I’m going to ask you to bear with me as I engage in some deep, extended geeking about business models in coming weeks, via a series of essays and guest posts exploring changes in business and philanthropy that are reshaping the niche museums occupy in society. First up is an exploration of benefit corporations: what they are, how they impact museums, and how they may shape the future.

One challenge facing the whole nonprofit sector is that the distinction between our work and that of for-profit businesses is increasingly fuzzy. This is, in part, our own dang fault. A lot of what museums do to earn money is indistinguishable from for-profit counterparts: we sell stuff in our shops, we run restaurants, we rent out our space for weddings and graduation parties. Many of the distinctive mission-related things we do (conducting research, preserving collections) goes largely unseen and unknown. Many of the visible mission-related things we do go unappreciated (For example, Reach Advisors reports that only 12% of the American public thinks of museums as educational.)

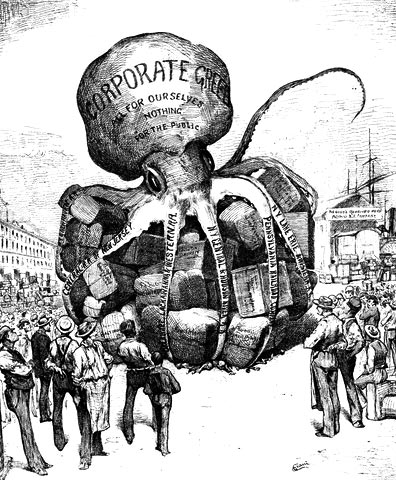

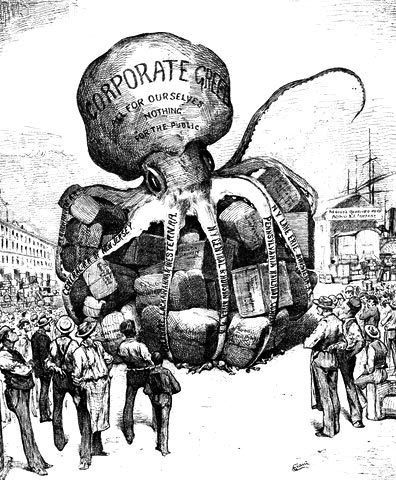

|

| Not all for profit businesses are in it “just for the money” |

Part of this fuzziness comes from the way the for-profit sector behaves as well. I’ve never bought into the dichotomy of “for-profit: money grubbing, bad” v. “nonprofit: altruistic, on the side of angels, good!” I know plenty of independent business people (including many museum consultants) who choose to do what they do because they believe their work makes the world a better place. And many of these people make decisions based on more than the bottom line. Sponsoring the local teen soccer team may get a business’ name on their jerseys, but the The Hole Thing probably spent more on the uniforms than they get back from a resulting uptick in donuts sales.

Then there’s the fact that some high profile museums are for-profit entities: Biltmore, a huge historic house/site in North Carolina; the Museum of Sex in NYC; the Dallas World Aquarium; the City Museum in St. Louis; and Graceland, to name a few. Frankly, people may not know or care whether a museum is nonprofit or for-profit. Both the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland and the International Spy Museum here in DC started out as for-profit entities, before eventually applying for 501(c)3 status. Even when they were for-profits, I knew of people who volunteered their time and donated objects to those museums. And many for-profit exhibit venues are indistinguishable from museums, to the public at least, especially when they host exhibits such as plastinated human bodies or animatronic dinosaurs.

Now there is a new trend further blurring the nonprofit/for-profit boundary: the rise of hybrid legal structures. The most prevalent of these is the benefit corporation, a type of for-profit corporation that is legally obligated to create material positive impact on society and the environment in addition to financial profitability. Shareholders hold the benefit corporation accountable for its financial, social AND environmental performance. This provides the benefit corporation with legal cover for making decisions about operations that may reduce the financial return for investors—things like paying a living wage, sourcing materials from sustainable sources, or supporting minority-owned businesses via their supply chain.

In 2010, Maryland became the first state to pass benefit corporation legislation, and now this legal structure is authorized by 30 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. As of April, 2015 there were over 2,100 active benefit corporations in the US. From this modest start the movement is gaining steam nationally and internationally. Italy has authorized a similar kind of entity, Società Benefit, for the whole country.

Why doesn’t an organization devoted to fulfilling a social or environmental mission simply incorporate as a nonprofit? I’ve asked that question of a number of people who run benefit corporations, and they usually flip the question, asking “Why would we want to be a nonprofit?” They often see nonprofit governance as problematic and inefficient, and grant funding as coming with too many strings compared to relatively small awards. Also, nonprofit status itself confers fewer benefits than it used to: payments in lieu of taxes are increasingly common, and tax reform may well shrink charitable donations in coming years.

