“The issue is jobs. You can’t get away from it: jobs. Having a buck or two in your pocket, and feeling like somebody.”—Studs Terkel

In the last two centuries, labor pivoted from the farm and workshop to the factory and the office. Now, as we enter the 21st century, work is again being radically reshaped by technology, culture and economic forces. Full-time work is fragmenting into the “gig” economy of Internet-powered freelance work. In the office, alt organizational structures are supplanting traditional bureaucracies. Many workers aren’t “in” at all—they are telecommuting or using co-working spaces instead. While high-value workers are demanding—and getting—flexibility, autonomy and imaginative benefits, technology is making the lot of part-time and low-wage workers even worse. Looking

forward, just as the assembly line created massive labor disruptions in the 20th century, robots and artificial intelligence will reshape the very nature of work, culture and our economy.

Everything about labor is coming into question, starting with when and where we work. Almost a quarter of all workers spend all or part of their day working from home, and that figure is even higher for people with a college degree. This is due, in part, to the ubiquitous Internet-connected devices that make it not only possible to work from anywhere, anytime, but create the expectation that a dedicated employee will do so. Talk of “work-life balance” is morphing into a dialogue about “work-life blending” as it becomes increasingly difficult to compartmentalize the two.

While a lot of work still gets done in a physical office, we are tinkering in significant ways with how that office is run. The dreaded ritual of the annual performance appraisal is coming under fire, both from unhappy managers and from researchers who demonstrate that negative feedback actually makes it harder for people to improve. To replace the annual review, mainstream companies like Adobe, Microsoft, the Gap, Medtronic, Accenture, Deloitte and the British Broadcasting Corporation are creating systems that provide continuous, futures-oriented feedback. High-performing organizations are focusing their management energy on supporting and rewarding their best employees, rather than on punishing the worst. Some companies are ditching traditional

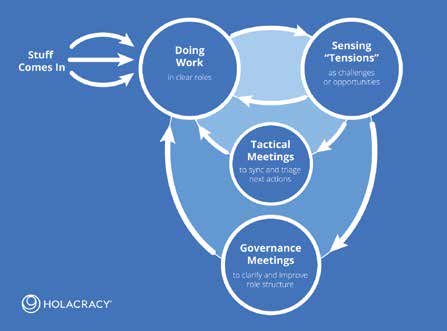

Some companies are ditching traditional topdown, hierarchical systems in favor of structures that foster more flexible and responsive work. This may be as simple as flattening the management structure to create fewer barriers between the CEO and frontline employees. Some companies, taking the lead from Internet startups, have established completely flat structures in which there are no job titles or assignments—just self-assembling workgroups. A few companies, most famously Zappos, are experimenting with holacracy—an egalitarian system that distributes power across teams via elaborately defined roles and highly structured meetings. And while wholesale adoption of these radical structures is still rare, their ethos and principles are filtering into the mainstream.

However they are structured, companies are seeking to retain their best workers by creating work environments that offer flexibility, autonomy and customized jobs. (See, for example, Enjoy—a startup electronics retailer that lets employees choose their own hours, pick their own schedules and manage their own training.) Some companies strive to create happy, supportive workplaces for philosophical reasons. Dan Price, the CEO of Gravity Payments who famously cut his own $1 million salary to $70K— the same as his lowest-paid employees—cited as motivation his belief that all workers deserve to make a living wage. But many managers are driven by hardnosed business considerations, based on growing evidence that there is a significant financial return on investing in happy workers.

Back in 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted we would move to a 15-hour workweek as prosperity and higher living standards translated into more leisure time. So far, the opposite seems true, with people working longer and harder just to stay in place. The current emphasis on comfy workplaces may contribute to this trend: If people have exercise rooms, nap pods, catering, even laundry service at work, why should they ever go home? (Some Google employees recently confessed they actually did live at work for a few months, to save on rent). There are some signs of hope, however. In Sweden, a 6-hour workday is increasingly common—with no drop in productivity.

