TrendsWatch 2016 will go up on the web at the end of this week! And (spoiler alert) one of the topics I cover this year is the explosive rise of Augmented and Virtual Reality devices. The technology behind AR/VR is rapidly becoming more sophisticated, while costs plummet. The implications go far beyond games development: AR/VR have tremendous potential as educational tools, having been dubbed “empathy engines” for their ability to foster human connections. Museums are already exploring the potential for these technologies to enhance our practice. Today, a case in point: Peder Nelson, exhibit developer and Geoff Nunn, exhibit developer and adjunct curator for space history tell us about the Museum of Flight’s forays into the virtual realm.

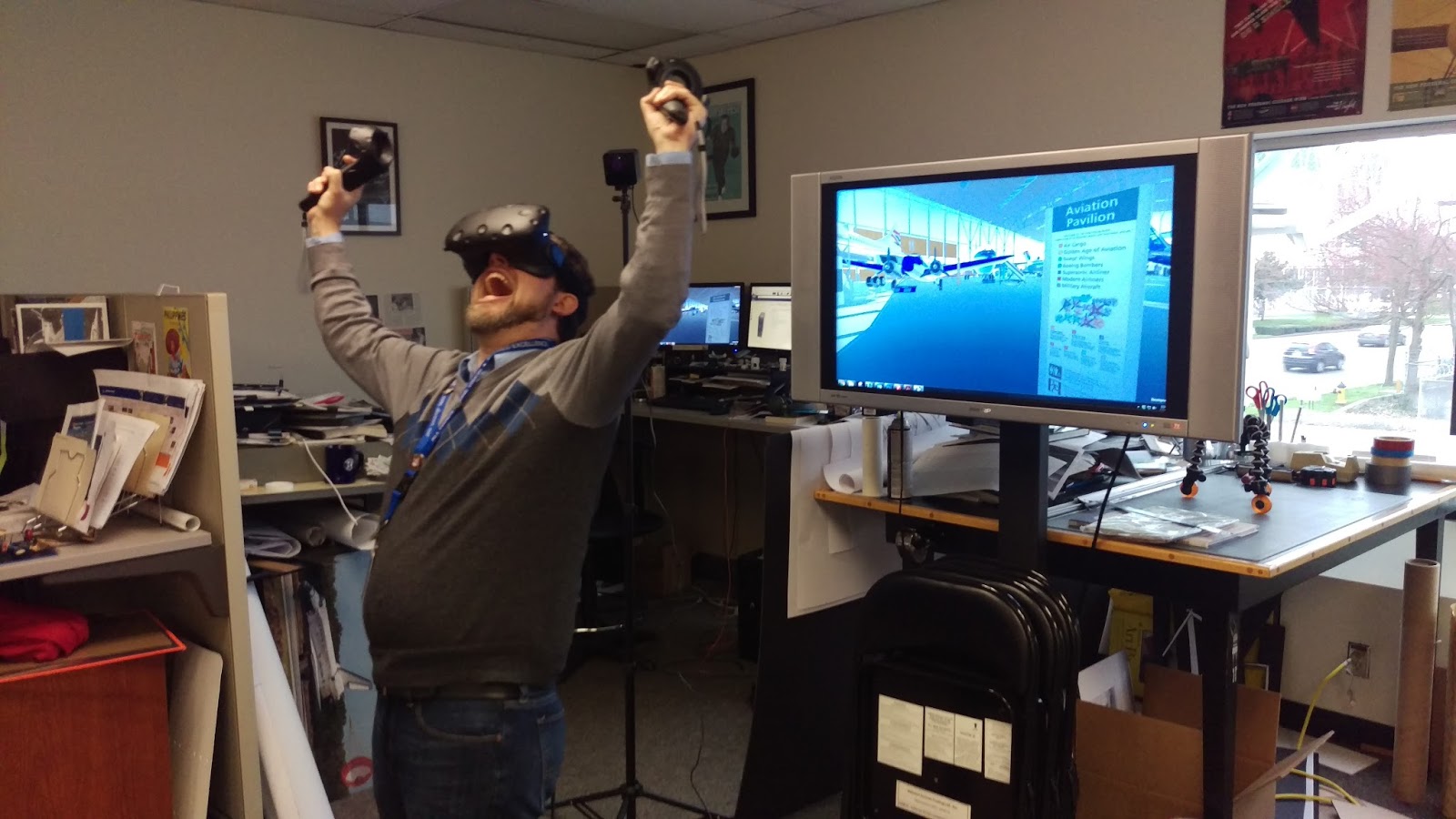

For the past six months or so, the exhibits department at The Museum of Flight has experimented with the use of virtual reality (VR) technology. We’ve tinkered with several different platforms ranging from the portable Google Cardboard to the room-sized HTC Vive system powered by SteamVR. Many of these and other VR technologies have great potential as both visitor engagement platforms and as exhibit development tools.

