This article originally appeared in the July/August 2018 edition of Museum magazine.

As the number of art museums in the world has steadily risen, so has the number of biennials, triennials, and art fairs. Some survive. Many are unsuccessful. This latter fact would prompt a cynic to say there are too many such events. A romantic, however, would say there are too few.

In 2017, ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, an art museum in Aarhus, Denmark, for which I am the director, launched its own triennial. Why? Because we felt that society, more than ever before, needs art and culture to remind us where we come from, where we are today, and where we are heading.

The ARoS Triennial is our contribution to the dialogue about what it means to be a human being among other human beings—what really matters? To define what it means to be a human, we looked at how man has thought about and depicted nature through the ages. After all, how we live with or against nature will decide and define the future—for everyone.

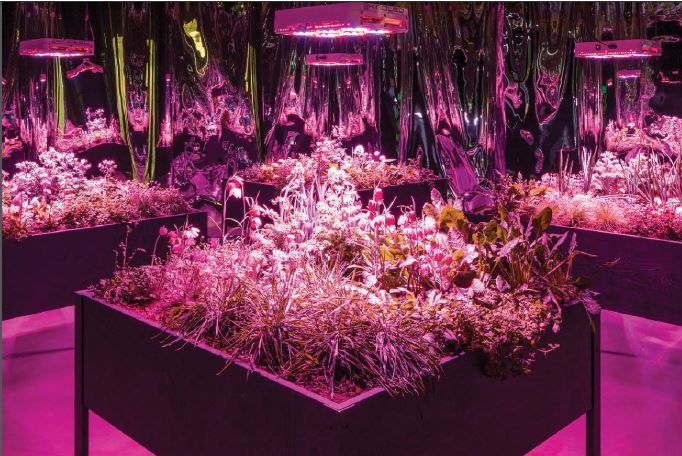

That’s why our first triennial exhibition was “The Garden—End of Times; Beginning of Times.” Throughout history, the garden has been viewed as a place of scientific study, an oasis for solitary reflection, or a place of entertainment. Our culture sees the garden as a meeting place of civilization and nature, a meditative space between two worlds. The garden meets various needs in different cultural contexts and becomes the perfect image of the diversity that makes up our world.

Historical Awareness, Contemporary Understanding

Biennials and triennials are usually linked to contemporary art, reflecting our own times. I would argue that a major problem facing today’s society and our ability to navigate in the world is a general lack of knowledge, not just about distant cultures but also about the various historical preconditions that form our present lives. For this reason, the time perspective of the Triennial was crucial, not just to recount an interesting story, but also to raise historical awareness.

The Triennial was split into three sections: “The Past” examined the landscape and man’s relation to nature viewed through the lens of art and the history of ideas. “The Present” looked at nature in the context of the modern city. And “The Future” examined artistic responses to ecological change. The exhibition occupied galleries in the museum (“The Past”), spread into urban spaces in the city of Aarhus (“The Present”), and continued along the coastal stretch south of the city (“The Future”).

“The Garden” chronicled man’s coexistence with and view on nature, how diverse worldviews (be they religious, political, ideological, cultural, or scientific) have manifested themselves in manmade natural landscapes for centuries. The narrative spanned 400 years, within which the audience could see works from Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain along with Robert Smithson, Doug Aitken, and Katharina Grosse.

The exhibition attempted to shed light on the ways in which man, over time, has transformed nature. What were the underlying ideals for this transformation, and what can these ideals tell us about man’s philosophy? We didn’t claim to be exhaustive; indeed, we would have been kidding ourselves if we pretended we could deliver the full story. We focused on selected historical cross-sections, giving visitors the opportunity to dip into various elements. This approach required visitors to actively participate in the conceptual and creative processes.

The Past, Present, and Future

The exhibition at the museum—“The Past”—set the historical framework for the Triennial’s overall focus, the transformation of the relationship between nature and man over time. We looked at how different historical periods altered the mutual influence of nature and man, often manifested in art.

The exhibition began with the Baroque landscape architecture of the mid-1600s, where nature was tamed, organized according to a Cartesian mathematical design, laid out in straight lines. The Baroque period was overtaken by the Rococo, with its lyrical gardens, then by the Enlightenment and the English garden, and finally by Romanticism and

a sublime view of nature.

