One of the things I love best about social media is its power to connect me with strangers. When Jon Christensen tweeted, back in November, about a panel exploring extinction and de-extinction to be held at the La Brea Tar Pits, I tweeted back inviting him to blog about the talk for CFM. (Jon’s an adjunct assistant professor at the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability as well as a co-founder of the Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies (LENS) at UCLA.) I was interested in the event because the organizers promised to explore “How museum exhibitions, images and films about them shape science, laws and policies to protect endangered species”—a good fit for CFM’s work documenting how museums can change the world. Also, as a futurist married to an ecologist, I’m fascinated by the ethical and practical controversies surrounding efforts to revive extinct species.

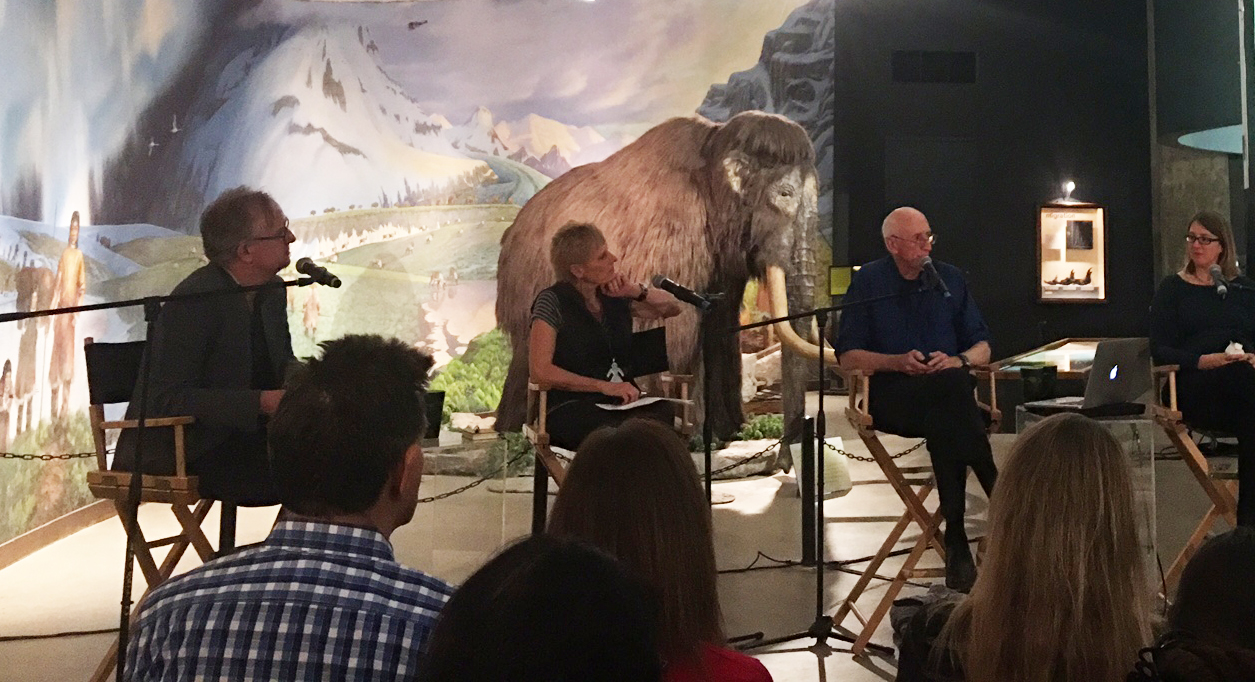

A shaggy woolly mammoth lurked forlornly in the background behind us, as I moderated a panel discussion at the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum recently with Stewart Brand, an advocate for “de-extinction” of the woolly mammoth and other species, Ursula K. Heise, author of the new book Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species, and Emily Lindsey, the dynamic new assistant curator and excavation site director at La Brea, which is part of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

|

| Panelists discuss extinction and de-extinction under the jaundiced gaze of a woolly mammoth at the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum in Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of Evelyn Wendel. |

It’d be hard to imagine a better setting for talking about extinction, endangered species, climate change, and our hopes and fears for the future. We were also surrounded by skeletons of extinct saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and giant ground sloths, all found in the tar pits. These specimens from the past seemed to crowd around the audience for a lively discussion about the future of this very place and the planet in the face of tremendous changes in climate and ecosystems.

