“‘Open’ is already on track to supplant ‘participatory’ as buzzword of the year, with good reason. The proliferation of groups supporting and encouraging openness in the cultural/creative sector is impressive. Wikimedia, Creative Commons, the Open Knowledge Foundation, free software advocates, open-source software advocates: the list gets longer all the time.”—Ed Rodley

The open culture movement in all its permutations—open source, open software, open government—calls for a fundamental cultural shift from the assumption that information should be tightly controlled to the presumption that content should be made available to everybody, absent a compelling reason to keep it locked up. Open content licensing and Creative Commons copyrights encourage people to reuse, remix and redistribute material. Open source software invites programmers to mess with the underlying code. And the open data movement is racing to get information out in the world, where it can do some good. Governments are adopting open data policies and pouring money into creating open data infrastructure; companies are springing up to exploit these new resources; individuals are exploring how access to data sets empowers them as individuals, citizens and entrepreneurs. Museum data—cultural, scientific, especially operational—has traditionally been closely controlled. In a world pivoting towards open, can museums afford to be left behind?

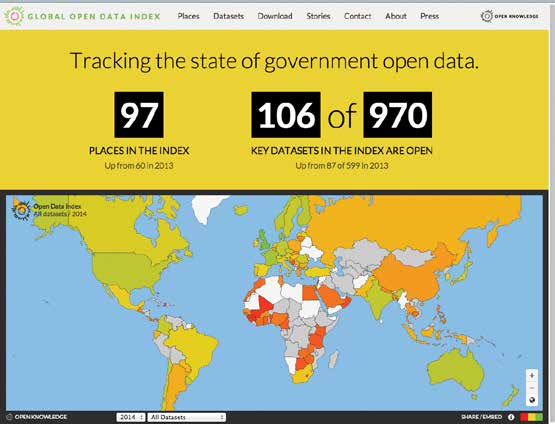

Open data is FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) on steroids. Back in the 1990s, we made a quantum leap towards openness when floppy discs supplanted poor-quality photocopies as a format for obtaining government records. Now, four years after the federal government created data.gov, that open national data repository contains more than 400,000 datasets from 175 agencies. Last fall, when Minneapolis became the 16th U.S. city to pass an open data policy, one city council member explained the

action by declaring, “It’s the people’s data, and it should be out there.”

Once data is “out there,” people find all sorts of wonderful ways to connect, analyze and mash it up to serve a variety of goals. Open data fuels civic activism and civil rights, as when the New York State Civic Engagement Table merges voting history data with data on public housing to empower community organizers. It supports scholarship and exploration, as when MapStory enables anyone to access, manipulate and annotate public domain map data to “improve our understanding of global dynamics, worldwide, over the course of history.” It transforms city planning, as when the Denver Regional Equity Atlas layers data about education, income, health and other measures of equity on plans for the new transit network.

“Open” comes at a cost, of course. Building the infrastructure to support publicly accessible databases isn’t cheap. Last year the European Union announced it was sinking the equivalent of nearly $18 million into three open data initiatives—an open data incubator, a Web data research network and an academy to train data scientists. But although the major impetus for open data is government transparency and accountability, open data systems can save money as well. City governments, for example, can use open data to monitor compliance with regulations or respond to citizen concerns in cost-efficient ways.

As the Open Knowledge Foundation points out, “Open Knowledge is what open data becomes when it is useful, useable and used.” Many barriers stand in the way of converting data to knowledge, the foremost being compatibility. Interoperability is chimerical if data sets aren’t configured to talk to each other. To this end Code for America is promulgating recommended formats to make data easier to access and use. Another thorny issue is “gray data”—data that is only half open, redacted or

partially released. With so much data backlogged, and with more being generated at an astounding rate, there is also the question of what to prioritize.

What This Means for Society

Open government data facilitates transparency, accountability and participatory democracy. But progressing from data to knowledge is not enough—we have to use knowledge wisely if it is to make the world a better place. Open data could be a force for good, as individuals and civil society organizations use public data to improve their communities, and it could be an impetus for government officials and contractors to self-censor, obfuscate or falsify information.

