonprofit sector more than their British counterparts do, but doesn’t give any indication that the behavior that earnsthat trust (for government, companies, or NGOs) is any different in the U.S. than across the pond. Do we have any reason to believe the U.S. is fundamentally different than the U.K. when it comes to public trust and museums? American museums overall receive very little government support compared to their U.K. counterparts. Perhaps the source of museums’ funding may influence public opinion about museums’ public responsibilities. I suspect not, however, if only because I think most people are pretty fuzzy on where U.S. museums get their money to begin with.

Mostly what I want you to take away from this mishmash of information, these hints and indicators, is the realization that museums can’t take trust for granted. If the public trusts American museums more than the government, or business, or the media, we can’t assume it’s because they trust our expertise, or our opinions. (Another sobering nugget in the Edelman report: when it comes to content creation, people trust their friends and families as much as they trust academic experts.) And if we want the public’s trust, that might mean having to stick to “just the facts.” Even if we think the “facts” (as embodied in our collections) don’t speak for themselves.

Wow – this is a fascinating study. On the one hand, it reinforces the idea that people may have antiquated ideas about what museums are for or ought to be for (I can imagine a similar report about libraries emphasizing the necessity of books everywhere). On the other hand, especially in England, these are the voters who largely fund museums. I'm very curious if people who do not engage much with museums responded, and if so, what they seek.

Makes me think both about how we can be responsive to people's interests/needs/perceptions AND move to where we see the needs and opportunities shifting in our communities. Tough work.

Thanks so much for sharing this. I found your comments, and the report itself, very stimulating. One thing jumped out at me: your comment, from Jim Gardner, that “people trust museums because they think we present unmediated facts, in the form of our collections” resonated with something that Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett said way back in 1991: “true to what I would call the fetish-of-the-true-cross approach – objects, those material fragments that we can carry away, are accorded a higher quotient of realness” which she attributed to “the legacy of Renaissance antiquarians” (Objects of Ethnography. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display: 394). So, are we obligated to forever replicate this legacy, or is it not time to re-position that so-called trust?

Let’s also tease apart the report a bit. I went through it–admittedly pretty quickly–but it really struck me that at every opportunity the report writers took the most conservative and cautious tack. For instance, in comments on “public debate,” the authors acknowledge that the word “debate” was problematic and prompted negative reactions from respondents. For that reason, the topic tumbled to the bottom of the list. But looking at the comments, it seems clear that respondents were not uncomfortable with presentations that had a position, or that took a side. So, while I find this report useful and interesting, I think it leaves lots of room for “debate.”

Peter Welsh

My mind went to the very same place (re: Barbara K-G's essay). This report seems to suggest (also) that people may well be cognizant of the museum aura affect and fear that making it too transparent will entail work (vs. entertainment) or complete collapse. Interesting findings.

Thank you for building on the conversation Nina, Peter and Museum Anthropologist. I agree that the report is very conservative and cautious: I believe because it is explicitly building a case for public funding. Which brings us (as usual, in my mind) to the question of museums' business model. The people who pay for a service ought to be able to control what they get from it. If you are edgy and take risks…and people end up loving it, good for you! The Apple stockholders were probably on edge every time Steve Jobs got up there on stage to announce the next great thing people didn't (yet) know they wanted. But Jobs was a genius, and usually nailed it. If a museum wants to take on largely unpopular positions, or roles, they need to find a cadre of people willing to support that work as donors or members. But since museums collectively are supported by the American taxpayers (via our nonprofit status), the overall perception of museums has to be that we play a useful (preferably vital) role in society. That may mean either being more conservative than some may prefer, or cutting loose from public funding and enjoying the freedom that comes from an income stream derived from people who approve of how you are operating.

If I may comment from a UK perspective, I feel that the Britain Thinks research should be treated with caution.

Some of the methodologies used – such as asking members of the public to allocate notional spend against possible different purposes of museums – were interesting and challenging. However, the research has been criticised in the UK for the inept ways in which these methodologies have been applied – for example, in using misleading descriptors and asking leading questions, to a degree that some of its conclusions – at least in my view – should be almost entirely discounted.

The Museums Association (MA) itself has made it clear that this research was just one contribution among many to a wider discussion on the role of museums. The MA did not endorse its conclusions, which in some cases significantly conflicted with other research on public perceptions of museums in the UK. For the MA's position, based on a wide-ranging consultation, please see instead the MA's policy document, Museums Change Lives, published in 2013.