The exhibition then depicted modernism and the modern times. The breakthrough of modernism in the early 20th century brought with it a new diverse approach to nature, spanning the Fauvist celebration of the human animal and the untamed forces—and the assertion by futurism that technology and machines have triumphed over nature—to

the surrealist ideas that the natural world is in a one-to-one relationship with man’s natural instincts and subconscious. In the exhibition, the inner landscape of the surrealists was followed by the massive land art projects.

Land art from the 1960s and 1970s seeks to establish a new relationship between viewers and works via a series of monumental and surprising encounters in the natural world. Many land art works intervene in nature, their monumentality stressing the fact that man will intrude on nature as he pleases. At the same time, the works show nature’s countermeasures: many of the works are perishable. The works cut into the natural landscape but will eventually erode according to nature’s dictates.

We then used the contemporary to put the presented history into context. Contemporary art will naturally react to society’s current challenges. One of the most pressing challenges today is man’s relationship with nature, given the realities of climate change and other detrimental environmental issues. Art provides a space for reflection where, for once, it is possible to merge often hard-held positions with separate sciences.

In the exhibition section titled “The Present,” which was outside in the city, we attempted to capture the manic now, which is defined by massive demographic changes, diaspora, immigration, global capital flows, and global cultural circulation. We focused on the accelerating global situation, which currently takes world images that have shaped our identity and turns them upside down. The idea of a homogeneous and stable world picture is replaced by a kaleidoscopic diversity of views and directions. The barrage of impressions in our global reality cannot be captured by the West’s centralized gaze. The central element in “The Present” was the impossible task of capturing the contemporaneous in a fragmented reality where the illusory idea of containing the world in a collective narrative has foundered.

Where “The Present” took stock of the global reality of our lives at this precise moment in time, “The Future” sought to unfold the new challenges facing humanity on the threshold of what has been termed the Anthropocene epoch, which is defined by man’s impact on the earth. This epoch punctures our preconception of man’s special position in relation to nature and of nature as a passive romantic entity.

“The Future” showed that nature is neither beautiful nor benevolent, nor something we are required to save; on the contrary, we must take advantage of potential we have so far been unable to perceive because our previous preoccupation with nature has veiled and romanticized it. The longing for unblemished nature stands in the way of inevitable evolution. Katharina Grosse’s installation along the coastline, Asphalt Air and Hair, started a large public debate—that spanned residents, politicians, and royals—about environmental issues.

The Beginning

Time and again, I find myself describing ARoS as a mental fitness center, a place to train and develop one’s brain and one’s thinking. The Triennial further develops this mindset: it is a platform for mental workout—somewhere to sharpen the critical gaze, the imagination. It is a place to gain a historical perspective on our identity in the world.

Art easily touches our emotions. “Using” art in this way also makes it easier for us as an institution to communicate with a wider audience. We wanted to use this opportunity to challenge our audience to be more aware and knowledgeable about the questions touching sustainability. We did not want to preach morality but instead stress

the importance of knowledge and conversations. In addition to the works of art and the educational text, we also held many talks on the topic, presented by a variety of experts. These discussions weren’t about art but instead about our profound understanding of how we can live with nature.vKnowledge is power.

“The Garden” was meant as a challenge, a generous gesture and an invitation to everyone interested in art, to professionals, and to those partial to a surprise. But the first triennial was never intended to be a goal in itself. It is part of a bigger plan to create new possibilities for art and its impact on the development of societies.

How Did It Go?

We had three clear strategic objectives with the first ARoS Triennial. First, we wanted to increase international awareness of ARoS and what we stand for. Second, we wanted to produce a triennial of high artistic quality. Third, naturally, we wanted the exhibition to attract many visitors.

We achieved all three goals. From April through October 2017, 863,500 people visited the ARoS Triennial, which attracted international media coverage, including from CNN Style, the Guardian, the Sunday Times, Vogue, Frieze, Artnet, the Art Newspaper, and the German television channel ZDF. In total, ARoS and the ARoS Triennial received more than 1,160 international digital press postings. And the reviews were great.

Erlend G. Høyersten is the director of ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum in Denmark.