In Season 2 Episode 2 of the Museum People podcast, New England Museums Association director Dan Yaeger argues that all museums should be social activists, describing the oft-voiced museum ambition of being “places to convene discussions” as “weak tea.” In today’s guest post, Sean Kelley, senior vice president and director of interpretation, describes how the Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site in Philadelphia moved from neutrality to taking a position on criminal justice reform. Sean writes on prison museums at prison-museum-odyssey.tumblr.com.

Here at Eastern State Penitentiary, we are rewriting our mission statement to remove the word “neutral.”

We believe that the bedrock value that many of us brought into this field—that museums should strive for neutrality—has held us back more than it has helped us. Neutrality is, after all, in the eye of the beholder. At Eastern State, more often than not, the word provided us an excuse for simply avoiding thorny issues of race, poverty, and policy that we weren’t ready to address.

Most visitors to Eastern State are white. Most are middle class, and most are tourists to Philadelphia. Ten years ago I would have argued that leisure travelers don’t want to explore the complex and troubling root causes of mass incarceration. At the time we did commission artists to explore these issues at the physical edges of our property, but our tours and historic exhibits focused squarely on the past. Nobody complained.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleIn some small ways, I was probably right. Bipartisan support for criminal justice reform has grown dramatically in recent years. Ten years ago our staff was tiny, our resources modest, and our board of directors in transition. Perhaps we weren’t ready.

But mostly I was wrong. Development of our first Interpretive Plan in 2009 forced us to look more critically at our choices. Looking at a map of programming around the site, I had to conclude that our version of “neutrality” was mostly taking the form of silence. As a coworker said at the time, “Oh, we talk about race and the US criminal justice system every day…our silence tells visitors exactly what we think about it.”

I thought neutrality would create a safe space for visitors, but it was becoming clear that this space wasn’t safe for Americans who have experienced mass incarceration up close, within their communities.

We have tried to shift our focus to effectiveness and inclusion. We have found that many leisure travelers really will engage with these difficult subjects, but core elements of museum craft become more important than ever. Experiences need to be social, multi-generational, interactive, and accessible to visitors who don’t typically learn by reading alone. They need to genuinely value the wide perspectives and personal experiences of the visitors themselves.

In 2014 we built The Big Graph, a 16-foot-tall, 3,500-pound infographic sculpture that:

- represents the massive per capita growth of the US prison population over the last 40 years;

- compares the US Rate of Incarceration to every other nation on earth (we are highest by an enormous margin),

- divides nations into those that practice capital punishment and those that do not;

- tracks the consistent and disturbing racial disparity in our prison population over time.

Every visitor encounters The Big Graph. It concludes the main audio tour and is incorporated into every school tour. The text on the signage is direct and blunt. The audio tour asks “So why does the U.S. need to imprison so many people?” To our surprise, visitors consistently report that The Big Graph feels “neutral.”

In developing the companion exhibit, Prisons Today: Questions in the Age of Mass Incarceration, we faced a crossroads. We had dipped a toe into the pool of honesty about our perspectives, but we had maintained the illusion of neutrality. The new exhibit was shaping up to be a deep dive into issues of policy, race, enforcement, and outcomes. Were we really going to say “on the one hand….?” It felt patronizing.

There are too many Americans in prison. Our staff knows it, our advisors know it, our board knows it. And so we eventually united around a statement: “MASS INCARCERATION ISN’T WORKING.” That phrase opens the exhibit in 400-point block letters.

