“How do we plan for a future in which change, and water, are the new normal?” —Urban Land Institute Boston

While politicians and pundits continue to argue about climate change, nearly everyone else—including oil companies, the insurance industry and the U.S. military—are buckling down to deal with reality. Despite Al Gore’s newfound optimism about avoiding the worst consequences of climate change, we have a lot to work out. Over a century of data helps us plot the trajectory of change (in C02 levels, temperature, sea level) and model future ecologies, but the data can only inform our choices—they don’t give us answers. Whether and how to build, whether to move or abandon homes or whole communities, crafting the best approach to weathering storms and tides—planning on this scale will determine what cities and nations look like centuries from now, even as we deal with immediate consequences. Museums, as stewards of cultural heritage, are in it for the long term. To safeguard the artistic, historic and scientific resources they hold in trust for the public, museums need to adapt to a world where change—and water—are the new normal.

In the last half of the 20th century, insurance underwriters could quantify and manage risk based on a century or more of data about floods, fire, drought, storm and other natural occurrences that humans deem disasters. Now the accelerating rate of climate change is making the old predictive models based on that data unreliable. Broad patterns are clear: sea levels are rising, and we know that large areas of coastal land will be inundated in coming centuries. Even the relatively conservative estimate by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change forecasts the global sea level could rise three feet by the end of this century. With a 10-foot rise in sea level, the U.S. would lose 28,000 square miles of land, currently home to 12.3 million people; research suggests that projection could play out in the next century. Meanwhile, nations, cities, and states are grappling with even the modest sea level rise, coupled with increased frequency of severe storms, that we are experiencing right now.

The effects of rising seas, more frequent, violent storms and flooding due to severe rain events are exacerbated by the fact that throughout history humans have settled by water, not just for practical reasons but because “blue space” has a deep positive impact on our well-being. Those patterns of settlement have been reinforced by social and economic trends that led cities, in the recent past, to reclaim abandoned industrial areas along waterfronts and uncover waterways to drive residential and retail development. These actions created short-term economic booms and helped foster high-density, resource-efficient cities, but in the long term they put more people and more real estate at risk.

Cities and states are incorporating projections of sea level rise and attendant effects into their planning—see, for example, the extensive efforts of New York City and the reports from many states including California and Maryland. The policy implications of these plans sometimes turn into political football, as when North Carolina recently shortened the time frame for its sea level projections due to an uproar from homeowners and developers about the longer-term forecasts of a 39-inch sea level rise by the end of the century (and the implications for property values). For the most part, however, policymakers, planners, designers, architects and scientists are working together to create the shape of the next century.

What This Means for Society

Cities are sinking billions of dollars into risk-proofing infrastructure (electricity, sewage, communications, public transportation) to withstand storms and flooding. But as we retrofit our cities to deal with rising tides, it’s a challenge to do so without turning cities into fortresses. And “hard” barriers like dikes, walls and floodgates are also vulnerable to catastrophic failure (as dramatized by the failure of the levees in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina). More and more often, planners are turning to “soft” barriers and resilient design that can mitigate and tolerate flooding, rather than preventing it entirely. See, for example, the mix of strategies envisioned for the “Big U” in New York City, eight miles of coastline defenses that will “blend into a newly imagined string of waterfront parks.” Even after we design workable, livable ways to mitigate risk, we face the huge challenge of altering zoning and regulation to facilitate adaptive architecture and urban design.

In addition to reshaping our built environment, we need to foster resilient local networks of emergency response to help neighborhoods recover from disaster. These networks are increasingly being woven from government, NGO and corporate partners. Several cities are launching programs that recruit sharing economy companies to help provide housing and transportation needs in event of disaster—since peer-to-peer socially networked companies like Airbnb, Lyft and Uber can respond organically and flexibly to rapidly shifting needs. Research conducted after Superstorm Sandy reinforced the literature that indicates social factors like connectedness, social cohesion, trust and community bonds contribute to the ability of communities to recover from disaster. That being so, “future proofing” cities may require investing in community institutions (including museums) that foster these social bonds.