Open data, like digital fabrication, is a technology with the potential to catalyze economic growth, spawning jobs that replace those lost in dying industries. A growing list of private companies are building their businesses around public data, working in the realms of business data, health care, energy, education, transportation, real estate and more. The current focus of the Open Data movement is government data since we (the public) already “own” this information. Now foundations are driving openness as well—recently

The current focus of the Open Data movement is government data since we (the public) already “own” this information. Now foundations are driving openness as well—recently the Gates Foundation announced that all the research they fund must meet the standards of open access publishing, including the requirement that all the data underlying published research results be accessible and open immediately. However, many private companies (e.g., Facebook, Google) amass and monetize huge databases culled from users’ online behavior. Will we come to expect that this data (which is,in some sense, ours) be made open as well?

As we push towards “open,” society has to grapple with what data can or should remain veiled. Edward Snowden’s theft of data from the National Security Agency dramatized this issue: on one hand, the information he leaked sparked a much-needed debate on appropriate limits for covert monitoring of U.S. citizens. On the other hand, many maintain his actions seriously damaged U.S. security and strengthened world terrorism. The debate about when data should be open or closed is playing out across the country on smaller stages as well. In Honolulu, two public officials resigned because of a bill that required them to submit asset disclosures online—believing that their right to privacy trumped the public’s right to know. Recently the startup Hipcamp protested an RFP by the U.S. Forest Service for management of the Recreation.gov website, arguing that the terms of the proposal let the service provider keep too much commercially valuable data secret. When does too much openness

threaten an individual’s right to privacy, or a company’s need to protect data from competitors?

What This Means for Museums

In “The Virtues of Promiscuity,” an essay for the Code|Words project, Ed Rodley observes that a ”central part of the missions of successful museums in the present century will be, as Will Noel puts it, ‘to put the data in places where people can find it — making the data, as it were, promiscuous.’” Museums already hold their collections in trust for the public, both from an ethical and a legal perspective. Should the same principles apply to associated data? In that case, building digital infrastructure to support data sharing is as fundamental as creating exhibit galleries and collections storage facilities.

Museums traditionally regard some categories of data as secrets to be kept rather than as knowledge to be shared. For example, in natural history museums it has long been considered appropriate to redact data on collecting localities for sensitive, rare or endangered species. A recent paper in Collections Forum (see Further Reading, below) challenges this convention, arguing that all collections data should be freely accessible unless such release contravenes applicable laws or regulations; is prohibited by an agreement with the collector, donor or landowner; or is justified in restriction by “very specific circumstances” (their emphasis). What circumstances warrant exemptions to a general commitment to “open?” For museums, one important manifestation of the open culture movement is

For museums, one important manifestation of the open culture movement is open authority, which Lori Byrd Phillips has defined as “a mixing of institutional expertise with the discussions, experiences, and insights of broad audiences.” Museums are deconstructing, piece by piece, the authoritarian model that presumes control of what people see, what they learn and how they learn it. Open data vastly accelerates this trend, vaulting us into a world in which users bypass museum controls and filters and go straight to the source. That prospect can be pretty scary. Will open data deprive museums of income streams that come from mediated access? Will it mean that museum curators don’t have first crack at publishing on collections they study?

On the other hand, when museums put their data out there for users to play with, they may learn a tremendous amount about what people value about their work, and how people want to work with them.

Museum Examples

The Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt has made its entire collections database available on Github (a public database repository) using a Creative Commons “no rights reserved” license. They even wowed the Maker community by making the 3D scan data of Andrew Carnegie’s mansion (the building they inhabit) free to download, remix and reuse. Also in the spirit of “open,” the museum is giving away the “Cooper Hewitt” typeface it commissioned to mark their reopening after three years of renovation—not just the font, but the source code, so designers can mess with it. The entire digital collection of the Tate Modern is available on GitHub as well, and the museum has fostered playing with open data. In June 2014 the museum hosted “Hack

The entire digital collection of the Tate Modern is available on GitHub as well, and the museum has fostered playing with open data. In June 2014 the museum hosted “Hack the Space,” inviting participants to camp out in the museum overnight with the assignment “take any form of data and transform it into a creative digital artwork.” The winning project used a database from Chinese artist Ai Weiwei that contains the names of 5,196 children and young people who died in an earthquake in 2008. On a lighter note, a team dubbing itself the Pharmaceutically Active Crustaceans used data on how antidepressants in the human waste stream find their way into sea life, programming plush lobsters to tweet about their mood. In December 2014,

In December 2014, staff of the natural history museums of the University of Colorado- Boulder and Florida State University helped organize the CitStitch Hackathon, sponsored by iDigBio and the Zooniverse Notes from Nature Project. The hack promoted public participation in the digitization of biological collections, and was characterized as “a ground-breaking citizen-science endeavor with immediate and strong impacts in the areas of biodiversity and applied conservation.”

