Hi-it’s Sylvea….Today’s guest post considers the role that museums play in our on demand economy. Thomas Fisher is a professor of architecture, former dean of the College of Design at the University of Minnesota and a very frequent museum-goer. He offers a possible framework for establishing a way forward in this changing landscape.

|

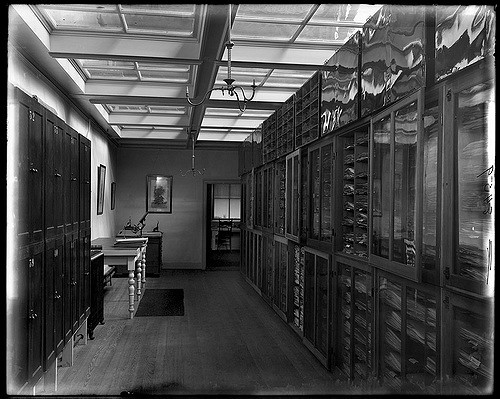

| The Field Museum Library |

What role does a museum play when we can download images of almost every kind of object or work of art on our mobile digital devices at any time? Such a question may sound ignorant or philistine, but we have to ask it of ourselves if we have any hope of sustaining museums – or any institution – dedicated to the storing, assessing, and conveying of human knowledge and creativity. Museums are not alone. The Higher education industry faces the same disruptive forces, with even more dramatic effect: Why sit in a lecture when you can get the same information faster and maybe even more accurately on your mobile device? And why come to a campus when you can now get a degree in some fields entirely online?

The pervasiveness of digital access forces us to re-examine why we have museums – or universities – in the first place. Our predecessors established such institutions so that people would have exposure to and inspiration from the products of human imagination and understanding in hopes that they, our visitors or students, might make their own contributions to the store of human accomplishment (or at least see their own lives differently and more expansively). That institutional role has not changed, even as the way in which people access images or information has. So how do we create a new kind of museum that complements rather than competes with the virtual “museums” most of us carry around with us on our smart phones?

One answer has involved museums making themselves more digitally friendly, enabling visitors to enhance their experience. While eminently sensible, that approach seems like a transitional solution, since it may be only a matter of time before the connection between the image and the information gets digitized across the full spectrum of artifacts. While there remains considerable value in seeing an object in person and in three-dimension rather than on a screen, the growing verisimilitude of virtual reality may take even that advantage away from bricks-and-mortar museums.

Another answer lies in Marshall McLuhan’s useful observation that every new technology turns the old one into an art form, an insight that might help us think differently about the future of the museum in the age of digital reproduction.1 Museums preserve artworks and artifacts, but in the digital age, they might themselves become an art form, offering experiences not available through any other means. What might that look like? As with art itself, these institutions must ensure that people will continually return to the museum, much as they do their mobile devices, to experience something new.

A weakness in the digital environment lies in its continually trying to assess what we like and to connect us to more of the same, which might work when trying to sell something, but which fails to offer people what they didn’t know they needed until experienced. For museums, this might mean moving away from chronological, geographical, or thematically related exhibitions toward the unexpected juxtaposition of apparently unrelated works within a collection. Asking the visitor to find the commonalities and differences among what’s on display, with enough background information, of course, to make the exercise fruitful and not frustrating could be another space of departure of curatorial work. Such seemingly random relationships may sound irrational or even an abrogation of curatorial responsibility. This approach, though, does what no digital environment can, which is to help visitors make creative connections among things and co-curate the experience they have in a museum on a continual basis.

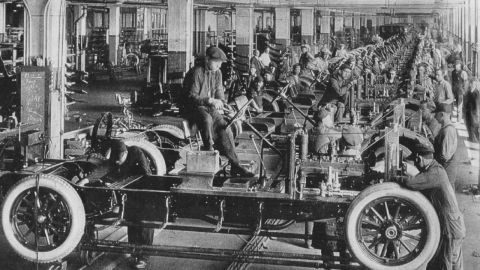

This might sound like a return to where many museums began, as warehouses of work of widely varying quality, stacked up the walls or in cases, with little information or explanation. But do not let appearances deceive. The serendipitous discovery of relationships among objects in a collection prepares museum goers for the world in which we all now exist, one in which creativity and innovation have become key to the success of both individuals and communities. This, in turn, implies a new social role for museums as not just the place for us to see works on display, but also a place to instill the habits of mind that will help us adjust to the rapid economic, environmental, and demographic changes occurring all around us. It may sound like heresy to some, but the works in museums – and museums themselves – in this light become means to an end rather than an end themselves.

How can you make this happen? Consider inviting the public to not just view work on display, but to re-imagine the museum in ways that will make it more relevant and revelatory. That, too, may sound heretical, but that is what the digital revolution portends: a future in which we are all producers and consumers of culture.

1. Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McGraw-Hill: New York, 1964, p. 38.