Our foray into VR really began last fall when the SteamVR team at Valve, a popular video game developer, reached out to introduce us to their work. They had a desire to move beyond their existing marketplace in videogames and Steam online (which is like iTunes for videogames) into virtual reality. Thefolks at Valve were interested in scanning unique spaces at our museum,namely aircraft and spacecraft cockpits and they plan to use the scansto craft custom VR experiences from these otherwise restrictedenvironments.

|

|

Third grade teacher Carlynn Nelson explores the Tilt Brush 3D painting simulator in the exhibits offices at The Museum of Flight. Photo credit: Peder Nelson/The Museum of Flight

|

During an introductory tour of Valve’s headquarters in Bellevue, Washington, our team got to tour some of their VR enhanced environments. These include the mundane—a virtual version of their own offices, and the spectacular—a Martian surface simulation put together from images taken by Curiosity, a NASA rover.

In exchange for permission to scan some environments at the Museum, the SteamVR team offered to supply us with three Vive development kits, including custom built computer CPU’s spec-ed to run their software. Further, when SteamVR goes live, scans from our museum will be included in the content available to customers, and we also can use the program as we please. The offer proved mutually beneficial, and so we jumped at planning next steps.

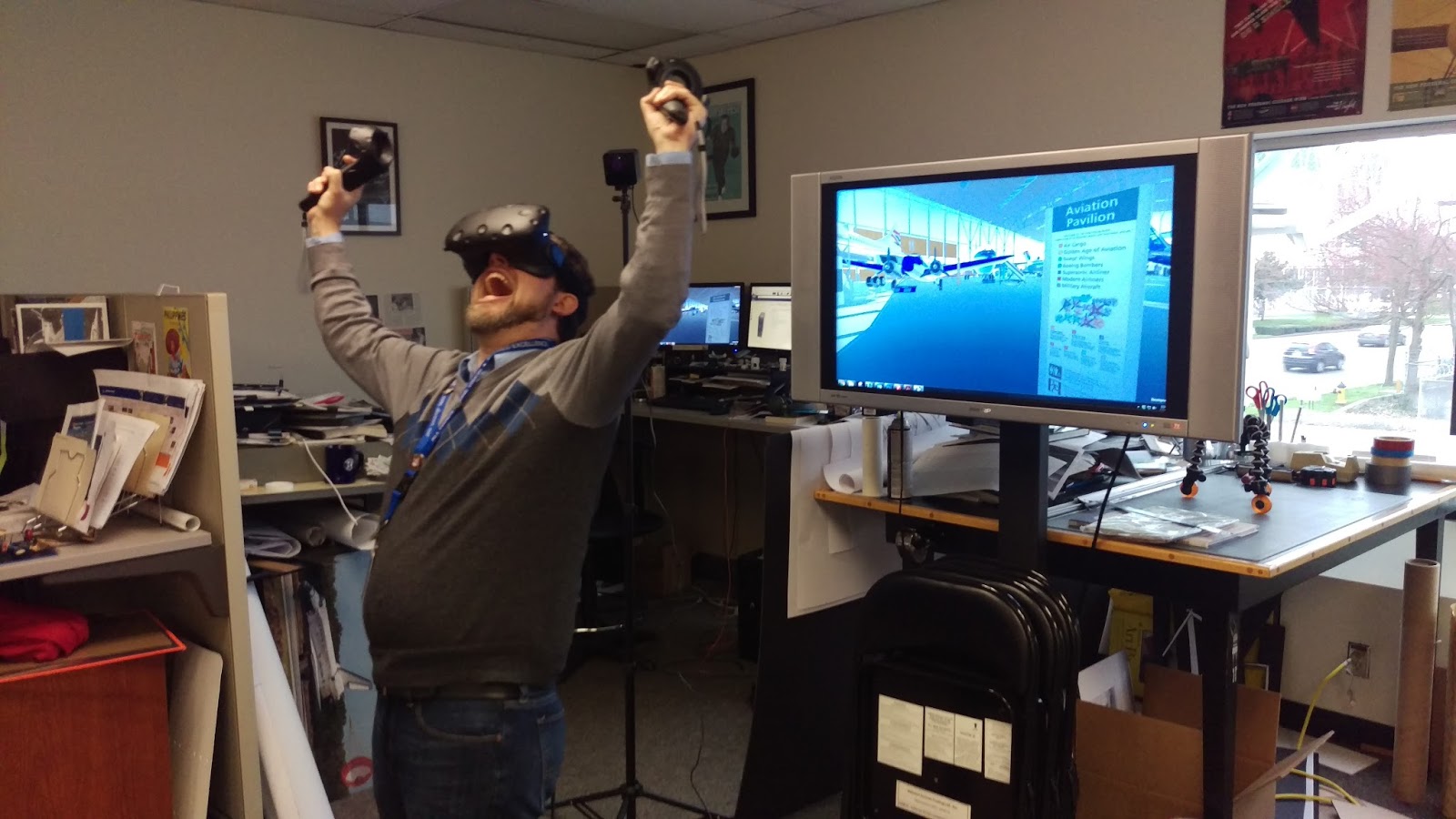

As promised, Valve delivered three development kits to our offices and we, in turn, conducted an initial planning tour of our first joint project, scanning the interior of the Museum’s Space Shuttle Trainer. Something that we were not initially aware of when we received our developer kits was that because of our work as an exhibits design studio we already had many of the resources and skills needed to begin experimenting with our own VR experiences. The Museum of Flight has designed museum exhibits for years using Trimble’s 3D modeling program, SketchUp. While tinkering with SteamVR, we found that we could export SketchUp models into the Unity3D game engine and publish them as a SteamVR-compatible environment. Suddenly, we could walk around our upcoming exhibits in life-size VR! The sense of depth conveyed by viewing 3D models in VR has proven especially helpful for getting a sense of human scale when working with very large artifacts like aircraft.

|

|

Geoff Nunn drops into a VR simulation of the Museum of Flight’s newest gallery seen on the screen behind him. Photo credit: Peder Nelson/The Museum of Flight