Increasingly the world of work isn’t about full-time employment at all, however “full-time” is defined. While tech firms are doing almost anything to attract and retain highly trained, highly valued workers (both Apple and Facebook will pay female employees to freeze their eggs to keep them working during their peak reproductive years), low-wage, part-time jobs for relatively unskilled workers just seem to get worse and worse. Technology can foster abusive labor practices, as when fast-food chains and big-box retailers use real-time data analytics to schedule exactly the staff they need, when they need them. This is great for the bottom line, but makes it practically impossible for people, especially parents, to piece together enough part-time work to yield a livable income. (In 2014 Starbucks vowed to abandon “on-call” scheduling, acknowledging the destructive nature of the practice.)

which prides itself on “Helping the

World Work Better,” designs office

space around the individual needs

of staff. Photo: Alison Southwick for

Motley Fool

And the portion of work consisting of stable employment, full- or part-time, is shrinking. By 2020, 40 percent of the American workforce is projected to be comprised of freelancers, contractors and temporary employees. This gig economy isn’t just about low-skilled, interchangeable temps—it includes highly educated workers taking advantage of the Affordable Care Act and other systems to close the benefits gap between full-time and contract labor. In many ways, this is a win-win: Millennials prize flexibility and autonomy; employers avoid expensive, intractable infrastructure. But this bargain has a dark side as well: as our regulatory infrastructure lags behind, many gig workers are vulnerable to exploitation by companies seeking to maximize profits while offloading risks.

And the portion of work consisting of stable employment, full- or part-time, is shrinking. By 2020, 40 percent of the American workforce is projected to be comprised of freelancers, contractors and temporary employees. This gig economy isn’t just about low-skilled, interchangeable temps—it includes highly educated workers taking advantage of the Affordable Care Act and other systems to close the benefits gap between full-time and contract labor. In many ways, this is a win-win: Millennials prize flexibility and autonomy; employers avoid expensive, intractable infrastructure. But this bargain has a dark side as well: as our regulatory infrastructure lags behind, many gig workers are vulnerable to exploitation by companies seeking to maximize profits while offloading risks.

All these forecasts about how offices are organized and people are compensated presume that we have jobs at all. Given how rapidly robots and artificial intelligence are becoming more sophisticated, this is far from certain. Simple automation is replacing “pink-collar” positions like retail clerks, bank tellers and fast food workers. Robots have revitalized American manufacturing—boosting the profit margin of first the automotive and now the aerospace industry. Robots are being designed to flip burgers,

care for hospital patients, deliver packages—even perform surgery.

Automation is nosing its way into the office as well, in the form of intelligent assistants. “Chatbox” software is angling to replace personal assistants and customer service reps, promising to field both e-mail and phone calls. Management tasks can be automated too: prototype software dubbed iCEO can manage projects and people. As we approach true Artifical Intelligence (AI), we’re seeing an explosion of machine learning—the ability to use computational power to build on human processes, refine algorithms, detect patterns that humans would never be able to identify and predict future outcomes more accurately than human experts. These capabilities are

derailing solid professional careers like law, medicine and finance. IBM’s cognitive computing program Watson has become an ace diagnostician, able to analyze the vast medical literature real doctors can’t keep up with and recruit clinicians to fine-tune its results. Watson and his kin can interpret x-rays, prepare legal briefs and manage stock portfolios. All, its programmers claim, based on more information and less bias than its human counterparts.

People are pretty evenly split on whether this acceleration of automation is a good thing or a bad thing. Forty-eight percent of people in the UK are techno-pessimists who fear this trend will exacerbate income inequality and increase social unrest. The numbers seem to favor the pessimists: while adopting these new technologies can increase productivity by 30 percent in some industries—and save up to 90 percent of labor costs—over the next 20 years, robots and AI are projected to displace up to 47 percent of workers in the US, and 35 percent of workers in the UK.

