This article originally appeared in the July/August 2017 issue of Museum magazine.

The lasting legacy—and future implications— of AAM’s landmark 1992 publication.

Diversity. Equity. Accessibility. Inclusion. These terms (together, “DEAI”) are central to current, often animated discourse across the field, reflecting a significant time of transition for museums. With the important conversations now taking place, colleagues who were around in the late 1980s and early 1990s may be experiencing a sense of déjà vu. Then, as now, thought leaders grappled with the past, present, and future of museum practice as they examined museums’ evolving role in a pluralistic society.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums. This 1992 AAM report, edited by Ellen Hirzy, was the result of nearly three years of work by the AAM Task Force on Museum Education. Chaired by Bonnie Pitman, this group was made up of colleagues from across the field brought together to identify critical issues in museum education. Excellence and Equity includes 10 principles and recommendations— from assuring the commitment to serving the public is at the core of everything the museum does, to enriching our understanding of our collections and the diverse cultures they represent.

To recognize the silver anniversary of Excellence and Equity, AAM reached out to several thought leaders who were part of that original task force, as well as to colleagues now working in education and DEAI. We asked them to share reflections on the “then, now, and next” of Excellence and Equity. All interviewees—Gail Anderson, Keonna Hendrick, Elaine Heumann Gurian, Ellen Hirzy, Nicole Ivy, Michael Lesperance, Sage Morgan-Hubbard, Annie Leist, Bonnie Pitman, Cecile Shellman, Sonnet Takahisa, and Franklin Vagnone—provided rich commentary and insight, both practical and philosophical. Those who were on the task force agreed that the group’s diversity gave great strength and unity to the work at hand. At the same time, this diversity presented communication and ideological challenges. The sometimes contentious but always-collegial discussions that resulted both informed Excellence and Equity and ultimately led to significant change in the field.

The interviewees who were not on the task force acknowledged that Excellence and Equity provided a foundation on which current DEAI dialogue and action have been built. They also recognized that much work remains to be done. All agreed that the effort to address DEAI in the museum field is ongoing; there will never be, as Cecile Shellman pointed out, “an endpoint at which we can sit back and congratulate ourselves for finally being inclusive.”

THEN

What was happening in the museum field in the late 1980s/early 1990s that saw the formation of the AAM Task Force on Museum Education, resulting in Excellence and Equity?

Ellen Hirzy (EH): By the time AAM published Museums for a New Century in 1984, education was a vibrant force in most museums thanks to more than 20 years of activism and advocacy. But as we observed in that report, there was still a “tension of values” between collections and education. Museums needed to move beyond traditional program-centered notions of education, the report said, toward something deeper. Those were fairly radical statements at the time. Museums for a New Century [also] pointed to other issues: low salaries; race- and gender-based inequity in staff hiring, advancement, and leadership; mostly white museum boards; and the urgency of embracing the transformational demographic change that was happening. In this context, the AAM Task Force on Museum Education was formed.

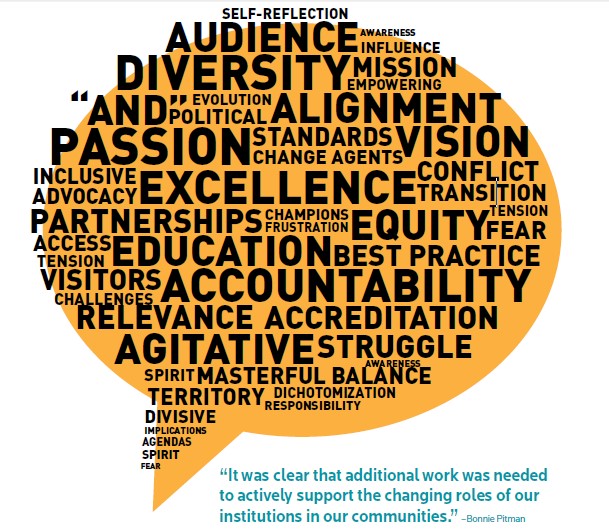

Bonnie Pitman (BP): The late ‘80s and early ‘90s was a tumultuous time. The Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) and the Museum Assessment Program (MAP) were emerging, Accreditation needed a rethinking, and standards for the field—especially in ethics— were in the crosscurrents. It was clear that additional work was needed to actively support the changing roles of our institutions in our communities. I was appointed chair of the task force, and the group was charged with writing the document and reaching consensus in the field for its support.

