The Smithsonian Folklife Festival won AAM’s PIC-Green Professional Network 2017 Sustainability Excellence Award for Programming. Here, James Deutsch, Program Curator for the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, and Eric Hollinger an archaeologist from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History explain why and how they changed the way waste is diverted for the festival.

For many years, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival—established in 1967 as a living, outdoor “museum without walls” to highlight traditional cultures around the world—struggled with how to responsibly handle the tremendous amount of waste generated by as many as a million Festival visitors to the National Mall. Vendors for the Festival had typically provided Styrofoam and other plastic disposable containers, plates, bowls, cups, and cutlery, which overflowed the trash cans distributed by the National Park Service and the Smithsonian. In spite of efforts by Festival staff to keep up, trash from overflowing bins blew around the Mall—making for an unsightly and somewhat disturbing scene among the museums and monuments. Mountains of trash bags, pulled from the bins, were piled along the public pathways of the Mall for the NPS to remove late each day. Even bottles and cans, normally considered easy to recycle, were left to the trash. The Festival faced increasing criticism from the public and staff to do something about the very visible and embarrassing example of unsustainable waste practices. The pressure was on to practice the sustainability increasingly being preached by the Smithsonian Institution; the largest museum complex in the world and one of the most venerated museum institutions in the Nation. By 2007, the Folklife Festival, Smithsonian Facilities and concerned staff and volunteers began to work to try to “green the Festival.” The ambitious task was great and the obstacles to attaining a sustainable Festival were tremendous. The most basic goal was to convert the waste stream from non-compostable, non-recyclable disposables like Styrofoam, collect it in an orderly fashion and get it to facilities that can convert it to useful resources. It sounded simple enough, but the logistical, financial and cultural obstacles to be overcome were daunting. How do you convince many different food vendors, often different each year, to change over to more expensive compostable disposables when they are struggling just to feed the throngs of guests? What do you do if they run out of compostable cutlery and want to switch to plastic to keep the crowds fed? How do you get the culturally and linguistically diverse public to keep their recycling, compostables and “landfill” trash separate when you have 300 trash bins spread across a huge area? How can you sustain operations daily over a two-week period, including July 4, no matter the weather conditions? And how can it be done year after year when the vendors, programs, locations, and layouts of the Festival change every year according to Festival themes?

The ambitious task was great and the obstacles to attaining a sustainable Festival were tremendous. The most basic goal was to convert the waste stream from non-compostable, non-recyclable disposables like Styrofoam, collect it in an orderly fashion and get it to facilities that can convert it to useful resources. It sounded simple enough, but the logistical, financial and cultural obstacles to be overcome were daunting. How do you convince many different food vendors, often different each year, to change over to more expensive compostable disposables when they are struggling just to feed the throngs of guests? What do you do if they run out of compostable cutlery and want to switch to plastic to keep the crowds fed? How do you get the culturally and linguistically diverse public to keep their recycling, compostables and “landfill” trash separate when you have 300 trash bins spread across a huge area? How can you sustain operations daily over a two-week period, including July 4, no matter the weather conditions? And how can it be done year after year when the vendors, programs, locations, and layouts of the Festival change every year according to Festival themes?

Many Festival veterans and administrators felt it just could not be done; too many variables would need to be controlled. Even if it could be done, the costs in labor, materials, and equipment would add too much to a budget that was always challenging given the key expenses including featuring Festival presenters from all over the world. Old habits were already well-ingrained. Methods for feeding the crowds and getting the waste off the Mall, though not always pretty or sustainable, did the job, so proposed changes to established practice were met with apprehension.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleWe began with recycling. Beginning in 2007, Eric Hollinger an archaeologist from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and Ivan Graff, the head of the Smithsonian Facilities Recycling Task Force worked with Robert Schneider, Technical Director of the Folklife Festival, and his staff to study the movement of Festival crowds, the position of bins, the behavior of bin users, and the composition of the waste, as well as practices in the vendor kitchens. Smithsonian Facilities purchased 75 Clearstream recycling frames and arranged for the Natural History Museum to add a dumpster for the recycling on the Mall in front of the museum. A few volunteers roved the Festival to pull trash out of the recycling and recycling out of the trash. That first year the Festival recycled 1.75 tons of bottles and cans that would otherwise have been lost to landfills; humble beginnings, but a huge step in the right direction. Over the next few years, more Clearstream frames were purchased and trash bins were reduced until there was recycling next to each trash bin. At the same time, the Festival and volunteers worked with the food vendors to move large quantities of bottles and cans and cardboard from the back of the kitchens to the nearby museums for recycling with the building operations.

