Picture this: children and adults alike standing on the grounds of a museum on an early winter morning, sipping hot cocoa. Their eyes reach upward as they watch a three-foot spaceman created by the hands of an artist for this sole mission, flying into space, growing ever smaller, via a weather balloon. The scene may sound a bit unusual, but this unexpected event was actually a solution disguised as a spaceship.

Experimental technology, like this art-launching weather balloon, can be used as a tool to solve pressing institutional issues, such as connecting with communities in relevant, engaging ways, and empowering staff.

The range of technologies and ways to apply them abound, and it might seem daunting to determine which ones to pursue at first. Institutions should let their goals and challenges guide the decision. “Let the problem dictate the technology,” says Shane Richey, creative director of experimentation and development at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

In his role, Richey is responsible for pursuing experimental technology projects and developing new ideas for creativity and innovation at Crystal Bridges. Each component of the museum’s experimental technology initiatives, while still largely in development and constantly evolving, came about as the answer to a bigger issue, as Richey can tell you. Crystal Bridges has made it a priority to focus on accessible technologies which can be replicated as solutions to similar challenges other institutions are facing. Here are a few examples.

Problem: Marketing and promoting the museum

Solution: Surprise and delight visitors with new technology experiences

As mentioned, the launch event, Art in Space, came about as a solution to several issues. Crystal Bridges wanted to find an engaging way to promote the upcoming exhibition Men of Steel, Women of Wonder, which examines art-world responses to Superman and Wonder Woman. Superman was from space and crash-landed on Earth. This project came about as a fun opportunity to capture that concept, highlight an artist’s work, and do something new and exciting all at the same time. Artist Robert Pruitt created a small sculpture with the intent to send it to space on the weather balloon. The artist’s interest in science fiction, comics, and their intersections with Afrofuturism made him a fantastic partner in this project. The project also kept the artist’s voice at the forefront of the event, and allowed Crystal Bridges to reach a different, more science-oriented audience than an art museum might usually reach.

Museums can offer moments of “surprise and delight” like this by inviting the public to be in on the fun. By opening the Art in Space event up to the public, Crystal Bridges was able to engage the community in the museum’s activity, making them feel more connected to the institution while, at the same time, stimulating their interest in the museum’s new temporary exhibition in a unique way. This energy gets people engaged in what the museum is pursuing and makes them more likely to visit to see what’s next.

Another example of a “surprise and delight” experience came in the form of augmented reality. AR was recently featured in the focus exhibition In Conversation: Will Wilson and Edward Curtis, which examines the ways in which Native Americans have been photographed over the past century.

With the help of AR technology from Layar, a gallery viewer could hold his or her phone up to select photographs in the exhibition, and the subjects would come to life and talk. While this was not something viewers expected before walking into the space, they have received it well. Most visitors are surprised and delighted to find this extra dimension of engagement which was not made known before their visit, and this kind of surprise keeps visitors coming back to see what else is in store. It also encourages them to tell their friends about the exhibition—word of mouth, our favorite kind of marketing!

Problem: Maintaining visitor expectations of museum offerings

Solution: Use technology to keep artwork available

Virtual reality is another example of technology that came to Crystal Bridges as a solution to an existing issue. One of the museum’s most beloved and popular artworks is Kindred Spirits (1849) by Asher B. Durand. In the spirit of stewardship, the artwork has been lent out several times to other museums around the country.

During those periods, the museum would receive calls from guests asking where the painting was, upset that they would not be able to view it during their next visit. To find a solution to this problem that allowed Crystal Bridges to remain stewards in the art community, Richey began pursuing virtual reality technology as an alternative dimension in which visitors could interact with the painting, in a digital form.

“With VR, it was something that we felt there was interest for exploration – it allows us to do things that aren’t possible with the physical work of art,” said Richey. “It helps us create a deeper layer of interaction for our visitors.”

VR allows guests to go even further into the painting, adding an extra layer of dimension and a deeper level of connection with it, as seen in the video below. This demonstration has since been used at conferences and community events, and the VR program is being expanded to other artworks in the Crystal Bridges collection, such as Winter Scene in Brooklyn by Francis Guy (1820).

Problem: Providing new and unique visitor experiences

Solution: Use your museum to research and test new technology before making it public

At times, it might be difficult to determine which new technologies are going to work for your museum and your guests. Institutions sometimes pour hundreds of thousands of dollars into technology programs that ultimately do not move the needle on attendance or engagement goals. Why? Most often, it’s because technologies are rushed to market before they are made intuitive for users. For that reason, it’s wise to use museum assets to test out new technologies as prototypes before making the call to offer them to the public.

“[At Crystal Bridges], we’re trying to achieve experience, learning, and understanding of what technology can do for our visitors,” said Richey.

That is the thought behind a new experimental technology prototype being tested at the museum: an audio immersion experience, with support from a grant from the Knight Foundation Prototype Fund.

The audio immersion prototype will be tested on the museum’s upcoming temporary exhibition, Men of Steel, Women of Wonder. It will consist of a pair of specially designed headphones connected to a pocket-sized device which plays audio that immerses the gallery viewer in the world of whichever artwork he or she chooses.

“What we’re hoping is that this will allow us to create a soundscape that will allow the painting to behave like an open window into the scene that is being portrayed,” said Richey.