There is only so much structural or social engineering can do to prepare for the deluge. Over the next century, we will need to decide what areas to abandon (for example, by withdrawing federal flood insurance to discourage individual homeowners from rebuilding). In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, one geologist famously suggested selling the French Quarter of New Orleans to Disney and moving the city 150 miles upstream. While that rather undiplomatic suggestion went nowhere, the Crescent City may, over time, slowly shrink away from the sustained challenges and costs of repeated storms. Other communities, less tied to a particular site by history, architecture and pride, will simply pick up and move (as did Valmeyer, Illinois, and New Pattonsburg, Missouri, after the great Mississippi floods of 1993).

What This Means for Museums

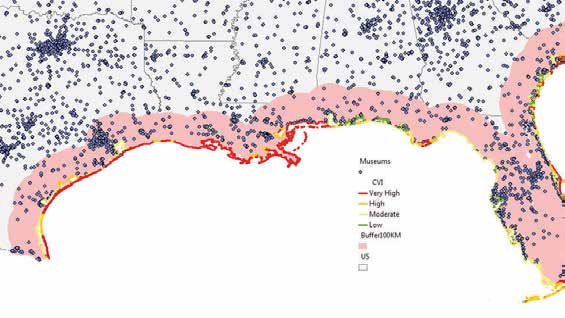

Recently, at the request of the American Alliance of Museums, IMLS used data from the Museum Universe Database File (MUDF) to identify museums and related organizations that lie within U.S. coastal areas. IMLS found that 34.6 percent (12,236 out of 35,364) of museums and related organizations are within 100 kilometers of the coast. Moreover, 25.2 percent of these organizations (8,927 out of 35,364) are within 100 kilometers of the coast identified as having a very high coastal vulnerability index (CVI). CVI provides a quantifiable measure that expresses the relative vulnerability of the coast to physical changes due to future sea level rise (Hammar-Klose and Thieler, 2001). CVI ranks coastal areas from low to very high based on the following criteria: tidal range, wave height, coastal slope, shoreline change, geomorphology and historical rate of relative sea level rise. In addition, there are over 90,000 individual historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), many of which are not represented in the IMLS dataset, that are also at risk from rising sea levels, storms, flash floods, fire and changes in the freeze/thaw cycle.

In 2009 (the most recent year for which AAM has data), the median cost of new museum construction was $1.8 million. For organizations with annual operating expenses over $4 million, that figure was $6.5 million. The top quartile of art museum construction costs over $29 million. In 2005, while the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum’s new $45 million, Frank Gehry designed campus was being built, Hurricane Katrina dumped a casino barge on the site, crushing several buildings. When a museum large or small sinks significant resources into new construction, a cold-blooded assessment of current and future risks should inform everything from choosing a building site to selecting the elements of design.

Climate change and rising sea levels affect risk and, therefore, insurance. The insurance industry is revisiting how it models risk and over what period of time. This may affect what kinds of coverage museums can get, and at what price. In addition, some museums may be sited in areas that make insurance unaffordable or unavailable in future decades. At the very least, insurance companies may have much higher expectations of what a museum must do to mitigate risk.

Risks posed by climate change also affect museum field research, not just their home base. As dramatized by Lifemapper, an online species distribution and predictive modeling tool, many organisms will need to migrate to new locations if they are to survive. This increases the value of natural history collections—which document the historical range of species—but also challenges them to create collecting research plans that will track these shifts in the world.

Museum Examples

In 2013, the Pérez Art Museum Miami opened its new $131 million building, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, right on the Miami shoreline. It boasts some of the largest hurricane resistant panes ever installed, and is listed on a “hurricane-resistant platform.” Even the hanging gardens by French botanist Patrick Blanc are billed as Category 5 hurricane resistant. (The resilience of the museum’s design is cited repeatedly in stories about the new building, no doubt because Miami is one of the top five most vulnerable cities to a landfalling hurricane, as well as being one of the U.S. cities most vulnerable to severe damage from rising sea levels.)