But that’s displacement from existing jobs. The optimists believe these new technologies will simply create different kinds of work, even if we can’t foresee exactly what these new jobs will be. Just as computers created the highly lucrative field of software development, the rise of the robot could create jobs for people who can build and program robots (and maybe for robot ethicists as well). Programs like Watson, however powerful, may supplement rather than supplant their human counterparts, freeing them to do what humans do uniquely well—exercise creativity, intuition and compassion. (This thought would be more comforting if Watson and his kin weren’t also dabbling in creative endeavors like creating recipes and making videos, and intuitive endeavors like authenticating art, and if robots weren’t being programmed to provide empathic responses to their humans.) But would even a net loss of jobs be a bad thing? Keynes may have been wrong so far, but that doesn’t mean he may not eventually be right. If fewer jobs can be reconciled with broad economic prosperity, we will have to reconsider the fundamental purpose of work. Do we have jobs just to earn money? Or do we have jobs to live fulfilling, purpose-driven lives? And if the latter, once we have enough money to live on, do we need to get paid for our work? To a large extent, the crucial question is not who will work and get paid, but whether our national policies will favor the accumulation of wealth or its redistribution. Some people—an unlikely coalition of socialists,

But would even a net loss of jobs be a bad thing? Keynes may have been wrong so far, but that doesn’t mean he may not eventually be right. If fewer jobs can be reconciled with broad economic prosperity, we will have to reconsider the fundamental purpose of work. Do we have jobs just to earn money? Or do we have jobs to live fulfilling, purpose-driven lives? And if the latter, once we have enough money to live on, do we need to get paid for our work? To a large extent, the crucial question is not who will work and get paid, but whether our national policies will favor the accumulation of wealth or its redistribution. Some people—an unlikely coalition of socialists, libertarians and technocapitalists—advocate a guaranteed basic income as a way to end poverty, combat inequality and mitigate the disruptions of technology driven unemployment. While basic income has yet to be tried in the US (though one guy is lobbying for a pilot project in Detroit), the Dutch are trying out the concept in a handful of cities, including Utrecht.

What This Means for Society

The US is struggling with the role regulation can play in maintaining or recreating good middle-class jobs. Federal, state and city governments are grappling with whether to raise the minimum wage, and by how much. Labor issues are particularly difficult in a complex economic environment where any action can have an equal, opposite and unforeseen reaction. For example, while the Labor Department is considering tightening rules that let employers avoid paying overtime to millions of workers, others argue that employers will simply displace the cost by cutting benefits. Laws that support or subvert unions are particularly contentious, as unions, which championed workers’ rights throughout the last century, have seen their power erode in recent years.

The part-time, project-based, gig economy may require the invention of whole new regulatory structures. Entitlements are built around traditional employment—the rise of the gig economy may put significant strains on our healthcare support systems and on social security. Canada, Sweden and some other countries have established a new legal classification of “dependent contractors” to regulate conditions of employment for people working for sharing economy companies like Uber and Lyft. In the US, state and federal regulators are following suit, trying to craft regulations that protect workers from employers who try to minimize their costs by offloading risk and responsibilities onto their employees.

As automation and artificial intelligence continue to cut into both blue-collar and professional employment, we have to consider what role wealth redistribution plays in a society marked by massive unemployment or underemployment. Will unpaid work—artistic, creative, scientific, social—becomeformally valued for what it contributes to society? Will something like a guaranteed basic income become a right of citizenship rather than a stigma?

Jacqueline Brown, Noah Fischer and Arthur Polendo with Kenneth Pietrobono). Produced as part of Work It Out, Momenta Art Brooklyn,

2014. The Hidden Debt of an Art Fair, 2014.

What This Means for Museums

The overall state of the economy and the conditions of labor dictate the time and money people have to use museums. On one hand, the continued mutation of work into a 24/7 proposition may leave people even less time for leisure. On the other hand, flexible work hours, the rise of freelance and contract labor, as well as “sharing economy” jobs, create a large class of people with the flexibility to visit when it suits them.

The economy and the job market may also shape what people expect from museums in terms of education/training/opportunities. Just as libraries have adapted in recent decades to people’s need for Internet access, computer literacy training and job hunting assistance, museums may find themselves working farther down Maslow’s pyramid—helping people build their resumés, network and find productive work. As trainers, museums may specialize in serving as accelerators of higher-order human cognitive skills that are valued but not replicable by more intelligent machines.

Michael Govan, CEO of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, recently forecast the rise of the independent curator; museums may find themselves using more part-time and outsourced labor overall. Some believe the future of work will be characterized by fluid, temporary teams of skilled specialists, assembled to accomplish a specific task and dispersing when it’s done. That model, already being used in the movie industry, real estate development and new business ventures, may be preadapted to exhibit

production as well.