Perhaps most compelling is this argument: if you have a choice between being a donor, and producing a social good with your money, or being an investor in a company that produces a social good AND gives you a return on your investment, which would you pick? Nonprofits may pride themselves on transparency and accountability, but they often do a sloppy job of quantifying their social or environmental impact. Benefit corporations are required to use comprehensive, credible, independent, and transparent third-party standards to certify their social and environmental performance.

The rise of benefit corporations is being driven in part by established philanthropies. Funders such as the Rockefeller Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and Omidyar Network (a philanthropic investing group) are growing increasingly impatient with the seeming inability of billions of dollars in philanthropy to actually solve problems. Lots of programs alleviate poverty, or homelessness, but we still have large populations of people who are poor and homeless. Large scale challenges, like climate change, will clearly require large scale solutions. That’s why MacArthur Foundation launched 100&Change competition last year, promising $100 million to fund a winning proposal that promises to make measure progress towards solving a significant problem.

Even large scale philanthropic support can only go so far. Foundations are legally obligated to give away at least 5% of their assets each year in grants, but the leaders of foundations are becoming increasingly aware that they might have more influence on the world with the other 95% of the money they control, via the investments they choose to make. For that reason, foundations are joining the ranks of so called impact investors who put their money into companies that deliver both financial returns and social/environmental improvements. In April, the Ford Foundation announced it would devote $1 billion of its investments to “impact” funds, prompting me to blog about the implications of foundation impact investing.

The amount of money foundations can invest to produce social good is dwarfed by the massed funds of individuals. In 2014, US foundations controlled $715 billion in assets. As of March, 2016, Americans held $6.8 trillion in all employer-based defined contribution retirement plans, $4.8 trillion of that in 401(k) plans, and that’s only one small piece of the investment fund landscape. The US is seeing rapid growth in the number of investors choosing, or pressuring their fund managers to choose, socially responsible investments. As of 2016, $7 trillion was invested in strategies focused on environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) causes in the US, compared to $639 billion in 1995 (source here). Impact investing is a subset of ESG that focuses on producing active good rather than merely avoiding harm. Last year investors put $22.1 billion towards 8,000 such impact investments, and there is about $144 billion total in the impact investing market.

If, or when, the number of benefit corporations reaches critical mass, they will be able to tap into these cause-based investor dollars as a group. I can see a future in which I could not only choose an investment portfolio that does general social good, but a fund that promises specific returns, such as educational impact, along with my financial dividends.

Why should museums care? Here are a few reasons that have occurred to me:

- The proliferation of benefit corporations—financially self-sustaining organizations documenting the good they do—Is yet one more trend that may lead the public to question why nonprofits deserve their charitable support.

- As successful benefit corporations create a growing body of for-profit business models around doing social and environment good, museums can use these examples as inspiration for developing their own mission-related earned income streams. At very least, it will help museum closely define which of their mission-based activities are immune to monetization (collections storage? academic research?) and hone their pitch on why those functions are worthy of philanthropic or government support.

- If the benefit corporate structure system and impact investing mature and intertwine as their proponents hope, they will create a massive source of capital for mission-based organizations. In that scenario, it might be attractive for a museum to become a benefit corporation, satisfying shareholders rather than members, in order to tap these funds; or to create sister organizations with benefit corporation status in order to have the best of both worlds.For those of you who held out to the end of this essay—I’d love to see your comments below. Next up, a briefing on B corps, a voluntary certification program that for profit and nonprofit companies can use to demonstrate their social and environmental accountability.

Posted on behalf of Angie Kim, President and CEO, Center for Cultural Innovation and CFM Council member, who offered two comments on this essay:

1) The benefit corporation is multi-bottom line but it's up to the company to determine what "good" to pursue. It can be social (employee well being) OR environmental (recycling all materials). Benefit corporations should not be assumed to be all three: people, planet, and profit. They can still be just two of the three (but always profit).

2) The framing of benefit corporations relative to nonprofit status is a bit funky since that's not the origin story. Folks in the nonprofit sector should know these are cropping up as potential partners, community members, etc., but not as an alternative to the nonprofit corporation model. The Benefit corporation was designed specifically to address a failure of proprietary corporations being only focused on profit. Until B Corps were recognized at the state level, it was a legally fire-able offense to be an executive NOT maximizing profit. Consider American Airlines shares dropping recently when the CEO tried to prioritize employee well being by proposing to raise wages. Hence, S Corps reflected a problem of capitalism (not the third sector) as manifested by the American corporation.