Several of us from the MA will present a session at the AAM conference in Atlanta this year on the role of museums in society, and will look forward to debating these issues further there!

David Anderson,

President, UK Museums Association

Since Beth quotes me in the blog, I think I should provide the context for my comments. Some years ago, I wrote about the challenges history museums faced, with specific concern about the findings of the Rosenzweig and Thelen study (1998) of history making in the US. Rosenzweig and Thelen found that the public trusts museums “as much as they did their grandmothers” (p. 195). The public, according to that study, believe that museums stand for authenticity and accuracy in a way that professors, teachers, and books do not. AA number of my colleagues saw that as a good thing, but I did not–Rosenzweig and Thelen explained that the public feel they can go to museums and interpret artifacts as they want, unmediated, without concern that ideas are being interposed between them and the objects. In other words, the public really don’t get what museums do, that we too have perspectives, make choices, present arguments, just like colleagues elsewhere. The difference is that the objects we exhibit and the institutional contexts in which we work confer authority and validity on our work, an authority and validity that I’m uncomfortable claiming. SO I argued for opening up the process, sharing what we do and why, not just the end products of our work. While I was focusing on the original US study, it has since been replicated in Canada, Australia, and perhaps other national contexts–with similar findings.

Jim Gardner, National Archives

Thank you for weighing in, David and Jim. Readers–David's session with his colleagues from the Museums Association is titled "Agents of Change or More of the Same," and it will take place on Sunday, April 26 from 2-3:15 pm. I'll also include it in my 2015 "Guide to the Future at the Annual Meeting" which will come out on the Blog a few weeks before the meeting.

Jim–thank you for letting me riff on your observation, and for writing in to provide context for the original comment.

Thanks, Beth, for initiating this stimulating and important discussion. Several comments proposed that a kind of outmoded view of museums as guardians of the true story of a nation’s history and culture persists and seems to be reflected in the studies mentioned. It isn’t clear whether people who don’t ordinarily go to museums were included in these studies, but it seems to me that there are people in both our countries who are aware that the stories they see in museums ARE interpreted and filtered, and for that reason these people stay away. The mainstream filters and interpretations do not contain, or misrepresent, their stories. Despite many improvements in this area, I still hear this anecdotally in particular from African American and Native American friends and colleagues. This was a topic of discussion recently in Carol Bossert’s interview with Porchia Moore on the satellite radio program Museum Life (see the podcast for January 30, 2015). See also an interesting study by Emily Dawson, “Not Designed for Us: How Science Museums…Exclude Low Income, Minority Groups” http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sce.21133/abstract

Despite efforts at diversifying our stories and interpretations, I believe that most museums continue with the same general narratives, pleasing those who already come and missing out on opportunities to engage with the people who stay away. If museums are to be and be seen to be “vital” to their communities (writ large, not just the usual white, middle class, well educated audiences) then they do need to begin addressing issues that are of concern to wider communities. Sometimes simply having an open forum, with expert speakers, on a controversial issue can be seen by some as “taking sides.” But I think that museums need to educate their publics that the concept of “museum as forum” is a legitimate and long held one in the field.

I also don’t see this issue in the either/or perspective that you suggest: “That may mean either being more conservative than some may prefer, or cutting loose from public funding and enjoying the freedom that comes from an income stream derived from people who approve of how you are operating.” It seems to me there is a value in museums individually as well as collectively through AAM and other professional organizations in

1) Educating politicians and both private and public funders on the contributions museums can make as safe and appropriate places for reflection and discussion of difficult topics. W

2) Providing support, not necessarily financial but philosophical and moral support for museums that wish to address difficult issues – science museums on climate change, history museums on legacy of race, etc. Fellow museums and/or museum associations could provide education, webinars, perhaps even some kind of recognition for museums that work or wish to work effectively in these areas.

In other words changing the public’s perception of the role of museums is mostly up to us in the field. I think we can work more actively and intentionally on this than we have in the past. AAM’s upcoming conference in April is a great opportunity think about how to do this.

