Chris Taylor’s commitment to helping his institution make traction in conversations about diversity, inclusion, and professional development led to the creation of The Department of Inclusion and Community Engagement (DICE) at the Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS). As the first director of DICE, Chris and his team develop internal and external strategies for diversity and Inclusion throughout the museums and Historic sites operated by MNHS. The goal of the department is to create a more inclusive organization, one where the state’s diversity is reflected within the staff and as well as the organizations’ internal structures. Today Chris shares some markers for institutions to follow during their drive to “Do Diversity” in our ever changing landscape.

Over the last few decades, museums have been challenged to “Do Diversity,” whatever that means. My experience is that this is often an unsupported mandate. As my colleague, Porchia Moore, wrote at The Incluseum, “diversity” is not even the word we should be using. Rather, inclusion implies that we recognize the value that diversity brings to our workforce, programs, products and services, and that we leverage diversity to make our organizations better. American museums have practiced systemic exclusion for more than two centuries. In order for museums to remain relevant institutions in the future, it is time for museums to learn how to practice systemic inclusion.

Back in 2008 the Center for the Future of Museums and Reach Advisors published Museums and Society 2034: Trends and Potential Futures, an article that illustrated the rapidly changing museum environment. Founding Director, Elizabeth Merritt then expressed the important need for museums reinvent themselves in order to keep pace. Much has been written about our field’s need to expand its work by reaching out to previously marginalized audiences and communities. Demographic trends show that continuing to create programming and exhibitions for primarily white middle class visitors is not sustainable. Museums must change in order to meet the needs of a broader section of society.

Museums typically “Do Diversity” through programming aimed at audiences from diverse communities. Many of these programs—though engaging—are created in Euro-centric organizations by staff who seldom represent the target community. Systemic inclusion calls for museums to look internally at their processes, procedures, policies and the cultural competence of staff.