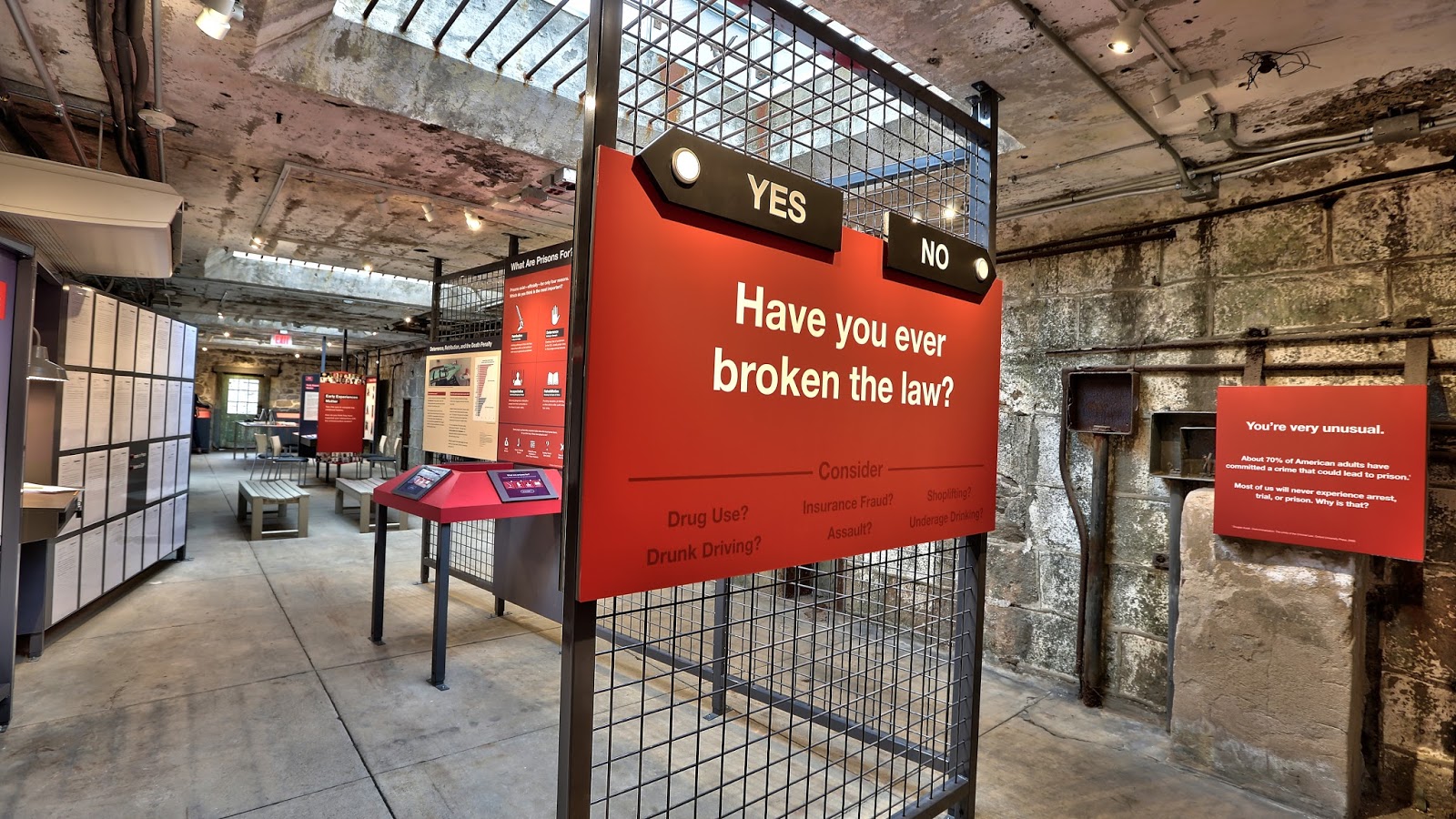

Nearby a seven-screen video tracks the political rhetoric that has driven criminal justice policy since the 1960s. The video ends with admissions of humility and compassion from a set of current political leaders, stressing voices from the political right such as House Speaker Paul Ryan. At a later point in the exhibit, visitors are forced to walk through one of two corridors, based on their willingness to admit if they’ve ever broken the law. Admitted lawbreakers are confronted with artist Troy Richards’ installation, asking if they see themselves as “criminals.” He invites these visitors to leave written confessions. He also mixes visitor confessions with confessions from men and women living in prison. Visitors try to guess which is which. They can’t.

If there’s a message to this exhibit, aside from the failure of our criminal justice system to justify the scale of its growth, it’s a call to empathy. Exhibit cases contain objects on loan from members of our tour staff who have been recently incarcerated. A beautiful and troubling film by Gabriela Bulisova tells the stories of six men and women impacted by the criminal justice system. A reading table includes “The Night My Dad Went to Jail” (written for children 5 – 8 years old). Visitors are invited to “Send a Postcard to Your Future Self,” using a digital kiosk to create personalized electronic postcards that will arrive in two months, one year, and three years. The postcards remind visitors of what they were thinking during their visit, and recommend ways that they can influence our nation’s rapidly changing criminal justice policies based on their responses to the exhibit content.