So, for example, if a visitor is standing in front of George Washington by Charles Willson Peale (1780-82), they will be able to hear a soundtrack of horses, muskets firing, men at battle, and other noises reflecting the scene of the artwork. Or perhaps one of Washington’s speeches could be recreated and recited. The point is to create an all-encompassing immersive experience.

If the prototype is successful, Crystal Bridges will be able to provide new audio-based interpretations in the gallery that will allow visitors to interact with new content and indulge a new sense. But the point of this early prototype is to walk before running.

“The goal of this is to learn something before we make it accessible to the public,” Richey said.

Problem: Keep staff members engaged and thinking creatively

Solution: Carve out gallery space just for them

It’s important for museum leaders to create time and space for their staff to express their creativity and innovate, even if their ideas are experimental and unproven. “The best way to empower museum staff is to allow them to have ideas and make them feel like they have the ability to pursue those ideas even if you as a leader are not sure about them,” said Richey.

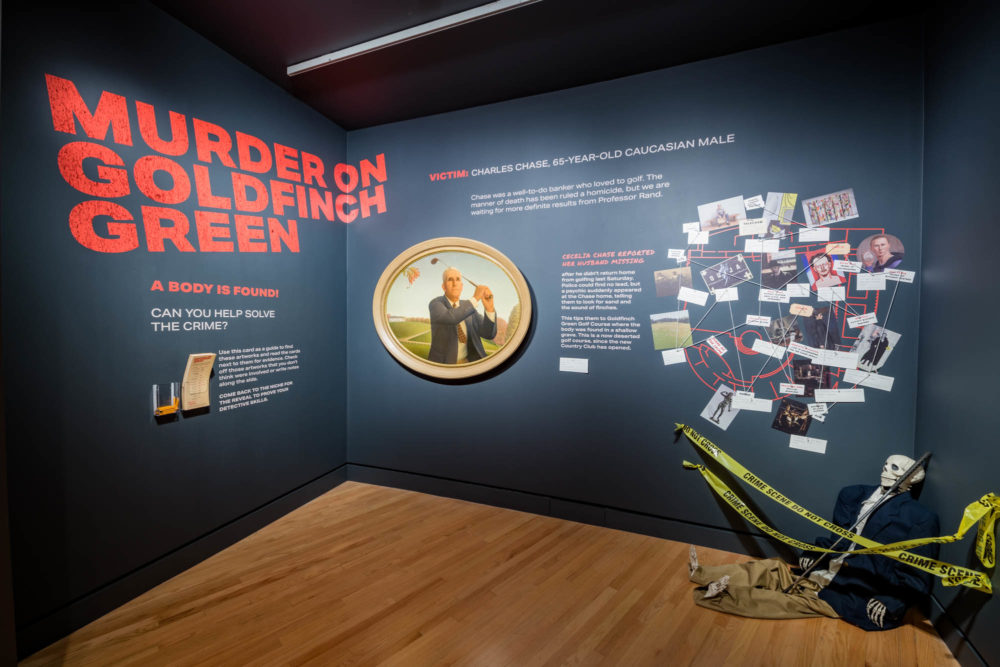

Innovation can come in many forms beyond technology. For example, at Crystal Bridges there is a small corner of the museum’s Early American Art Gallery named The Niche. The content in this corner changes every month to demonstrate the consistent churn of new ideas being explored at the museum.

All of the content and themes in this space are created by Crystal Bridges staff members, who pick their projects solely based on their own passions and ideas. In 2018, The Niche hosted everything from a gallery murder mystery, to an interactive Spanglish game, to a self-portrait station, and more. This isn’t an example of experimental technology, per se, but it is experimental nonetheless, and is a low-cost, high-touch, and efficient way to solve larger institutional issues. Not only does this provide a creative outlet free of restriction for staff, but it also offers a fun and engaging visitor experience—win-win!

Problem: Exploring technology with a limited budget

Solution: Seek funding in the form of tech-specific grants and pursue low-cost projects as a start

Budget and resources are very real things. Crystal Bridges, as a public nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization, is cognizant of this reality, and the key to allowing staff to pursue innovation without losing revenue is to keep costs low.

Spaces and projects can be created at minimal cost. With the Art in Space program, for example, the vast majority of the budget went to artist fees, since the artist was commissioned to create an artwork just for the occasion. Without the participation of an artist, the technology to send an artwork to space would put the budget somewhere between $500-$1000.

Another way to seek funding, for projects that need bigger budgets, is through the help of grants that specifically fund preliminary ideas.

The audio immersion prototype project, for example, was made possible by a grant from the Knight Foundation Prototype Fund, which helps tech innovators develop early-stage ideas quickly.

“What comes along with this is coaching, and the permission to build a prototype that may not work at all,” said Richey. “They are funding a proof of concept which could then be scaled up later. They also encourage us to take an open-source approach to how we develop this technology.”

So, not only would this allow for the grantee to build and experiment with a new project, but the fund also grants access for other institutions to learn from the experimentation.

Conclusion

When used correctly, experimental technology can be a powerful tool for solving some of your institution’s most pressing challenges and reaching its highest goals. Having accessible technology that answers today’s problems also allows museums and other cultural institutions to stay ahead of visitor expectations and become a source of continuous innovation.

As for Crystal Bridges? Who knows? Perhaps in a few years we’ll be taking art under the sea or creating gallery robots. If it helps us to be problem-solvers, we’ll never rule it out.

Excellent (and very practical) information here, I’m happy to see that such innovative approaches are being documented and shared abroad.