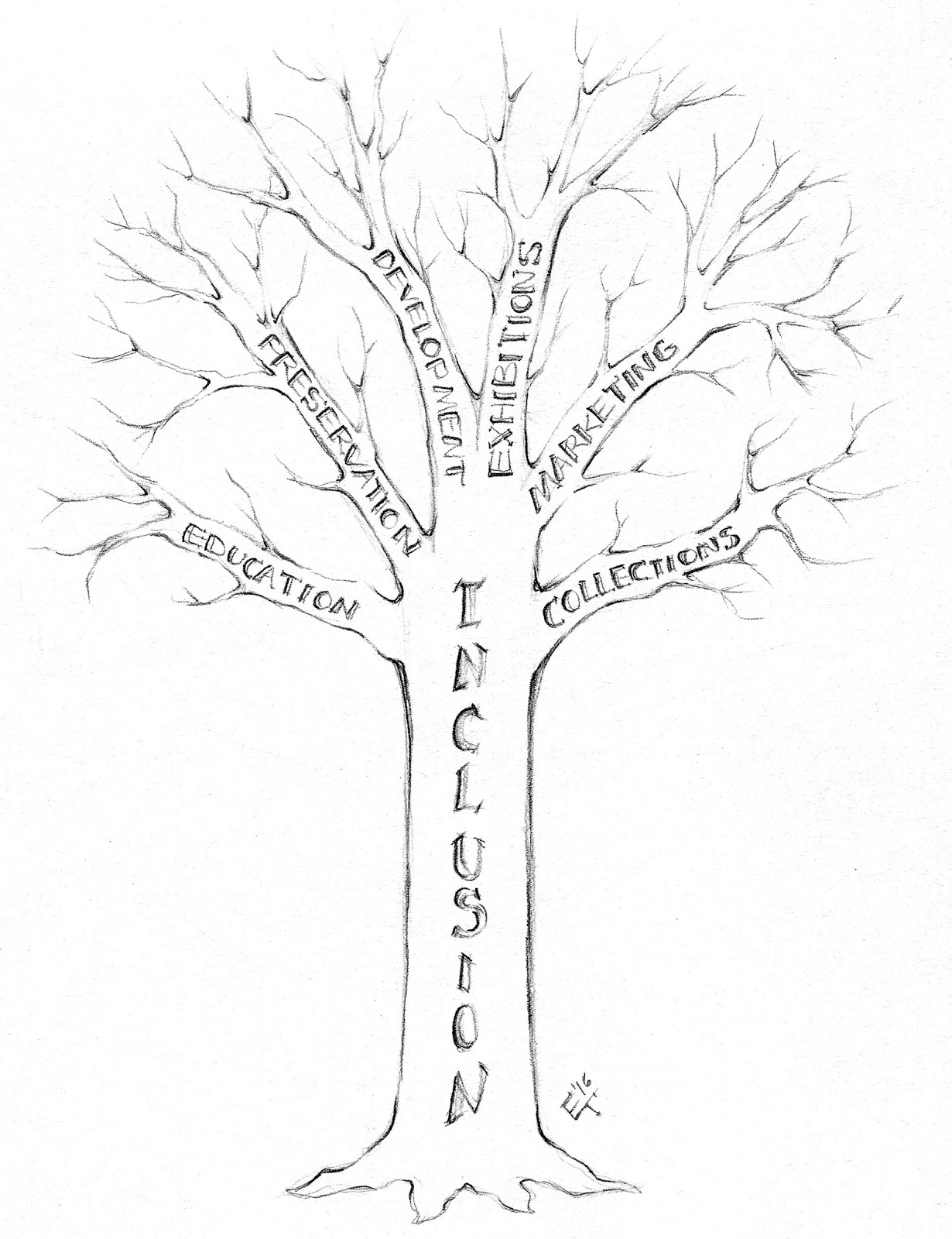

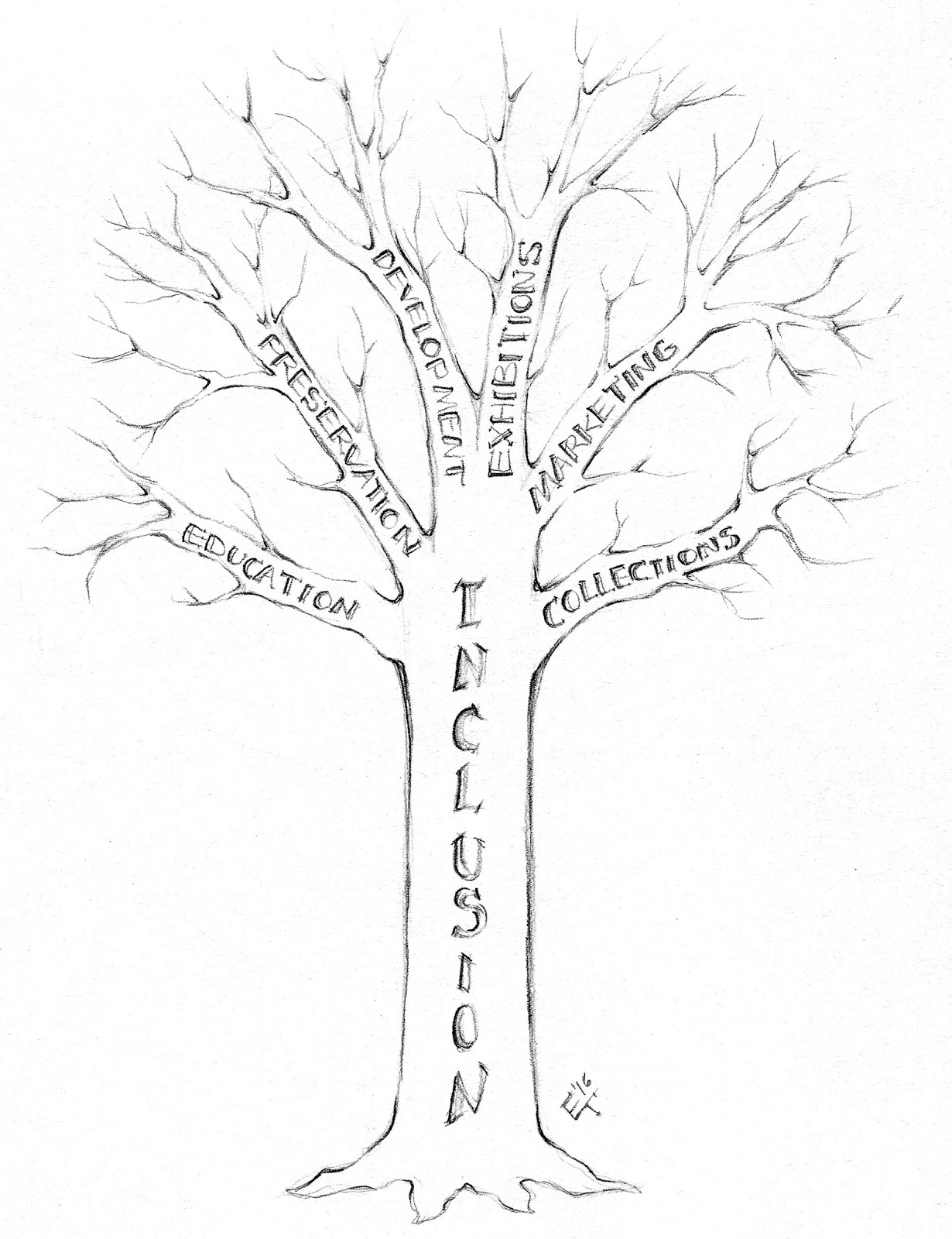

|

| Credit: Emily Taylor |

To use a metaphor of a tree, imagine if its branches represented the various functions of museums. There are branches for collections, exhibitions, preservation, education, development, marketing, etc. I argue that inclusion is the trunk of the tree and the strongest part that holds all other functions together. Understanding your organization’s trunk is vital for seeing how your staff think, act, plan, collaborate, and communicate. It resonates throughout the entire organization. Shifting to be more inclusive exponentially impacts the work across the entire museum. To begin this process, museums must focus on professional development, policies and procedures, as well as leadership.

Inclusion requires knowledge, skills, and abilities that are not wholly taught to museum professionals through training programs. Nor are these typically skills that staff can learn on the job. Albert Einstein’s quote, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results” rings true. We cannot expect for our field to do this work through osmosis. Museum staff need professional development opportunities. Through leading DICE, I see how our professional development opportunities with staff have encouraged:

- Increased cultural competence, including knowledge of the groups that have been marginalized by museums

- Greater awareness of attitudes towards diversity and inclusion in order to understand areas of personal biases and barriers

- More commitment from staff to build skills that allow for increased cultural flexibility and an ability to shift patterns of behavior toward being more inclusive.