|

Not only did SteamVR allow us to test our own upcoming exhibits, but we were also able to import available 3D scans from other institutions. To date we have imported scans from the interiors of Castello di Miramare in Italy, a wooly mammoth skeleton from the National Museum of Natural History, and a full size Star Wars X-Wing model from SketchUp’s 3D warehouse.

During our Space Fest public program in November of 2015, Valve helped us with an initial public stress test of the system. At no additional cost to visitors, we offered free timed entry tickets to try out a custom VR experience for five minutes. This tour included the Mars surface simulation, an opportunity to walk around on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, and lastly a 3D painting simulation called Tilt Brush.

The response to the test run was overwhelmingly positive. The VR experience proved highly accessible to a wide range of visitors, including non-English speakers. Over the course of the event, we had participants in wheelchairs, and at least one young woman with Down syndrome share the experience. One of the more remarkable interactions occurred when an elderly visitor put on the goggles and suddenly yelled, “I can see!”… after 20 years of double vision that developed as a result of a brain hemorrhage. Something about the way the images were transmitted via the VR headset temporarily corrected her existing visual impairments.

Equally impressive was the response from Space Fest‘s invited presenters who work in the aerospace industry every day. A member of NASA’s Mars Curiosity team said that experiencing Mars in VR finally gave him a “sense of place” for the environment he had been exploring remotely for the past several years. A neuroradiologist who studies the effects of space on astronaut brains had a similar “wow” moment while exploring an environment assembled from publicly available CT scan data. The museum test was equally valuable for Valve, whose test audiences had previously been limited to the gaming community.

Since November, we have continued to tinker with the system in our offices, and just received our second-generation development kit earlier this month. We have not yet had a chance to coordinate the scan of the Shuttle Trainer with Valve, but hope to do so soon. Regardless, our initial forays into VR have given us a better understanding of the technology’s potential as a tool for both public engagement, and exhibit development in museums.