Since I’ve begun exploring the small but expanding universe of “museum schools,” I’ve discovered they come in many different flavors. Some are schools actually run in and by a museum (like the Grand Rapids Public Museum School). Some are schools that integrate local museums into their operations (such as the Museum School of Avondale Estates in Decatur, Georgia). Today Dr. Sally C. Krisel, President-Elect of National Association of Gifted Children and Director of Innovative and Advanced Programs at Hall County School System in Georgia, describes yet another variant: a school that behaves like a museum.

For decades educators and researchers have called our attention to the under-representation of economically disadvantaged, culturally different, and limited English proficiency children in programs for gifted students across our nation. There is, of course, the great personal tragedy of unrecognized and undeveloped talent; but, increasingly, this failure of traditional identification methods is becoming a matter of national urgency. Demographics are shifting in the United States. As a result, the numbers of low-income, culturally, linguistically, and/or ethnically diverse/different (CLED) students are increasing in our nation’s schools. We have become a nation where we can no long afford to fail to recognize or nurture the brainpower of any group!

|

| DVA Docemts |

The use of traditional identification procedures is most often cited as the reason for this continued failure to identify gifted children among underrepresented populations. However, another component of identification precedes the misuse or over-reliance on standardized test scores and may be at least as responsible for the underrepresentation of certain groups of children. This component is teacher advocacy, often the gate that gets a child to the assessment phase of the referral process. Training teachers to understand that typical characteristics of giftedness may manifest differently in high-potential and high-ability learners who are CLED, low-income, and/or in some categories of disability is part of the solution. But then we must also be committed to providing exposure to quality educational environments for high-potential students across all racial, ethnic, language, and economic groups so they will have opportunities to demonstrate and further develop their exceptional abilities.

In what ways might schools and communities offer a viable model for identifying and cultivating potential in students who have not had ample opportunities to develop their gifts, talents, and potential? I’d like to suggest that museum experiences are one important answer to those questions. And I’ll use the Da Vinci Academy (DVA) in Gainesville, Georgia, as one exciting example of this approach.

|

| DVA Cave Painters |

The most common model for museum schools involves partnerships between schools and area museums. Students visit the museums, benefiting not only from museum resources, but also from enriched curriculum planned collaboratively by their teachers and museum staff. Some partnerships even include schools housed at the museum. There is no doubt that these partnerships can enrich the learning for students from underserved populations, sparking wonder and igniting interests. DVA, however, takes a different approach to museum school education–it IS the museum!

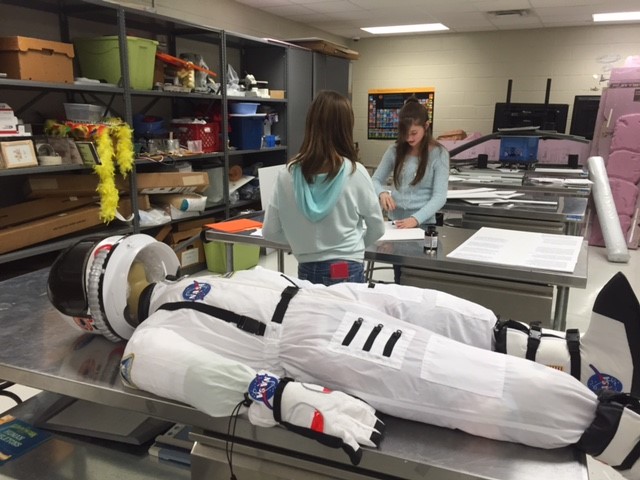

At DVA 240 gifted middle school students from Hall County, an economically and culturally diverse community 50 miles north of Atlanta, create three professional-quality exhibits a year, each based on a theme that interests them most from one of their integrated curriculum units. Students also continually update a museum annex that houses permanent displays like the largest triceratops fossil in the Southeast and a 40-foot mosasaur fossil. DVA students, who represent the diversity of the community, serve as docents for more than 1500 visitors a year — students of all ages, area seniors, state dignitaries, etc. Exhibits are interactive and visitor-centered, so students must determine the best ways to communicate with various groups. When decision making for exhibit content and format shifts from teachers and museum curators to students, the museum school approach develops students’ metacognitive skills, independence and confidence. Imagine the sense of personal power and self-efficacy that DVA students develop and how important this is for young adolescents, especially those who, due to circumstances beyond their control, e.g., poverty or their parents’ immigration status, may have felt powerless.

|

| DVA Museum Work Room |

But the positive impact of the DVA museum does not stop with the student researchers, artists, builders, curators, and docents. Many of those 1500 visitors are area children, two-thirds of whom qualify for free or reduced lunch. When these youngsters crawl into a simulated cave to learn about the art of prehistoric man, or dig for fossils, or watch a Chinese shadow puppet show in wide-eyed wonder, curtains are pushed back on their worlds! They are engaged in ways that spark interest, curiosity and a desire to know more. They are given chances to demonstrate abilities that might have been undetectable in a less stimulating environment, but now can be cultivated and nurtured by opportunity.

E. Paul Torrance, in his 50-year longitudinal study of individuals who had scored high on measures of creative thinking in childhood, was able to determine characteristics that were highly correlated to adult creative achievement. Several of the traits of “Beyonders,” as Torrance called them, bring to mind the kinds of experiences that museums can provide to facilitate the fulfillment of early promise. Those traits are: diversity of experience, openness to experience, love of work, and persistence – the same traits I see in students who attend and students who visit DVA.

Torrance concluded that one of the most powerful wellsprings of creative energy, outstanding accomplishment, and self-fulfillment seems to be falling in love with something – your dream, your image of the future. I wondered recently if I had caught a glimpse of a child’s dream when I spoke to a kindergarten student as he waited in line to get back on the bus after visiting the DVA museum. “So, what did you think?” I asked him. “Did you like the museum?” He looked up at me, his dark eyes sparkling, and said breathlessly, “This is the best day of my life!”

I watched that little Hispanic boy climb up the stairs of the bus that would return him to his school, one that is 95% minority and 100% F/R lunch, and I thought, “Oh, honey, I’m glad it was a great day, but I also hope it is the first of many days made richer, more meaningful, and more joyous by what you experienced. And I hope that light never goes out of your eyes.”

Reference

Runco, M. A., Millar, G., Acar, S., & Cramond, B. (2010). Torrance tests of creative thinking as predictors of personal and public achievement: A fifty-year follow-up. Creativity Research Journal, 47 (2), 361-368.

We actually just hosted a design-thinking workshop at The Museum School of Avondale Estates in Decatur, Georgia. They are an amazing group of people, very open to new ideas and a lot of Project Based Learning. I strongly recommend educators check them out. And check out the video of our workshop..www.vimeo.com/167057535