In addition to increased cultural competence of staff, we also believe museums must examine policies and procedures for barriers to inclusion. Hiring practices, project planning and development, collections policies, and many other policies can be exclusive, or perpetuate the status quo. Often times, exclusive policies exist in museums not because current leadership and staff created them, but rather because many museum professionals continue to follow policies from days gone by. We need to examine our work and decide if obstacles to inclusion are allowed to perpetuate because we “can’t” or we “won’t.” If we “won’t” we need to ask why. If there is not a good answer, I encourage you to see if you can change your “won’t” to “will.” A word of caution though—it’s helpful to bring a Diversity and Inclusion professional in to review your policies and procedures. You may not be able to examine your policies in a new way until staff at your institution identifies their unconscious biases. We simply don’t know what we don’t know.

Leadership, it is your role to foster this change. You set the mission, vision, values and strategy for the institution. How inclusive are you? How much are you pushing yourself to understand the benefits of inclusion to your organization or how to shift culture? You should be on your own personal journeys, learning about inclusion practices in other fields that have had success. Are you attending conferences on inclusion in the workplace? An organizations culture is often read by examining its leadership. You must walk the talk. You set the tone and allocate the resources. And, ultimately if your espoused values are not congruent with your lived values, your organization will not change.

The inclusion gauntlet has been thrown before the museum field, but we are not building the necessary skills in our staff to meet the challenge. To sum up, the work related to inclusion is more internal than it is external. It is crucial that we continue community engagement efforts and programming targeted at various communities that historically have not been engaged by museums, but the biggest bang for our buck will be the internal work. To shift what museums are at their core to inclusive organizations will ultimately benefit all branches of the tree.

Comments