Wherever you are on the journey to digitize museum collections, there are questions to address regarding who will use these millions of digital assets, and how. Teachers and their students seem to be obvious audiences, but what does it really take to be accessible, relevant, and useful to them? The Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access aimed to find out in a two-year study that included classroom observations, surveys, analyses of collection metadata, and investigation of the uses teachers make of digital resources. These findings can aid museum educators, in particular, as well as anyone interested in digital learning using the resources museums are increasingly making available.

The Smithsonian Learning Lab, an online platform for discovering resources and creating learning experiences, launched in 2016, based on years of research with educators. Once the Lab was up and running, the museum team and independent researchers at the University of California, Irvine, wanted to see if the intention to make digitized museum resources accessible for deeper learning was working with the intended audience. More specifically, we wanted to find out:

- How and why teachers make learning activities with museum digital assets and what promotes their success.

- Supports that teachers need for the meaningful use of a platform and digital assets, given their varying access to and expertise with technology and curriculum development, and their experience using museum resources.

First, let’s review a major anticipated problem that turned out not to be an issue:

Technology isn’t a significant barrier.

In short, teachers figure it out, whether they have one-to-one computing, share computers, or have no computers at all! Enterprising teachers, when faced with a new web platform, downloaded resource images and projected them on a whiteboard, organized small groups to work on the few computers they had, or even downloaded and printed digital images to use during classroom discussions. They not only adapted based on their situation and experience, they also showed remarkable creativity.

On the other hand,

Brief, effective training makes a difference.

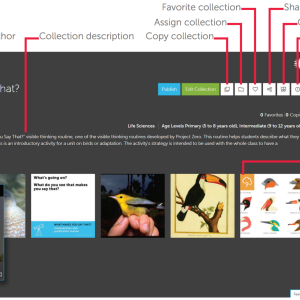

Participation in training—even a one-hour orientation at a conference—improves use. This may be as simple as a walkthrough of features (in the case of our platform) or showing samples of work produced by other educators.

That’s the good news. On the downside, because most teachers have little or no training in or orientation to what museums collect, study, and make available, they are likely to use museum resources in one-dimensional ways. An example of this might be using a photo of a Civil War battlefield as a simple illustration (like a photo in a magazine article) rather than as a source of information or illumination, or a springboard to deeper learning.

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleBut everyone has to start somewhere. Even neophytes in the world of teaching with museum resources produce useful materials in the Learning Lab. Everything that they (and any user) creates is called “a collection” in the Lab’s terminology. A Learning Lab collection is a purposeful aggregation of digital resources.

The collections teachers make have three different purposes: to address a topic or theme (topical collections); to function similarly to a lesson plan (teaching collections); and to provide students with individual and group work (student activities).

Topical collections outnumber the others and are the only ones discussed here. These aggregations range from a few images or videos on a topic (e.g., “pandas”), to others for which selection may require more thought or subject expertise (e.g., “causes of pandemics”). Compared to teaching collections and student activities, which involve using the Lab’s tools, these topical collections are the simplest to make. In terms of how teachers use what they create, three main ways have been documented by classroom observations.

How teachers use digital museum resources

- For inspiration: resources (usually images) to stimulate creative writing or artwork. For example, an educator made a collection of origin stories from different cultures for this purpose.

- To provide context: resources that provide background and information on an issue. Examples include a collection with many items relating in some way to women’s suffrage, and another illustrating the historical context of a novel.

- As the basis for projects or activities: resources selected by an educator for later student use. As examples, a teacher preselects images of the U.S. presidents that students will use in media presentations or assembles fifty paintings depicting life in the 1930s that students will work with in a study of the Great Depression.

What makes museum resources useful to teachers

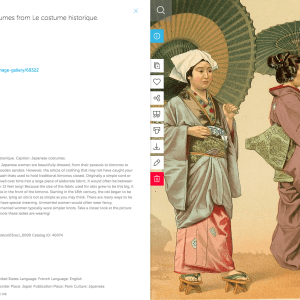

What characteristics of museum digital resources led to a teacher finding them in the Lab’s searchable database and using them to make collections? The answer is in the metadata! Our important finding is that the metadata categories that are important to the museum, such as dimensions and provenance, have much less relevance to a teacher than educational metadata: detailed description, historical and cultural contexts, and the significance of the resource.