Thanks, Beth, for initiating this stimulating and important discussion. Several comments proposed that a kind of outmoded view of museums as guardians of the true story of a nation’s history and culture persists and seems to be reflected in the studies mentioned. It isn’t clear whether people who don’t ordinarily go to museums were included in these studies, but it seems to me that there are people in both our countries who are aware that the stories they see in museums ARE interpreted and filtered, and for that reason these people stay away. The mainstream filters and interpretations do not contain, or misrepresent, their stories. Despite many improvements in this area, I still hear this anecdotally in particular from African American and Native American friends and colleagues. This was a topic of discussion recently in Carol Bossert’s interview with Porchia Moore on the satellite radio program Museum Life (see the podcast for January 30, 2015). See also an interesting study by Emily Dawson, “Not Designed for Us: How Science Museums…Exclude Low Income, Minority Groups” http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sce.21133/abstract

Despite efforts at diversifying our stories and interpretations, I believe that most museums continue with the same general narratives, pleasing those who already come and missing out on opportunities to engage with the people who stay away. If museums are to be and be seen to be “vital” to their communities (writ large, not just the usual white, middle class, well educated audiences) then they do need to begin addressing issues that are of concern to wider communities. Sometimes simply having an open forum, with expert speakers, on a controversial issue can be seen by some as “taking sides.” But I think that museums need to educate their publics that the concept of “museum as forum” is a legitimate and long held one in the field.

I also don’t see this issue in the either/or perspective that you suggest: “That may mean either being more conservative than some may prefer, or cutting loose from public funding and enjoying the freedom that comes from an income stream derived from people who approve of how you are operating.” It seems to me there is a value in museums individually as well as collectively through AAM and other professional organizations in

1) Educating politicians and both private and public funders on the contributions museums can make as safe and appropriate places for reflection and discussion of difficult topics. W

2) Providing support, not necessarily financial but philosophical and moral support for museums that wish to address difficult issues – science museums on climate change, history museums on legacy of race, etc. Fellow museums and/or museum associations could provide education, webinars, perhaps even some kind of recognition for museums that work or wish to work effectively in these areas.

In other words changing the public’s perception of the role of museums is mostly up to us in the field. I think we can work more actively and intentionally on this than we have in the past. AAM’s upcoming conference in April is a great opportunity think about how to do this.

Thanks Beth for reporting on the findings of the UK survey. I have to admit I have always been somewhat uncomfortable about the notion (though sincere) as museums as agents of social change. Providing an experience is in itself an outcome that is replete with possibility: perhaps that experience did not result in taking away the content the museum set as an indicator of success of achieving it educational goal yet that visitor’s life could have been changed forever that very day. If we go back to the summer 1999 issue of Daedalus, that was entirely devoted to America’s museums, Harold Skramstad, set an agenda for the twenty-first century museum to take as its mission “nothing less than to engage actively in the design and delivery of experience…” The other overarching theme was for museums to become more outward –rather-than inward focused—by inclusively involving its community in planning processes. Over the years, museums have come up close and personal to its surrounding communities formed strong relationships and realized incredibly innovative exhibits, programs and initiatives through many rewarding collaborative partnerships. In the process, museums have turned an empathetic lens to their communities—not a bad thing, but even a good thing can be taken too far for in wanting to “help” their community by solving the problem the community identified or not, the inherent danger always there is that the effort would be seen as “overstepping.” Once the museum sets itself as the identifier and the solver of the problem—or even the helper—the danger is that it can be perceived as opportunistic (i.e. using as its target population: poor children and/or adults in x urban area for grant funding application to do xyz) for a well-intended project to improve a situation but could be misread by same target that “we are incapable (not smart enough) of solving our own problems” or “given the opportunity, would have taken a completely different approach.” As a former director of an historic house museum in an urban city racked by racial riots in 1968, I too fell into the latter category and have since shifted my thinking. In sending my community college students to museums over the past 25 years, I have learned from them that once having received the guided direction from my class lectures, to please step out of the way and allow us go on our own to the museum to make our own discoveries. Their first-person self reports let me know when I have succeeded for they reported life-changing insights from that museum experience, on occasion, simply an enjoyable one. In both cases, they write they loved the museum experience and vowed to return even when the class ended. Alfred North Whitehead saw nothing wrong with the term “leisure.” In fact, he saw it as those rare times in which people can choose to think what they want to think and how and to him, there was nothing more democratic for in doing so it often was the greatest stretch of which their minds were capable. That has been my takeaway from teaching community college students who are not privileged and who for the most part, have never been asked what they think—about anything. Yet their museum experience gives them a new-found confidence in their own cognitive abilities because their selected object piqued their curiosity so that when they self-constructed a problem for themselves and determinedly set out to solve it, they arrived at a wholly new insight—about another culture, about the world and most surprising to them, about themselves.

Terri McNichol

Developer imaginement http://renassociates.com