When the Alliance chose financial sustainability as one of three areas of focus for our new strategic plan, I gravitated to one of the hardest challenges of all: how can we help create financially sustainable models for supporting biological research collections? To tackle that challenge, CFM is partnering with the Ecological Society of America and the Peabody Museum of Natural History for a workshop to be held at Yale University this December.

At “FutureProofing Natural History Collections: Creating Sustainable Models for Research Resources” natural history museum curators and collections staff, current and potential users of collections, sustainability experts, management research specialists, and future studies experts (that would be me) will spend two days mapping the most effective ways to quantify and report on the value of research collections, and generating ideas for new economic models that translate this value into support.

I believe it’s harder to find new and better support systems for natural history collections than it is to find new economic models for other kinds of museums and other areas of operations. NEW INC and ACMI X are showing how museums can capitalize on space, expertise and reputation to create co-working spaces that generate new income streams (earned and philanthropic). Museum Hack has shown us that dynamic, irreverent, participatory tours can command a premium price. And I’m morally convinced that museums are poised to capture some of the $18.4 billion in federal support for primary education (not to mention comparable private funds) as we show we can provide superior learning experiences. While it will take much work to inject ideas and approaches such as these into the mainstream, they can at least give paths to explore.

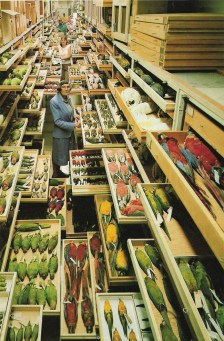

But research collections are a hard sell. Most people don’t even know we have them, and even fewer could name any tangible benefit they derive from shelves of fluid collections, frozen tissue samples, or a few hundred Cornell drawers filled with ticks. When pressed to make the case for how these collections benefit the public, our field generally trots out the same worn examples: identifying which bird hit an airplane; tracking vectors of disease and (more generally) documenting biodiversity. Not that these are bad things, but so far they haven’t been enough to make the case that either the government or individual citizens should pay for these benefits.

From a collections perspective, grant support has always been a dicey proposition. All too often support for the collections resulting from research are an afterthought, and museums’ responsibility to store and care for those collections, in essence, an unfunded mandate. This past March NSF announced it was putting an indefinite holdon their Collections in Support of Biological Research (CSBR) Program—one of the few sources of funds devoted to the care, organization, maintenance, and cataloguing of biological collections. Even though the CSBR grants collectively only represented about 0.06% of the NSF budget, they were widely seen as critical to the field.

NSF eventually restored funding, albeit on a biennial basis (effectively halving the funds provided), and it does continue to express active concern for the health and well-being of research collections –see, for example, its funding of this workshop. I’ve got to sympathize with NSF’s dilemma—well-managed research collections only ever get bigger. If they never develop sustainable income streams, how can the federal government (particularly in this economic and political climate) ever hope to keep pace?

I think there is a lot museums can do to make it easier for NSF, and other funders, to restore and grow support. At heart, the funding challenges faced by research collections are the same as those confronting all museums: how do we quantify and document the benefits we provide to society? How do we make a sound financial case that it’s worth it for some entity (whether that’s local, state or federal governments, private industry or other service providers) to pay for those benefits? What aspects of our resources and of our work have unexplored value for other users?