Gail Anderson (GA): There was a need to declare and finally acknowledge that education was the central role of museums,

not a sidelined department, and that if our museums were to be successful they needed to be inclusive.

Sonnet Takahisa (ST): I was relatively new to the field at the time of the task force, but my view of the field was skewed because I lucked out with some amazing mentors. At the Boston Children’s Museum, the Seattle Art Museum and the Brooklyn Museum, I saw my role as an activist or community organizer, raising awareness of the fact that museums hold their collections in public trust, encouraging a broader range of people to take an interest and pay attention to what belongs to them and to participate in the meaning-making process. I thought all museums were like that; I did not realize that the people who had hired me and encouraged me were at the vanguard of a movement!

Describe the task force’s complex work.

EH: It was an intense process, but a highly collaborative one. Traditionalists who were protective of a museum hierarchy with collections at the pinnacle were still reluctant to share authority with education practitioners and advocates. Looking back, it was no small feat to arrive at these two sentences: “By giving [Excellence and Equity] equal value, this report invites museums to take pride in their tradition as stewards of excellence and to embrace the cultural diversity of our nation as they foster their tremendous educational potential.”

BP: The diversity of the task force of 25 colleagues was both a gift and one of the great challenges of the writing of the report. We went through 42 drafts; at that time they were sent back and forth on fax machines of rolling paper, and we used the mail system! Each person on the task force had points of view that were important— the issue was how to craft these divergent ideas into a document the whole profession could support. One vision we all shared was that together, excellence in education and collections made stronger and more inclusive institutions.

Elaine Heumann Gurian (EHG): In 1992, an article that I wrote reflecting on the experience of being in the task force was published. The article was entitled “The Importance of ‘And.’” The idea I learned in that group about the issues of complexity, ambivalence, and multiplicity…has become the leitmotif of all my subsequent writings: more than one idea can be held simultaneously, and the word “primary” can be used for more than one idea at a time.

How did Excellence and Equity affect museum education, educators, and the field?

BP: The change was profound. I spent much of the next two years of my life at meetings with museum professionals, other professional organizations, foundations, and government agencies advocating this perspective. You saw dramatic changes in the MAP and Accreditation reviews because of this work. Foundations such as the Pew Charitable Trust and MetLife stepped forward with funds to support new initiatives in museums that embraced their work.

ST: For museum educators, Excellence and Equity was a great manifesto that paved the way for new program experiments and formats. At the Brooklyn Museum, it provided fuel to bring in outside evaluators to help us conduct research about the impact of our educational programs on the participants. We used the language of Excellence and Equity to articulate for students, their families, and administrators, the unique attributes of museums.

GA: Education evolved into the visitor-centered museum in the ensuing years. Many institutions shifted the nature of exhibitions, programs, and the public engagement they offered. Conversely, I think diversifying boards, staff, and volunteers made little progress in the ‘90s (and even now).

EHG: Even though we were unaware of the long-lasting effect Excellence and Equity would have when it was written, we hoped to make a difference in the field. We were sincere in our work and respectful of each other even when enmeshed in passionate disagreement. In retrospect, the activity of creating Excellence and Equity was a model of political best practice. We all were trying to come to an agreed new cooperative space without losing our deeply held positions. I wish for that process to be used more widely now. Clearly, the issue of winners and losers is more paramount than ever considering today’s American politics.

NOW

How does today’s museum landscape compare to the field when Excellence and Equity was published?

BP: There are similarities between the ‘90s and the challenges we are facing now. The issues of changing audiences, finding new ways to connect and engage with them both in the museum and digitally, the shifting demographics of our communities, and other societal issues are all the same…[But] donor giving is changing, and with the potential [threats to funding] of IMLS, National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), and National Endowment for the Humanities(NEH), strain is being placed on the entire community.