The journey to create this programming has changed our organization. Our board of directors now includes a scholar who studies race and incarceration and teaches inside prisons. It also includes a reentry professional who was himself incarcerated for seven years. [Full disclosure: like many museums, we lack still appropriate racial diversity on our management team; we know have work there to do.]

Our visitors—about 220,000 last year—aren’t expecting this programming when they arrive. Most want to see Al Capone’s cell or the site of the doomed 1945 “Willie Sutton” escape tunnel. I’ve grown to think that makes them the perfect audience to engage. Exit surveys conducted after The Big Graph’s completion reflect only 4 percent saying that the inclusion of contemporary content detracted from their visit. A full 91 percent of visitors reported learning something thought-provoking about today’s criminal justice system. The Prisons Today exhibit has only been open a few months, and summative evaluation isn’t yet complete. Press coverage and social media comments are encouraging.

Our audience has grown by more than 20 percent since we began addressing these complex and troubling aspects of American life. I once feared these subjects would suppress our attendance. I feared they would divide our board of directors and scare potential funders. I feared they’d harm staff morale, including my own. And I thought neutrality, whatever that meant, had to guide all of our programming decisions. I was wrong on every front.

Now I wonder what other misguided beliefs we’re leaving unexamined.

Sean, "neutral" is the opposite of "meaningful." The steps Eastern State is taking are striking a chord with visitors and creating moments of meaning and reflection that will translate for multiple cultures and resonate across a variety of life experiences. Helping people think, feel, and question is a primary job of museums.

Beth Tuttle

Co-Author, Magnetic: the Art and Science of Engagement

I think it's amazing that you're doing this. I visited in 2014 and having never visited a prison museum before, it made quite an impression. I'll have to come for a visit to see the updates. I'm glad to hear you are incorporating these contemporary and proactive elements to your museum, which engage visitors, as well as encourage activism and engagement within the community, and hopefully bring more reflection about the government's views and whether or not we, in the U.S. agree with them.

As a museum professional and a recent visitor (with my family including a 6-year-old and a 10-year-old who were completely engaged with all aspects of ESP), all I can say is BRAVO!

Courage is what makes institutions relevant and impactful.

three exhibits spring to mind: the Mapplethorpe show, the Art of the Motorcycle at the Guggenheim, and the Enola Gay exhibit t the Air & Space.

The Corcoran backing away from exhibiting Mapplethorpe's photography and the subsequent criminal indecency charges against the Cincinatti art museum and its director who did exhibit the work opened a whole new conversation in America. Some would argue that it just fueled the culture wars, but I think it's reasonable to say that the culture wars were fully engulfed, and this debate not only helped give gay voices a platform, but also shifted the conversation around AIDS in a way that eventually led to serious funding and research towards a cure.

The Art of the Motorcycle took an often-stigmatized category of industrial design, and presented it as would have befitted less-weighted areas of industrial design. Earlier exhibits looking at furniture and kitchen appliances had brought the mass-produced and commonplace into the discussion of art, but this exhibit touched upon a cultural taboo. People feared "Tattooed Mongol Hordes" descending upon the museum. Instead, the museum broke visitation records, and sparked conversations about stereotyping that are still playing out in the museum profession to this day as we create exhibits that draw people previously considered uninterested in museums.

The Enola Gay non-exhibit, on the other hand, serves as a cautionary tale for the profession. When the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum backed away from the backlash against a proposed exhibit that would tell not only the story of the airplane that dropped the first atomic bomb, but also the story of those impacted by the bomb, they chose path of "neutrality" that is exactly the kind of silent complicity that this article points away from. While the Air and Space remains one of America's most-visited museums, few visitors report having had a learning experience that challenged them or affected their sense of their place in our society. People go there to look at physically massive and impressive things, but don't come away with much more than a sense of having seen things they had read about before their visit. Is that how you would want people to experience your museum?

#TwelveOneFive blog is a collection of ongoing writing by #Ryan Michael Sirois that centers around the journey of self discovery.

King of Stars

This is such a good post. Thank you for sharing this information.

deportation lawyer in michigan

I assign this in our museum studies classes each year. It always generates thought-provoking conversations. Thank you for continuing to make it publicly available.