Museums have labor issues of their own. The use of unpaid interns is particularly controversial. While internships in for-profit companies are closely regulated, the Department of Labor has so far left a big fat loophole for nonprofits (stymied, perhaps, by how to distinguish between “interns” and the volunteers without which the charitable sector could not survive). But just because a practice is legal doesn’t mean it is ethical—and there is growing consensus among museum workers that unpaid internships are a disservice to our field. The US is currently enmeshed in

The US is currently enmeshed in debate about the ethics and economics of wages: minimum wage, living wage, the ratio between CEO and worker pay. These issues are tremendously important for museums as well, particularly as they seek to cultivate a more diverse workforce. There is a growing cadre inside the field, particularly among younger workers, calling for museums to “turn the social justice lens inward” and take a critical look at their own practices.

Museum Examples

The National Portrait Gallery in London and the Birmingham Museums Trust West Midlands have signed on to the voluntary Living Wage Certification system run by the Living Wage Foundation. This foundation was created by Citizens UK in 2011 to encourage employers to voluntarily pay wages pegged to the basic cost of living in the UK. They collect and share data that make the case for a living wage: the benefits to employers, including enhancing work quality, reducing absenteeism and improving retention; and the benefits to society, including strengthening families and alleviating poverty.

Early in 2015, members of the United Auto Workers went on strike against the Kohler Company. Local union members at the Milwaukee Public Museum issued a statement pointing out that “[p]ast struggles of Kohler workers, including the longest strike in U.S. history, have inspired the labor movement for generations. The current action by UAW 833 will play an important role in the post ‘right to work’ era in Wisconsin, showing labor unions once again how to bring back the fight and win for working people.” This is one example of how museums and their staff can help the public understand the current struggles of labor in the context of social and economic history.

Also in 2015, an informal coalition of museum activists founded #MuseumWorkersSpeak, dedicated to improving working conditions and other internal practices in museums and cultural institutions. They hold periodic Tweetchats, organize meet-ups and instigate conversations about museum labor practices

Museums Might Want to…

- Monitor the changing workforce in their communities and assess its needs. When is the most convenient time for people to visit the museum? What programs and services do they want? Perhaps there’s a need for co-working spaces—a niche some libraries are already stepping in to fill. Art museums could become the community hub for indies and startups in creative fields, science museums for sci/tech, children’s museums for education and family service programs. This shift could advance museums’ missions and generate revenue from underutilized space.

- Become early adopters of practices that create attractive (and high-performing) workplaces, including management structures that broadly distribute autonomy and authority. Museums can’t compete with the private sector on wages, but if they are willing to abandon outmoded practices, they can become the ultimate cool, creative place to work, so much so that the best and brightest are willing to sacrifice income to work in the field. This doesn’t have to mean ditching the org chart for a holacracy. Ninety percent of American workers feel underappreciated; improving the workplace can start with managers saying “thank you for a doing a great job” early and often.

- Confront economic inequities in our sector: the pay ratio between directors and front-line staff, the consequences of not paying a living wage and the debt young people assume in order to enter the profession. In addition to the need for museums to address this as a field, individual museums can assess their own internal practices, explore the values (ethical and economic) that could underpin reform, and change their policies and practices accordingly.

Additional Resources

You can find #MuseumWorkersSpeak on Facebook, follow them on Twitter (@MuseumWorkers) and read a bit about their work in the post “Unsafe Ideas: Building Museum Worker Solidarity for Social Justice” on the CFM Blog.

Performance-Appraisals.org curates a library of resources on alternatives to the annual performance review. The Diane Rehm Show also devoted an episode to the “Future of the Performance Review” (see the show’s website for transcript and recording).

Jacob Morgan (thefutureorganization.com) produces the Future of Work podcast and video series, exploring emerging business practices through interviews with leaders at some of the world’s most forward-thinking companies. Google’s

Google’s re:Work website (https://rework.withgoogle.com) offers guides, case studies and commentary on creating a better workplace, tackling subjects like combating unconscious bias, training managers to be coaches rather than critics, and providing professional development for staff.

Comments