I’ve been following the work of Futurist Stuart Candy since the inception of CFM. The Sceptical Futuryst—his blog dedicated to “how we might feel about tomorrow”– is a staple of my scanning feed, and I’ve made good use of The Thing from the Future—an “imagination game” Stuart created with his colleague Jeff Watson. (“FutureThing” challenges players to create potential future objects, which is a perfect exercise for museum staff and museum studies students.) Stuart’s work recently collided with my world when he was selected as inaugural Fellow at the Museu do Amanhã (Museum of Tomorrow) in Rio de Janeiro, where he spent a month this summer as an artist-in-residence. I asked Stuart to share a first-hand report of this new museum with CFM’s readers. [This post is adapted from one published at his own blog in August.]

Housed in a spectacular building from Spanish neofuturistic architect Santiago Calatrava, the Museu do Amanhã attracted over a million visitors within nine months of opening in December 02015. This institution has a resonant rationale and an intriguing approach to what a museum can be.

|

| Photo via The Rio Times |

Today I want to share a conversation with Luiz Alberto Oliveira, a physicist with a PhD in cosmology, a former lecturer in the history and philosophy of science, and the Chief Curator of Museu do Amanhã. The following is an edited transcript of a conversation we had in Rio on July 6th. I am grateful to the Museum for hosting me, and of course to Dr Oliveira for taking the time to speak.

+++

Stuart Candy: What attracted you to this project?

Luiz Alberto Oliveira: It was daring. It had none of the usual boundaries or limitations, and it could have very important consequences for the practice or diffusion of science in Brazil.

We wanted to develop something from scratch, to discuss how a new kind of science museum could be devised.

We wanted to bring to the Museum of Tomorrow a different concept of time: the idea that in the present, you prepare, you make a different path to different possible futures. It’s not a river in the sense that you have one source and one end. You have, in fact, a delta of possibilities.

This is the main concept of the Museum, that tomorrow is not a date on the calendar, tomorrow is not a place where you will arrive. Tomorrow is a construction. Tomorrow is open to be built.

|

| Image via Museum Next. |

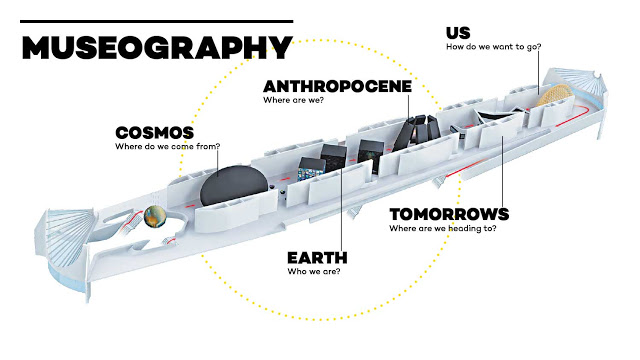

SC: And how does the organisation of the Museum impart this concept to visitors?

LAO: We settled on telling a story organised in five great areas. Why five? It is a dialogue with the architecture. Calatrava provides us with five roof undulations that roughly define the areas in which we set our museography.

So we came to the idea that the story should be made up of a sequence of great questions that mankind has always asked itself, so we could say in a very real sense that our content is questions.

Where do we come from?

Who are we?

Where are we?

Where are we heading?

How do we want to go; which values do we want to convey to the future?

This is the spinal column of the museum.

We use science content to illustrate these great questions, and the idea is that people come to realise that the future is not done, the future is in the making. It is in their hands, at least in part –– to collaborate in this future-building.

|

| Image via Museum Next. |

SC: This idea of a museum that isn’t about the past but is about the future, about choice, about ethics, does it have any precedents or parallels elsewhere in the museum world?

LAO: As far as we know, no, it doesn’t.*

SC: You made a very deliberate choice in naming this institution, “The Museum of Tomorrow”. Can you speak to that?

LAO: In the common sense, the future is far away.

But tomorrow is always here. Somewhere, at this precise moment, the sun is rising in the east. All the time, it is tomorrow somewhere.

This idea that tomorrow is always inside every now was what convinced us that it’s a “museum of tomorrow”, not a “museum of the future”.

SC: A museum about things that haven’t happened yet faces certain challenges. What are those challenges from a curator’s standpoint?

LAO: We established some trends which will shape the future some decades ahead: what science tells us about the possible scenarios for the climate, the changing of biodiversity, the growth of the population, the number and complexity of cities.

From all these you can forecast some reasonable scenario. But what about the unexpected that this cannot and will not take into account?

We did not want to become a museum of prophecy. That was the greatest challenge, the greatest danger, because people would come here and say, “Well, you’re telling us that the future will be this.” That’s not what we want to do. We want you to understand that the present is this, and the future? Well, there are many. This is the point; the futures are plural.

SC: A museum of questions rather than a museum of answers.

LAO: Yes, yes, precisely.

|

| Image via Museum Next. |

SC: When you talk about wanting to have a certain emotional impact on visitors, what’s the goal?

LAO: You want to take people away from their everyday perspective so they can understand that the world in which we live is much more complex, varied, surprising, full of wonderment, than everyday life which uses you, trains you, and tames you to become a useful citizen, a working citizen.

We want to provide a sort of entertainment; entertaining in the sense that it distracts you from your usual ways of thinking. To have different ideas, different perspectives. They just cannot become indifferent! If they leave the museum just as they came into it, we have failed completely. But if they are disturbed, well, that’s okay.

SC: What about the Brazilian context, and Rio in particular? Are there any special challenges or affordances for this project?

LAO: First, perhaps the fact that we are a museum open to the future, but we are sitting in the very heart of Rio de Janeiro’s history. You can see all the landmarks of centuries around us. This heart of the city was abandoned for decades. So we are in a way a flagship of this new moment, of this new period of the city’s story.

I think the Cariocas, the people of Rio, understood that. They took possession of the renewed plaza, because you know, it’s theirs.

On the other hand, we have the very difficult condition of the country at the moment. The legitimate government was overthrown by a parliamentary coup, and a bunch of gangsters took power for themselves. So we are in a struggle for democracy itself, the very core of democracy, which is election.

But many people tell us that the museum is a counterpoint to this situation. This is something inspiring. We wanted to inspire people––but I did not know that it would be in this sense, that we became a symbol of a better future for the country.

|

| Image via Museum Next. |

SC: The invitation to regard the future as shapable and as plural is a deeply political position.

LAO: Certainly. You cannot deal with conviviality, with living together, without politics. It’s impossible. So in fact, we are a political museum. We cannot say that as a slogan of the museum, because people would not understand in that sense. They would think that we are engaging in this or that political party, which is not our intention.

SC: I see vast potential not just in this institution, but in this category of institution, a kind of museum that is needed everywhere. There is a need for effective invitations to people, to draw out their vision for how things could be different.

LAO: I understand and I agree completely, because I think this is a path for renewing democracy itself.

* Stuart plans to revisit the question of the Museum of Tomorrow’s conceptual cousins in posts to come. You can use the comments section, below, to suggest related museums he may want to include in that coverage.

Fascinating! I think a trip to Brazil is in my future…

This place is not a museum, no way. If anything, it is Rio de Janeiro's Municipality showing off to tourists on the city's expense.