|

|

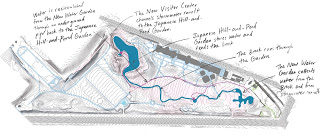

Image by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates courtesy of Brooklyn Botanic Garden

|

What if communities functioned, metaphorically, as if they were healthy wetlands? Cities and towns would respond to drought and deluge with dormancy and blooms as appropriate; they would harbor and nurture the young and vulnerable while supporting the masses; they could be beautiful, high-functioning, resilient ecosystems. They would be resilient in the face of climate change, able to absorb the shock and stresses of weather events and changing climates, and rebound in ways that strengthen and nurture the community.

Developing climate resilience is quickly becoming the work of communities and – by extension – should be the work of museums committed to their communities. Are museums, zoos, aquariums, and historical sites helping? What if they actively participated in planning and implementing community resiliency in the face of a changing climate? For museums this would be self-preservation, mission fulfillment, and demonstrating their relevance. This is what museums should do.

As thought leaders in climate and urban planning develop frameworks for community resilience, they are handing museums, zoos, gardens, and sites a stunning opportunity to contribute to their communities and build value and relevance.

Who is Doing What?

What could we be doing?

The leaders among us will be actors in community resilience. The Brooklyn Botanic Garden (BBG) is a premier example. According to the Institute of Museum and Library Services, 34.6 percent of “museums and related institutions” are within 100km of the coast, with 25.2 percent in areas of “high coastal vulnerability” (Trendswatch 2015). That includes BBG: the property’s key water feature is a manmade brook of potable water running through the property to a terminal pond. As the institution prepared to renew the feature, the leadership chose to redesign the system to recirculate the fresh water rather than release 21M gallons annually into New York Harbor. As they considered the options, Hurricane Sandy dramatically demonstrated the problem of the city’s combined sewage overflow (CSO) system.

According to BBG’s President Scot Medbury, about 200 cities nationwide have stormwater and sewage systems that merge. When wet weather events create stormwater runoff in great quantities, the merged systems overwhelm treatment plants and the overflow is released untreated to the natural waterways. BBG’s new system will use satellite information and 17 other datapoints to automatically drain a new water garden into the harbor in advance of a storm. The empty water garden can then capture and hold much of the property’s runoff without contributing to the CSO crisis. As the skies clear and waters recede, the surface stormwater can be slowly and safely released, and the system returned to design levels for circulating and filtering as appropriate.

|

|

Brooklyn Botanic Garden: Campaign for a New Century

|

- “enhances and provides protective natural and man-made assets” and

- “ensures continuity of critical services.”

Your institution does not have to engage in new construction to contribute to urban resiliency. In the “leadership and strategy” dimension museums can “empower a broad range of stakeholders” by encouraging involvement and providing information, education and access. Your site can also “promote cohesive and engaged communities” by providing safe spaces, supporting inclusivity and cultural diversity and promoting tolerance.

We know that a cohesive community responds to threats in a healthier fashion. Why not step into your community to build its resilience to whatever social, economic, and environmental stresses may come? We can and must protect more than our collections: we have a duty to protect our communities, too.

This April there is a conference in Rhode Island, Keeping History Above Water. It's a great opportunity for historic sites and landscapes to join the discussion about how to protect themselves and support their communities as sea level rises. http://www.historyabovewater.org/