While visitors appreciated the addition of recycling, they challenged the Festival to find ways of eliminating the Styrofoam and other waste, still very noticeable. The Festival began asking food vendors to voluntarily use compostable disposable products in an effort to get away from Styrofoam. Some tried, but as often happens, they underestimated the size of the crowds and quickly ran out. The vendors also complained that it was difficult to find the right compostable version of a container and that the compostable products were too expensive. By 2012, the Festival attempted to contractually require the vendors to use only “biodegradable or recyclable” disposables. The language proved insufficient and only about half of the products provided by the four vendors could be diverted. It turns out that biodegradable is not the same thing as compostable. Some of the vendors pointed to the #6-resin code enclosed by the arrows in a triangle “recycling” symbol on the back of their Styrofoam containers and argued that they had met the contract requirements because the symbol proved they were recyclable. The vendors, along with most Americans, did not know that #6 polystyrene is almost never recycled and the resin code identified only the type of plastic, not its potential for recycling. So we realized the contract language needed to be very specific in providing definitions of compostable and recyclable products and we needed to provide assistance by providing examples of what common materials do and do not meet the criteria. We also found that compostable product suppliers would run through their stock quickly given the sudden surge of hundreds of thousands needed over just a few days. Suppliers needed advance notice to concentrate enough product near DC to be ready to meet the demand.

As we attempted to convert to the proper materials, we also wrestled with how to collect and remove the compostables. A wide range of ideas were considered; could we take the trash bags to a side compound to be sorted by volunteers? Moving the bags and the space needed for a large compound proved problematic and we realized the public would have no idea, nor trust, that we were actually composting the waste. Could compactor trucks roll continuously around the paths of the Mall while crews walked behind them sorting the bags brought to them? The cost of the trucks, fuel, and crews was too much and trucks rolling right through the dense crowds all day posed many challenges. Could we just put complete sets of “compostable,” “recyclable,” and “landfill” bins all over the Mall and let the visitors separate them at the source? Our diverse public, even those who felt confident in their recycling knowledge, could not easily distinguish the compostable plastic cutlery, cups and clamshells from non-compostable plastics and recyclable plastics so they would unwittingly mix and contaminate too much.

The visitors, coming from all over the world, needed guidance. So we provided volunteers trained in recognizing the various products being used by the Festival vendors and common non-Festival waste brought in by the public. Because we did not have enough volunteers to stand by 200 to 300 stations scattered around the Festival, we removed most of the bins and concentrated them in clusters beside seating areas and high-traffic entry and exit points. We first had to prove this collection method would work by conducting a pilot project during the 2012 Smithsonian Staff Picnic, held for more than 6,000 employees on the Festival grounds during a two-day break in the middle of the two-week Festival. We hid most of the trash bins from the Festival grounds and concentrated a few landfill, compostable, and recycling receptacles at five “stations” next to seating areas. Product specimens being used by the food vendors were glued to display boards as identification aids and briefed volunteer staff guided “customers” to the proper bin for disposing of their own materials. Even with only half of the vendor products correctly meeting requirements, in just a few hours we collected more than 600 pounds of compostable organics. We demonstrated that only a handful of stations with 10 volunteers could assist thousands of visitors in disposing of their own materials and no additional sorting would be necessary. We also showed that the role of these “resource recovery station” attendants was most important as educators; explaining details like which items were made of compostable corn-based plastics and how they could be identified by the resin codes and why it was unacceptable to commingle compostable plastic cups with plastic bottles (even though the cup is a round peg and the recycling has a round hole in the lid!). Our stations became exhibits, clarifying that there is actually no “away” when one throws away trash. It all goes somewhere and has to be handled by someone and can be wasted or reused depending on where it goes or how it’s handled. That’s why these are “resource recovery stations” rather than “trash” stations; the term helps us recognize that the materials are resources with value we just need to be cognizant of how they are recovered and diverted for reuse.

The visitors, coming from all over the world, needed guidance. So we provided volunteers trained in recognizing the various products being used by the Festival vendors and common non-Festival waste brought in by the public. Because we did not have enough volunteers to stand by 200 to 300 stations scattered around the Festival, we removed most of the bins and concentrated them in clusters beside seating areas and high-traffic entry and exit points. We first had to prove this collection method would work by conducting a pilot project during the 2012 Smithsonian Staff Picnic, held for more than 6,000 employees on the Festival grounds during a two-day break in the middle of the two-week Festival. We hid most of the trash bins from the Festival grounds and concentrated a few landfill, compostable, and recycling receptacles at five “stations” next to seating areas. Product specimens being used by the food vendors were glued to display boards as identification aids and briefed volunteer staff guided “customers” to the proper bin for disposing of their own materials. Even with only half of the vendor products correctly meeting requirements, in just a few hours we collected more than 600 pounds of compostable organics. We demonstrated that only a handful of stations with 10 volunteers could assist thousands of visitors in disposing of their own materials and no additional sorting would be necessary. We also showed that the role of these “resource recovery station” attendants was most important as educators; explaining details like which items were made of compostable corn-based plastics and how they could be identified by the resin codes and why it was unacceptable to commingle compostable plastic cups with plastic bottles (even though the cup is a round peg and the recycling has a round hole in the lid!). Our stations became exhibits, clarifying that there is actually no “away” when one throws away trash. It all goes somewhere and has to be handled by someone and can be wasted or reused depending on where it goes or how it’s handled. That’s why these are “resource recovery stations” rather than “trash” stations; the term helps us recognize that the materials are resources with value we just need to be cognizant of how they are recovered and diverted for reuse.

