I am not entirely comfortable with the fact that I’m looked to as something of a “thought leader’ in the museum field. I think of my writing, here on the blog or in CFM reports such as TrendsWatch, as the literary equivalent of sharing ideas with a friend over coffee. That this digital coffee klatch reaches thousand is, in truth, a bit intimidating. But since the scope of my potential influence is so large, I feel obligated to speak up when I find that I’ve been wrong. In this case, I think I’ve repeated the error multiple times for almost a decade. An error of that magnitude seems to call for public confession.

Back in 2010 I spoke at the Virginia Association of Museums conference, presenting an overview of some of the trends featured in CFM’s inaugural report, Museums and Society 2034. I touched on climate change and the long-term impact of the 2008 economic crisis, but I spent the most time on the changing demographics of the US.

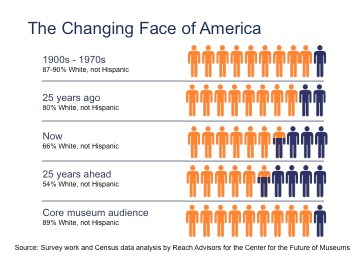

Citing the forecast by the US Census Bureau that the US will be “majority minority” sometime in the 2040s, with no one group (including Caucasians) forming a majority of the population, I highlighted the troubling observation that museum audiences do a pretty good job of reflecting American society…in the year 1900.The implication being that if we don’t change museum practice in order to be more relevant to communities of color, our audience will continue to shrink. The figure we used in the report to visualize this trend has been widely reproduced:

I felt pretty good about this part of the talk. I like solid, dependable facts. I like clear, compelling data visualization. And I saw this figure as representing a problem that museums can and should solve.

After the presentation, an older African American gentleman came up to me, clearly upset about my use of the phrase “majority minority future.” Shaking his head, he repeatedly said “You shouldn’t say that!” I made a classic error of communication, “If I say it again, clearly, maybe this person will understand.” I wish I had been a more skilled listener at the time. I never figured out why what I said had bothered him, and as a consequence, the conversation stuck in my memory.

A recent piece in the New York Times made me see that encounter in a new light.

In “Why the Announcement of a Looming White Minority Makes Demographers Nervous,” Sabrina Tavernise writes about a broad controversy swirling around projections of when America will reach the majority-minority tipping point. First, she cites recent research that shows that after reading projections about the majority-minority, white people were more likely to report having negative feelings towards racial minorities, support restrictive immigration policies, and express the fear that “whites would likely lose status and face discrimination in the future.” I wonder if the gentleman who confronted me after my talk in Richmond didn’t need research to tell him this was true.

If the article’s first point makes me feel hopelessly naïve, the second point makes me feel like an idiot. When I talk and write about foresight, I cite demographic trends as the kind of stable, reliable data that supports accurate forecasts. In the introduction to TrendsWatch 2017, I wrote, “we can use historical rates of birth, death, immigration, and emigration to forecast the demographics of a country’s population in 10, 20, or 50 years’ time. Factor in other data (young people may be delaying childbearing; vaccines may reduce childhood mortality) and we can make pretty accurate projections.”

Except (and as someone trained in science I SHOULD KNOW THIS) you get what you measure, and the way you define what you study shapes the results. Race and ethnicity are social constructs, not objective facts, and demographic projections reflect the way we divvy up humanity into segments. In other words it depends (as Tavernise points out) on “whom the government counts as white.” She goes on to quote political science professor Charles King’s observation that “race is about power, not biology. The closer you get to social power, the closer you get to whiteness.”

She also cites recent research showing that presenting the coming demographic shift as “the white category getting bigger by absorbing multiracial young people through intermarriage,” pretty much alleviated white anxieties. You can see this as depressing, reassuring, or both.

So we (as Americans) are faced with a classic dilemma of science: we want to find out about ourselves, but the very fact of doing that research—the way we ask the questions and report the results—changes the system, and not always in good ways. In this case, it may be triggering paranoia and fueling racism. There are good reasons to conduct an accurate census: to budget for future needs, to ensure fair representation and allocations of resources, to help us understand who we are, as a people. But the questions themselves have the potential do damage. (Case in point, a proposal to add question about citizenship to the 2020 census, which is currently being challenged in court.) How can we gather the information in a way that does no harm?

I’m thankful to this article for making me question what I thought I knew to be true, even though that means confronting some hard realities, both about human nature and about my own blind spots.

The underlying point I’m trying to address about demographic change is still valid and important: as our communities change museums have to change as well if they are to remain valued and useful. And demographic data, however imperfect, suggests that we are losing ground.

But clearly I need to rethink how I talk about this issue because words, and labels, have power.