As Lindsey pointed out, the tar pits are an archive of global change from the last Ice Age to the present, a period in which dramatic changes in climate and human influences on the landscape and species intersected. And the La Brea Tar Pits don’t just document the demise of the charismatic megafauna that capture most of the attention in the museum, but also have yielded millions of specimens of more than 600 other species of vertebrates, insects, and plants that have lived here over the past 50,000 years, many of which have adapted and survived into the present.

The challenge for the museum is how to make that amazing archive, which is still being unearthed daily in ongoing excavations, and the stories it tells relevant to today’s urgent conversations about climate change and the possibility that we’re living through the sixth mass extinction on Earth, this one caused by us. The panel was part of the museum’s efforts to experiment and explore the role it can play in the future, and it was co-sponsored by UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, where Heise and I are on the faculty.

And who better to kickstart such a conversation than Stewart Brand? Founder of the Whole Earth Catalog and the Long Now Foundation, Brand is an advocate for expanding our thinking to ten-thousand-year timeframes, for the future as well as the past. Brand presented his fantastic-sounding, but utterly serious, and scientifically possible scenario for recreating a woolly mammoth using cutting-edge gene editing techniques. The plan is to take DNA recovered from mammoth specimens in Siberia and place it into elephant embryos, tinkering with combinations until we create a reasonable facsimile of a woolly mammoth that can play a role in “rewilding” appropriate habitat in the far north. The same gene technologies could be used to turn a band-tailed pigeon into a passenger pigeon, he said.

Lindsey was skeptical. There have been such enormous changes in the habitat that these species depended on, she said, that it’s hard to imagine them thriving as wild populations. Instead of trying to recreate lost species, we might be better off using the lessons of the past to figure out how living species can navigate a landscape that is being transformed by humans and climate change.

Regardless of whether “de-extinction” ever succeeds, said Heise, it’s a fascinating narrative twist, the obverse of the gloom and doom narratives of loss that dominate the ways we generally talk about endangered species. Brand’s vision is a hopeful and creative one, she said, and it holds out promise that we might redeem ourselves in some ways from the environmental damages wrought by humans.

Museums, along with books, films, other media, and arts, have all played enormous roles in shaping what Heise calls the “cultural imagination,” which is in many ways just as important as the actual science of endangered species and extinction. And museums, as well as other cultural institutions, can play important roles in imaginatively refashioning the ways we think about conservation, too.

The Natural History Museum’s Urban Nature Research Center and citizen science projects are helping to change the way Los Angeles is seen, from the wasteland it is imagined to be in popular culture to the biodiversity hotspot it is in fact.

The Natural History Museum has an official statement on evolution, and it is now researching a statement on climate change. Several other natural history museums have already issued such statements.

Arguably more important than an official statement—which, to be sure, can help the museum work out its position—is the work of opening up the museum for conversations about living on a changing planet. Research has shown again and again that hammering people with facts and positions does little or nothing to change minds, let alone open hearts.

On the other hand, providing a window into the work of science at the La Brea Tar Pits—part of the museum’s mission is to “inspire wonder and discovery”—and at the same time, a place to explore the stories we tell about our role in this changing world—might just be the ticket the museum needs to deliver on the promise of the third part of its mission: inspiring “responsibility” for our “natural and cultural worlds.”

You can listen to a recording of “Extinction! Fear and Hope at the La Brea Tar Pits” at nhm.org/lectures.

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

Thanks for this report.

Readers interested in a fairly comprehensive review of the current state of the science, technology, and ethics of de-extinction and its potential consequences for life on earth will enjoy M.R. O'Connor's thorough and thoughtful publication, RESURRECTION SCIENCE: Conservation, De-Extinction and Precarious Future of Wild Things (St. Martin's Press). O'Connor explores the moral dimensions of current researches aimed both at preserving existing species and recreating ones that have already perished as a consequence of human activity.