GA: In this political climate, issues of immigration, identity, equity, and racism are bubbling up in every conversation among every citizen and in our museums. This is a call for museums to be bold in their work as they strive to really make a difference in the lives of people in their communities and beyond.

Michael Lesperance (ML): When Equity and Excellence came out, there were precious few LGBTQ-related exhibits, programs, or operational guidelines. Museums have become, as a whole, much more welcoming to broader segments of their communities. In many cases this has been the result of conscious decisions, but too often external forces—I’m thinking mostly of transformative social media—have been the real driver. The commitment to equity needs to come from inside, not be shaped by the external environment.

Franklin Vagnone (FV): I would say that communication is the primary shift that has occurred. We have changing expectations, speed, and need for detail in all of our communications. Things are moving far too quickly for traditional cultural organizations that do not seem nimble or capable.

ST: We know more about our audiences and potential audiences now, in part because we are inviting conversation and asking for input and actually listening. Educators work collaboratively with marketing and visitor services, using more sophisticated tools to analyze participation and impact, allowing us to be more effective in working with curators around exhibition, program design, and outreach.

How far have we come in addressing the key ideas of excellence and equity?

EH: I think museums have made the most progress in the principles we called mission, learning, scholarship, interpretation, collaboration, decision-making, and leadership. But [in] the three principles that are related to equity… we haven’t come far enough.

Cecile Shellman (CS): Twenty-five years ago, this landmark report reverberated throughout the field and permeated practitioners with simple truths: that we needed to embrace public service as a core tenet of our mission; that we needed to be more inclusive; and that community relationships were key. In 2017, we still grapple with the same challenges. Rather than viewing this as an indictment of our inability to “get things right,” our continued work requires an investment from each of us and the knowledge that this is the work of social justice, not merely community engagement.

FV: I still see major issues with inclusion in both the boards as well as staff. Museums are attempting to—and aspire to be—agents of social connection. I think, however, that many consider this to be a programmatic element and not a fundamental leadership and decision making dimension.

ML: The recently launched AAM “LGBTQ Welcoming Guidelines” (see page 36) provide a road-map for including

LGBTQ concerns in every part of a museum’s internal and external operations. More museums are curating exhibits, developing educational programs, and implementing staff policies based on a commitment to equity. I wonder if the authors of Excellence and Equity could have imagined how openly LGBTQ content, staff, and programming would be shaping many museums in 2017.

ST: We no longer have to justify audience research and evaluation. As funders demand greater accountability about the impact of museum programs for audiences, we are embedding assessments that reveal strengths and areas that need improvement.

Annie Leist (AL): For people with disabilities, the barriers to participation may be as much practical as they are conceptual. Removing these barriers (through solutions such as ASL interpretation, verbal description of objects, captioning of programs and media, and more accessible digital content) costs money. Too often these solutions are considered to be augmentations or add-ons useful only to a small percentage of visitors, which makes resource allocation even more challenging.

Keonna Hendrick (KH): Public discussions on gender, sexuality, and ability are becoming less binary and more nuanced. Artists, historians, activists, and scientists are both leading and responding to these shifting discourses around identity while critiquing the oppressive histories that have marginalized many groups of people.

What are examples of museum successes and challenges in addressing their public dimension with regard to excellence and equity?

CS: After 9/11, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum (where I was then employed) realized that [it needed to respond] thoughtfully to the horrific attack and the ensuing anti-Muslim sentiment in Boston. Robust dialogues on diversity were held at the museum among high school classes. The program eventually won a national award for its impact, but more importantly, museum work at that institution continued to be defined as the work of changing lives. At the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, a challenge is engaging staff who hold a multiplicity of beliefs across spectra and among four different museums.

ST: Programs such as the Explorers program at the Newark Museum exemplify a commitment to changing the face of our institution. Part college and career preparation, part youth leadership and a part-time job, the program gives 35 predominantly “minority” high school students invaluable exposure, access, and experiences.

GA: The Oakland Museum of California has adopted a bold approach to how they envision, develop, and engage their audiences through exhibits, including a recent show on the Black Panthers and another on marijuana. This has

been supported by an entirely new organizational structure that broke old barriers and siloed departments.

ML: The AAM LGBTQ Alliance recently spoke out against the Trump administration’s withdrawal of Title IX Guidance allowing transgender students to use restroom facilities of their gender. Museums must make true equity part of their core; otherwise, any gains my community and other traditionally marginalized groups have made will be threatened.

NEXT

In what ways might Excellence and Equity be relevant as we head into the future?

Sage Morgan-Hubbard (SMH): Excellence and Equity is 25 years old, but the key ideas and principles are still relevant for our times. In an expanded version of the report, I would like to see each of the recommendations accompanied by case studies that can provide clear examples for museums to follow. We should be able to make more museums following these principles mandatory for recruiting and hiring in museums, educational programs, accreditation, and grant support.

EH: The museum field still needs Excellence and Equity as a reminder of the work that remains. The work is systemic and internal, and it must be done with greater reflection, tenacity, and authenticity. It’s not just about how museums look from the outside. It’s about how museums as organizations behave on the inside as they decide just what values drive their work and then put those values into action.

ST: Excellence and Equity reminds us that we need to constantly review, challenge, and reassess the assumptions and biases that inform our choices, as we continue to create opportunities for conversation, contemplation, and reflection.

EHG: We cannot proclaim [Excellence and Equity] a success without acknowledging that implementation actions—even difficult budgetary ones—should follow. In public service, both excellence and equity can occur in each of our museums if we so wish it, and public service itself can become one of the primary missions of each of our museums if that becomes our collective intention.

KH: Excellence and Equity offers recommendations for developing more diverse and inclusive museums. We need to revisit those recommendations and consider where we succeed and where we fall short in our individual and institutional practices. Once we do this, we need to be honest about what communities we have to be intentional about engaging.

Where do you think the field is headed with regard to education, diversity, inclusion, equity, and accessibility?

Nicole Ivy (NI): Today, visitors have access to more information than ever before right at their fingertips, bringing knowledge from powerful search engines into the museum via smartphones and other handheld devices. Advances in augmented reality mean that visitors can layer other images on top of the objects on view in museums. The changing educational landscape requires that we continue to acknowledge the multiple layers of meaning that visitors provide even as we adapt new ways to create immersive and compelling learning experiences in our museums.

AL: Museum collections and museum staffs may [not yet] be as diverse as the general populations of the communities in which they exist. However, in the field of accessibility, I have witnessed a dramatic increase in the number of conversations and movements on local and national levels to recognize the role of not only audiences with disabilities, but also artistic creators and cultural service providers with disabilities.

KH: It’s challenging to identify exactly where we’re headed in terms of inclusion, cultural equity, and accessibility because not everyone shares the same goals, understanding, and language around these issues. There are many individuals working to push their institutions and individual practice beyond diversity toward anti-racist actions that begin to dismantle racism within the institutional culture. We still need to see more of this across the field.

NI: I think we will see more collaboration between museum educators, curators, and public engagement staff to create truly magnetic and integrated experiences. I also expect to see more emphasis on universal design in our physical spaces and user experience in our digital spaces

A PDF of the 2008 reprint of Excellence and Equity and an expanded version of this article are available online in Alliance Labs: http://labs.aam-us.org/blog/category/strategic-plan/diversity-equity-accessibility-inclusion/.

Greg Stevens is the director for professional development at AAM. Gail Anderson is president, Gail Anderson and Associates. Keonna Hendrick is a cultural strategist and educator. Elaine Heumann Gurian is principal, Elaine Heumann Gurian, LLC. Ellen Hirzy is an editor and writer. Nicole Ivy is a museum futurist and director of inclusion at AAM. Michael Lesperance is principal, The Design Minds, Inc., and chair of the AAM LGBTQ Alliance. Sage Morgan-Hubbard is the Ford W. Bell Fellow for P–12 Education at AAM. Annie Leist is special projects lead, Art Beyond Sight. Bonnie Pitman is distinguished scholar in residence, Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History, and co-director, Center for Interdisciplinary Study of Museums, University of Texas at Dallas. Cecile Shellman is diversity catalyst, Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. Sonnet Takahisa is deputy director for engagement and innovation, Newark Museum. Franklin Vagnone is principal, Twisted Preservation Cultural Consulting.