In 2014, the Chrysler Museum of Art completed a $24 million renovation, and nearly a half-million dollars in that budget was devoted to flood resilience. Before 1982, the inlet less than 200 feet from the museum’s front steps had never flooded for more than a hundred hours in a year. By 2009, the number of flood hours exceeded 300. The renovations also included installing floodgates on the front steps, establishing salt water-tolerant landscaping, redesigning parking and rerouting the electrical systems. Since the basement had flooded three times in the past 10 years (having been dry since the museum’s founding in 1933), they also moved the heating and air conditioning systems to the top floor. In Norfolk, Virginia, where the museum is located, tides have risen over 1-1/2 feet in the previous century, and scientists at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science projected that by the end of the 21st century, local sea levels will rise by 5-1/2 feet or more, as global sea level rises and local land sinks—which means the entire town, not just the museum, has to consider their long-term future.

In 2014, the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP) named the historic city of Annapolis one of its National Treasures. Annapolis is regularly flooded by high tides, which are expected to double in frequency by 2050. In its announcement, NTHP said, “Annapolis was selected as a National Treasure because of its irreplaceable historic and cultural significance, as well as for the steps Annapolis is taking to protect its historic structures from the threat of increased flooding and severe weather events.” The city is creating a Cultural Resource Hazard Mitigation Plan for the Annapolis Historic District to lessen the impacts of flooding and other weather-related events on the city’s historic places. Annapolis’s museums include Water Front House, Paca House & Garden, Hammond Harwood House and the Annapolis Maritime Museum.

From 2009–2010, the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in New York City hosted an architects-in-residence program to re-envision the coastlines surrounding New York Harbor, and use “soft” resilient infrastructure to mitigate the risk from sea level rise. In 2010, the Museum of Modern Art presented the resulting designs from five interdisciplinary teams in an associated exhibition, “Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront.” The proposed solutions encompassed sponge-like sidewalks, housing suspended over the water and turning the Gowanus canal into an oyster hatchery. tool, many organisms will need to migrate to new locations if they are to survive. This increases the value of natural history collections—which document the historical range of species—but also challenges them to create collecting and research plans that will track these shifts in the world.

Museums Might Want to…

- Study long-term risk projections for their current site, and make resilience a key factor driving renovations and new construction. This essay focuses on risks associated with water—flood, storm, sea level rise—but patterns of drought, fire, tornadoes and other climatic factors should be factored in as well.

- Choose sites for new construction with an eye to relevant environmental projections. For example, some museums might decide to build outside traditional cultural districts, if locations that are ideal now may soon be vulnerable and difficult or impossible to protect. Alternatively, museums may limit how much they spend on new construction, knowing those structures may be abandoned in a relatively short time frame.

- Individually or in collaboration with other museums, create offsite collections storage in areas that have lower risks, or in buildings that can be designed specifically for risk mitigation. This was considered after Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf coast in 2005, when museums in Louisiana banded together to plan for a joint inland storage facility for collections. While that plan did not come to fruition for various reasons, the idea was sound.

- Create master plans for buildings and grounds that can be adjusted every decade to adapt to changing conditions.

- Make their decisions in the context of the longterm plans of the community as a whole.

Further Reading

The Post-Sandy Initiative report, American Institute of Architects, 2013. (PDF, 44 pp.) The report summarizes recommendations for short-, medium- and long-term strategies for creating a resilient city, addressing transportation and infrastructure, housing, critical and commercial buildings, and the waterfront.

The Urban Implications of Living with Water, Urban Land Institute (ULI) Boston, 2014. (PDF, 52 pp.) This report, funded by the Kresge Foundation, arose from a conversation among over 70 experts in the fields of architecture, engineering, public policy, real estate and others. It proposes integrated solutions for future cities in an era of rising sea levels, focusing on Boston.

MitigationNation is a blog created by the National Building Museum in association with its 2014 exhibit “Designing for Disaster,” focusing on how to reduce the impact of natural disasters. The associated website includes an extensive list of “mitigation resources” organized under the headings of fire, earth(quakes), water and general (disaster preparedness).

The Future of Historic Places and Climate Change, Adam Markham. This post on the Preservation Leadership Forum Blog by the director of the Climate Impacts Initiative at the Union of Concerned Scientists addresses climate change and its impact on historic sites, structures and landscapes. http://blog.preservationleadershipforum.org

Hammar-Klose, and Thieler, E.R., 2001. Coastal Vulnerability to Sea-Level Rise: A Preliminary Database for the U.S. Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf of Mexico Coasts. U.S. Geological Survey, Digital Data Series DDS-68, 1 CD-ROM