With the proof of concept for the collection approach, we now needed a way to get the bags of organics off the Mall and to an industrial composting facility where it could be processed into the “black gold” landscapers and farmers love. This is where a little more applied anthropology came in handy. Rather than buying special trucks or adding more dumpsters to the Mall to collect the bags of organics, we just observed how the bags, when considered trash, were already being removed from the Mall. As previously noted, they were being piled high beside park benches next to the paths of the Mall; once a day an NPS compactor truck rolled along and workers tossed the bags in and off they went to the next pile and ultimately to the landfill. For managers to find change acceptable, and in the interest of efficiency, it is often best to change operations as little as necessary. So with the resource recovery stations in place, we opted to pull the bags of organics and set them next to the stations. Three times per day, a compost hauling company sent a compactor truck onto the Mall to roll along while we counted and tossed the bags into the back. This removed the piles promptly, and the truck, clearly signed as a “Food Waste Recycling” truck, was sometimes met with cheers and applause from visitors as they could see the mountains heading to composting. The few landfill bags produced by each station were still set by the park benches for the NPS to remove but they were much less visible. These were the methods applied in 2013 when the Folklife Festival fully adopted the program of diverting everything possible from the public and the restaurant back of house operations.

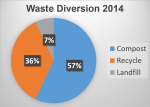

In 2013, the stations, staffed by volunteers and now tented for shade, were equipped with chairs, a table and a tub containing gloves, spare bags, a sample bag of finished compost and a binder with information and images showing how each material type is processed after it leaves the Mall. The stations were set near approaches to seating areas and in spots where they were very visible and fairly convenient to access. Signs were hung from the tents to mark them as Recycling and Compost locations from a distance and signs were hung on the bins sorted by material. Each station had from one to three sides lined with receptacles with a ratio of about one landfill bin for every two compost bins and two recycling receptacles. Because the vendors did a better job in 2013 or providing the proper types of disposables, so little landfill materials were brought to the stations that they produced only about one bag of landfill for every 10 bags of compost. Some busy stations, during a dinner rush, generated as many as 32 bags in only a few hours. The bags, weighing about 25 pounds each, were counted and recorded as they were removed. The restaurants were also asked to compost their organic waste as it was generated at the back of the kitchens. At the end of the 2013 Festival, a total of 74 percent of all the waste generated by the Festival had been diverted for recycling or composting.

To our knowledge, this was the largest sustained composting effort to ever take place on the National Mall. The response from staff and the public was very positive. We had demonstrated that it was possible after all. The Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage recognized the value of the waste diversion program for the Festival and decided to include sustainability along with all of its Festival operations. Smithsonian Facilities recognized the achievement of the Festival and offered to fund a pair of sustainability interns to help with the program in 2014. This allowed for more time for the restaurants, the heavy weight generators, to be monitored to make sure their waste was placed in the proper bins behind the kitchens for pickup. The vendors also received more extensive training, both in advance of the Festival and also while in operation. This resulted in diversion rates that seem astoundingly high: 93 percent in 2014 and 2015, and 96 percent in 2016, and 91.3 2017. We have continued with this basic approach for the waste diversion program while continuing to experiment with signage, station positioning and configurations, and procedural refinement. We have relied on extraordinarily dedicated coordinators for our sustainability efforts—Sarah Gaines in 2014 and 2015; Emily Claire Mackey in 2016 and 2017— to oversee the operations. Each year presents its own new challenges as we usually have to start over with new restaurant vendors, many new volunteers added to our growing core team, new interns, and new site layouts. But the Smithsonian remains committed to promoting sustainability and setting an example for other museums and outdoor events to follow.

To our knowledge, this was the largest sustained composting effort to ever take place on the National Mall. The response from staff and the public was very positive. We had demonstrated that it was possible after all. The Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage recognized the value of the waste diversion program for the Festival and decided to include sustainability along with all of its Festival operations. Smithsonian Facilities recognized the achievement of the Festival and offered to fund a pair of sustainability interns to help with the program in 2014. This allowed for more time for the restaurants, the heavy weight generators, to be monitored to make sure their waste was placed in the proper bins behind the kitchens for pickup. The vendors also received more extensive training, both in advance of the Festival and also while in operation. This resulted in diversion rates that seem astoundingly high: 93 percent in 2014 and 2015, and 96 percent in 2016, and 91.3 2017. We have continued with this basic approach for the waste diversion program while continuing to experiment with signage, station positioning and configurations, and procedural refinement. We have relied on extraordinarily dedicated coordinators for our sustainability efforts—Sarah Gaines in 2014 and 2015; Emily Claire Mackey in 2016 and 2017— to oversee the operations. Each year presents its own new challenges as we usually have to start over with new restaurant vendors, many new volunteers added to our growing core team, new interns, and new site layouts. But the Smithsonian remains committed to promoting sustainability and setting an example for other museums and outdoor events to follow.

Wonderful Eric! I applaud your dedication.