The Institute of Museum and Library Services’ Museum Universe Database File (MUDF) has been pulled into Github. Patrick Murray-John at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University used MUDF to create the US Museums Explorer, using a Linked Open Data connection to pull in text and photos from Wikipedia entries about museums. This application demonstrates both the power and limitations of open data: Murray-John evidently found it pretty easy to prototype the ultimate online index to browsing and searching for U.S. museums, but the results are muddied by the imperfections of the MUDF database, which is still being edited and proofed.

Museums Might Want to…

Audit their data, decide what should be made “open,” and create a timeline and budget for doing so. This audit should include an assessment of the challenges inherent in this process: What is the quality of the collections data? Are there legal restrictions on what can be released? What data should be prioritized, and why? Create policies regarding what data will be made public, and how. Consider what data, if any, will be kept confidential, and outline a rationale for those exceptions that is itself made publicly available.

Treat data as an asset to be managed, tracked and (when appropriate) monetized. Compiling data isn’t cheap, whether it is an image bank created via digital scanning or information on visitor behavior amassed from a program such as the DMA Friends. To create a balanced economy of data, museums need to invest in infrastructure and ongoing costs, and this may be supported, in part, by the sale or licensing of data, to underwrite the portion that is provided in a free and open manner.

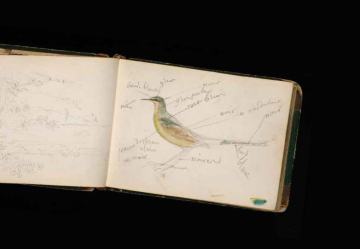

100,000 digitized images and associated metadata the

Getty Research Institute has made available via the

Digital Public Library of America. Photo: Getty Institute

850837(f.5)

Invite users to play with the museum’s data. In February 2013 the White House held its first Open Data Day Hackathon, inviting programmers and technology experts to work with White House staff to build tools using the newly released We the People API. (API stands for Application Programming Interface—a set of protocols and tools for building software applications.) Data Jams, Hackathons and Datapaloozas are becoming common, and museums can instigate their own, encouraging scientists, artists, students, technologists and the general public to mess around with the museum’s data, or play with data related to the museum’s work and share the results.

Publicize the open data available about the museum’s collections, research and operations and encourage individuals, companies and government entities to use it in their own work. This is one-way museums can contribute to civic planning, community activism, entrepreneurship and self-directed learning.

Identify what public open data could be harnessed for the museum’s own purposes—for example, city demographics, use of public and private transportation services, and school performance.

Further Reading

Ethics of Data in Civil Society, Conference Synthesis, September 2014. Lucy Bernholz and Rob Reich. (PDF, 11 pp.) Proceedings of a conference held at the Stanford University for the Ethics of Data in Civil Society Conference, September 15–16, 2014.

Beautiful Data: A Field Guide for Exploring Open Collections is a Web-based compendium of resources based on a workshop held June 16–27, 2014 at metaLAB (Harvard), supported by a grant from the Getty Foundation. The site includes a summary of the outcomes of the workshop, a prototyping game, “provocation cards” to prompt adventures in museums and case studies in the use of open data.

Policy guidelines for the development and promotion of open access, UNESCO, 2012. (PDF, 76 pp.) UNESCO’s basic text on Open Access (OA), with recommendations for formulating OA policies. Includes nonprescriptive guidelines to facilitate adoption of Open Access.

Opinion: Let Your Data Run Free? The Challenge of Data Redaction in Paleontological Collections. Christopher Norris and Susan Butts. Collection Forum 2014; 28 (1-2): 114–119. © 2014 Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections.