“It’s easy to imagine that a system like mass incarceration can’t be dismantled. The same was said about slavery, the same was said about Jim Crow. —Attorney and author Michelle Alexander

President Barack Obama gave considerable attention to criminal justice reform during his two terms, commuting the sentences of dozens of nonviolent drug offenders, presenting his vision for the future of the criminal justice system to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and becoming the first sitting president to visit a federal correctional facility. Under his leadership, the White House’s Data-Driven Justice initiative fostered the recognition and replication of successful state and community-based efforts.

While the election of President Donald Trump may have signaled a shift away from federal reform, there are signs that the momentum of local reform will continue. In the 2016 election, voters in Oklahoma reclassified minor drug possession and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors, and channeled the cost savings to mental health and drug treatment services. Voters in New Mexico supported changing the state constitution in order to prevent detention of defendants solely due to their inability to post bail. Voters across the country opted to legalize recreational use of marijuana or facilitate medical applications of the drug. Many communities elected reform-minded district attorneys who campaigned on platforms of less incarceration and less punitive sentences.

What this means for society

Criminal justice reform has been prioritized by the international community as part of efforts to help postconflict societies reestablish the rule of law. These efforts acknowledge reform must be grounded in respect for human rights and reshaping public attitudes toward law enforcement as well as specific changes to policing and incarceration.

Many Americans believe that criminal justice and mass incarceration are the civil rights issue of our times. In the United States, blacks are much more likely than whites to see racial bias in the justice system, and for good reason: the overlap of poverty, race, and incarceration is hard to overstate. Indeed, these issues are essentially facets of the same problem, since the criminal justice system as currently constituted perpetuates racial disparities in wealth, education, and opportunity. The US criminal justice system has been used for many decades as a substitute for a comprehensive system of support for people in need of medical treatment for mental health issues or drug dependence. See, for example, how a range of laws about public behavior and the use of public space effectively criminalizes homelessness.

Formerly incarcerated men and women experience high levels of unemployment, which particularly injures women and families, as feminized professions such as retail and caregiving routinely require criminal background checks. The direct and indirect costs of becoming entangled in the justice system weigh most heavily on the poor, often miring families in ongoing cycles of debt. It also damages the economy as a whole: economists estimate that such barriers to employment reduced the US GDP by $78–$87 billion in 2014.

Mass incarceration has created what has been called “felony disenfranchisement”: 6.1 million Americans are unable to vote due to state policies barring felons from voting. Twelve states carry lifetime voting bans for men and women with felony convictions. Permanently removing the right to vote from people who have first-hand experience with the injustices of current policies makes it that much harder to enact reform.

Youth incarceration is particularly problematic, as early imprisonment has lifelong effects on a young person’s education, well-being, and attainments. This practice also disproportionately affects people of color, who are more likely to be charged and more likely to get harsh sentences. This inequity reflects deeper attitudes in our society that emerge as early as preschool, when teachers’ unconscious bias leads to black boys being disciplined at higher rates than their white and female peers, and sets the stage for what has been dubbed the “school to prison pipeline”—a system in which zero-tolerance policies in education funnel children out of school and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems.

Deconstructing the US system of mass incarceration will require deconstructing the economy that has grown up around it. Many municipalities rely on fines from law enforcement as a major source of revenue, often selling these debts to private businesses that increase the debt via fees and interest. So called “profit-based policing,” which incentivizes overenforcement in mostly poor, politically disempowered neighborhoods, helped create the tensions that led to widespread protests after the police killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. (Court fines and fees are Ferguson’s second largest source of income.) In 2014, the private prison industry was a $4.8 billion business with profits of over $629 million, housing nearly 20 percent of federal prisoners and 7 percent of state prisoners. Involuntary servitude of prison populations is legal in the United States, and incarcerated workers are often forced to work for little or no pay through in-prison business or via “convict leasing” to external for-profit companies. The pricing and profits of companies such as AT&T, Victoria’s Secret, McDonald’s, and BP (British Petroleum) are, effectively, subsidized via incarceration.

What this means for museums

Museums’ communities are being buffeted by the economic, cultural, and political fallout from current inequities in the justice system. Increasingly, museums are being called on to play a role in addressing these tensions through serving as venues for dialogue, as places of healing, or by acting as advocates for social justice.

Museums can help society reexamine the history and current practice of justice in the United States. They can create exhibits and programming that respond to current and local events and shape the discussion of how to move forward.

Even as museums become more conscious of the need for security in the face of domestic and international terrorism, they need to be aware of the message that security sends to portions of our communities. Adding officers and bag checks can make some people feel less secure, not more.

As the museum field commits to diversifying its own workforce, it needs to consider the effects of excluding people with criminal records. Besides disadvantaging a population that needs employment opportunities, this treatment also impedes progress toward racial diversity, given the disproportionate number of people of color with criminal convictions.

Museums might want to…

- Address issues related to criminal justice explicitly in their exhibits and programming.

- Create ways to connect the public with incarcerated or formerly incarcerated people in order to promote empathy and foster understanding.

- Go beyond neutrality and take a position on the negative effects of current systems and the need for reform.

- Examine their own hiring practices, especially with regard to criminal background checks. The federal government and over 150 cities and counties in the United States have adopted so-called “Ban the Box” policies and “fair chance” employment laws barring employers from asking about a candidate’s criminal record at the beginning of the application process. Even if a museum operates in a city or county that does not ban the box, it can voluntarily foreswear using previous convictions to weed out job applicants early in the search process. Museums can also choose to proactively assist formerly incarcerated people by providing job training and experience, and encouraging them to apply for museum positions.

- Revisit their own security practices, with awareness of how their policies and procedures may intimidate or exclude some audiences.

Museum Examples

In creating the exhibit “Prisons Today: Questions in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” staff of the Eastern State Penitentiary museum shifted from their historic position of neutrality on the subject of prison reform. The exhibit opens with the phrase “MASS INCARCERATION ISN’T WORKING” in 400-point font; videos feature bipartisan statements on reform; visitors are asked to admit whether or not they have broken the law, and, if so, to leave a written confession. Staff see the exhibit as a call to empathy, reminding visitors of how they can influence the future of criminal justice in the United States.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) is identifying, documenting, and memorializing sites of more than 4,000 lynchings of African Americans across 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950. EJI plans to create a memorial and museum called From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, opening in 2017. The names of over 4,000 victims will be engraved on concrete columns representing each county in the United States where these lynchings took place. Counties across the country will be invited to retrieve and display a duplicate of their column. These installations will highlight the historical connection between these lynchings, the current application of the death penalty, and mass incarceration.

Constitution Hill in Johannesburg, South Africa, is a museum sited in a former prison that incarcerated, among many notable inmates, civil rights activists Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi, Joe Slovo, Albertina Sisulu, and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. The stories the museum tells remind visitors how the justice system can be used to enforce oppression and maintain the status quo, but also demonstrate the power of activism. This “living museum” is also home to South Africa’s Constitutional Court, the highest court in the land, charged with protecting the rights of all citizens.

At the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, RAISE: Responding to Art Involves Self Expression is an alternative sentencing program that works with high school students referred to the museum by the Berkshire County Juvenile Court. Over a five-week period, participating youth engage in group meetings that include writing and self-awareness exercises, gallery talks, and the use of art as a catalyst for examining their lives and their potential. Since its inception in 2006, the program has served over 120 youth and documented significant improvements in student behavior and in their attitudes toward themselves and toward art.

Further Reading

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander. The New Press, 2012. Alexander documents the effects of the US criminal justice system, arguing that “we have not ended racial caste in America; we have merely redesigned it.”

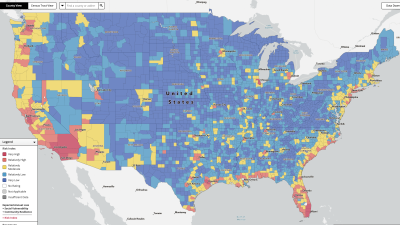

The Sentencing Project has been working on US criminal justice issues for 30 years, promoting reforms in sentencing policy, addressing unjust racial disparities and practices, and advocating for alternatives to incarceration. Their website (sentencingproject.org) provides a number of fact sheets and Web tools, including state-level data on criminal justice.

The Equal Justice Initiative is committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society. Their website (eji.org) includes videos, reports, and news briefs on racial justice, children in prison, mass incarceration, and the death penalty.

Skip over related stories to continue reading article

Comments