To illustrate this point, let’s return to that Civil War battlefield image mentioned earlier. A teacher is going to want to know what to look for and how the image can help teach a topic. Are important or representative people depicted? What point of view is the image suggesting? Was the battle a turning point in the war or have some other importance? Did people of the time have reactions and responses to the image? Did the image influence political or other action?

If teachers cannot answer these questions themselves, they are unlikely to provide a resource to students without having those answers. For the museum to produce the necessary educational metadata, even if supported by statistically significant data showing its value, does present challenges because of time and expense.

Feasible solutions to those challenges might be found in selecting some items that have clear relevance to curricula and writing robust educational metadata only for them—the “study collection” in digital form. Another approach would be to write general historical and contextual information that can apply to several objects. To illustrate, an explanation of the tactics typically used in propagandistic posters could be included in the metadata of several different World War I military enlistment posters. The same explanation would also apply to another group of posters that, say, promoted public health measures during an epidemic, because the purpose of such works is similar across time and even different cultures. This general explanatory material need not detract from the importance of research on individual museum collection objects. Its purpose is rather to open their use to larger non-specialist audiences such as teachers and their students.

Isn’t context what traditional lesson plans provide? Yes, but published lesson plans lack the adaptability today’s teachers require in order to address their students’ diverse needs, curricular requirements, and time constraints. The research that led to building the Learning Lab showed that few educators used lesson plans as they were written.

Connecting digital assets to familiar pedagogical practices and teaching strategies can help bridge the gap between museum scholarship and classrooms.

Most teachers know and use time-honored techniques in their classroom. Identifying similarities and differences, graphically summarizing new learning, journaling, and peer-to-peer coaching are just a few of the most common. Museum educators often employ these techniques too, as well as those that develop competencies known as deeper learning. Deeper learning includes mastering academic content, knowing how to think critically and solve problems, and developing an academic mindset (when we show how to “think like a historian…or scientist…or curator” we are modeling those mindsets).

Museums can learn even more about these practices as they create digital learning materials and models by consulting with educators and aligning with national teaching standards and approaches such as Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero Thinking Routines.

Our research found that most teachers are adapters and implementers of instructional materials rather than creators. Even if they have the inclination, few have the time. So, in the Learning Lab, authoritative model collections are published by thirty Smithsonian museums and research centers. The Lab’s content contributors also include Smithsonian Affiliates such as the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh and collaborators outside the museum community, such as Michael Graves Architecture & Design. We will always want and need to offer such models that are based on our content knowledge and expertise, at the same time as we are looking for all possible ways to empower our audiences to use our resources for their own purposes (within our Terms of Use, of course).

Those educators who do have the interest, skills, and time to devote to content creation are creating fresh new learning experiences in the Lab, and it is exhilarating to follow and support their progress and achievements. To date they have published about four thousand collections in Smithsonian Learning Lab (in addition to twenty thousand they have kept unpublished for their private use). Here are just a few. Could we have thought of these ways to use our own resources to accomplish their learning objectives?

- Contemporary & Historic Architecture, by Jean-Marie Galing

- Who Belongs in Massachusetts?, by Laura Lamarre Anderson

- Angles in Motion, by Rachel Slezak

- The Great Gatsby and Modernism, by Annette Spahr

This article summarizes findings from the research report, Curation of Digital Museum Content: Teachers Discover, Create, and Share in the Smithsonian Learning Lab, which was supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The full report can be downloaded from the Smithsonian Learning Lab research page.

Michelle Knovic Smith is an associate director at the Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access focusing on digital media, communications, and the Smithsonian Learning Lab, a web platform for personalized learning. She can be reached at smithmk@si.edu. @SmithsonianLab

Comments