A few years ago, I had the unique opportunity to work across four fiercely independent and starkly different museums in the fine arts, sciences, and natural history. After being awarded ACLS Public Fellow with the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, I was invited to find creative ways of leveraging the institution’s enormous assets and expertise across the arts and sciences for the benefit of its audiences. The resulting initiative, branded “Carnegie Nexus” in 2016, has broadened my thinking about a museum’s public, a curator’s authority, and what is really at stake in developing interdisciplinary programs.

The conclusions I reached resonated with some of the authors I was reading at the start of the project. Authors like John Dewey, a great American philosopher and a major voice in progressive educational theory, who was writing at a time when education was stuck in rigid divisions, between fields of expertise and between the roles of student and teacher. He proposed that the ideal school was in fact not a school at all, but a museum. He found the epitome of his new progressive and “democratic” model of teaching in the way learning happened in museums.

For Dewey, museums offered a new approach: a direct experience with the object. And with that direct experience came a new set of values: the value of cultivating individuality and expression, and the free activity of the learner rather than the external imposition of a finished product determined by the text or the teacher.

The finest examples of museum design today—from exhibition to education—are built around a similar vision of the active participation of the visitor. Based in principles of progressive education, they present knowledge as something to be deliberated and co-constructed. They seek to support and repair community through a politics of recognition and inclusive representation, to ensure a sense of belonging from which genuine participation, contribution, and criticality—read, citizenship—is nourished.

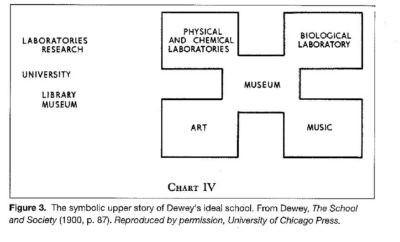

When I think of Dewey’s democratic ideals for American education, I think of his vision of a hybridized museum-school. In a series of lectures he wrote while teaching in Chicago, he described a sketch of this building as “not our architect’s plan for the school building we hope to have; but . . . a diagrammatic representation of the idea which we want embodied in the school building.” In this figure, you can see what would have been the top floor of a multi-storied building where the fields of knowledge at each of the four corners change or morph according to what is appropriate for the age range. But what unites them is what’s at the crossroads: the museum. Look at how the museum is at the nexus of disciplines or practices. You can go from the museum to anywhere and from anywhere to the museum. To get from one specialty or corner to another, you have to pass through the museum.

The site of the museum is a site of passage, connection, and translation. For Dewey, the museum represents the nexus of these different ways of doing, seeing, and speaking. To speak from that nexus is to speak publicly, to cast oneself not (merely) as a specialist in one’s particular field of study but as an intellectual who must teach from the full breadth of education as reflected experience, education that has not ended at graduation, or been confined to a discipline.

I wonder if more than a few of you are asking yourselves whether your museum is truly a site of intersection between ways of doing, seeing, and speaking, or if the culture it maintains is contentedly monoglot; whether your museum actively works against the confines of disciplinary borders or whether it is comfortable in the common jargon of its audience identity. A group of curators who were working across the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, a family of four fiercely independent museums of art and science, were likely asking themselves the same questions when they invited me in as a “catalyst.”

In 2015, I left Scotland after completing my PhD with the Center for Modern Thought at the University of Aberdeen. Still feeling the heady effects of my deep research experience, I arrived in Pittsburgh to the venerable institution built by a fellow Scot, Andrew Carnegie. The Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, or CMP, is a very complex organization that includes the Andy Warhol Museum, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Powdermill Nature Reserve, the Carnegie Museum of Art, and the Carnegie Science Center. A nimble group of staff composed of folks from each museum presented me with their charge, at once ambitious and open-ended:

- Catalyze cross-disciplinary activities between the four museums that leverage assets across the arts and sciences for the public good.

- Look for ways to foster and mobilize habits of collaboration internally.

Charge #1 was basically Andrew Carnegie’s founding mission—namely, that the museums should afford “liberal arts for the people”—which told me that somehow, they must have fallen away from this original vision. Charge #2 makes me think of what CMP’s former president asked of me: “Change the way we work.”

Let me say here that while this experiment was welcomed by the president, and the project was incubated in that central office, this was absolutely not a top-down initiative. The CMP had been unsuccessful at implementing that in the past, and had not found a way to encourage collaboration over competition between the museums. In my case, no one had to participate and I had no authority—in the sense of force or rank—to call people to my team. When I came up against these limitations, I was told repeatedly, “You are not a curator; you are a catalyst.” It took me a while to appreciate the distinction, but thanks to a colleague in natural history who retorted that, as a catalyst, my job was to effect a change in the very culture of curation, I began to look at this title and its possibilities differently.

As a catalyst, I was that agent that had to create an explosion—or at least a spark—between otherwise inert reactants. I had to be the match…the phosphorus. That is the chemical definition of a catalyst. Politically, not being a curator actually freed me from precisely the structures of power and recognition, and the well-trodden lines of communication, that enforce the same ways of doing and thinking and speaking. I say all this here because this is part of what is at stake in cross-disciplinarity: authority. People often eschew collaboration when they sense a threat to their authority, an authority grounded in exclusive expertise and intellectual turf. I hope anyone reading this can appreciate just how daunting the project was. It is hard enough to get different departments within one institution working together. But to bring members from four entirely different museums—each with its unique audience profile, distinct curatorial culture, and often singular economic model—to collaborate? This is a different beast altogether.

The advantage of being a catalyst was that I was neither kin nor enemy. I was the stranger outside of any identifiable order of power with whom people often shared their secret wishes, highest hopes, and deepest frustrations concerning the museums, their pedagogies and their publics. We shared our questions too, questions on the very nature of cross-disciplinarity, beyond the well-funded rhetoric that enjoins educators and researchers alike to advance STEAM efforts purporting to bridge the arts and sciences. (That bridge is usually constituted by turning the arts into a communicative instrument for the core principles and investigations of science.) We looked to the academy and the myriad of emergent disciplines like geo-aesthetics, mytho-poetics, bio-politics, pharmacogenomics, medical anthropology, area studies, memory studies, and of course…museum studies. This hybridized landscape reminded us that disciplines are in no way “natural;” they are historically constructed; they are materially and discursively maintained; some expand, others are colonized; some die and some are resurrected. Bridges between the arts and sciences were part of this landscape but for the Carnegie Nexus project, I was interested in deeper intersections—intersections that are philosophically necessary, and even tectonic.

Why tectonic? Tectonics are about deep foundations and deep ruptures. Foundations that, while invisible, are holding up or “grounding” the very distribution of what we can see; foundations of the history of ideas that invisibly govern what appears as conflict or consensus between disciplines from above. Ruptures represent the site of fluid possibility, a force and sometimes a catastrophic shift. Thinking tectonically, Carnegie Nexus tried to show how the arts (understood here in the broadest sense), rather than being a subordinate instrument or decorative respite, are actually driving sciences to develop by generating better questions, and troubling the conflation of truth with empiricism. Because often what matters cannot be counted, and what can be counted doesn’t truly matter. Carnegie Nexus tried to show how the sciences are part of a genuine conversation that instigates and inspires the aesthetic and political imaginary.

So, there I was, fresh from my PhD—which is to say, full of wonder, eager to listen, and eager to share. I was reading broadly, writing voraciously. I was attending the events at every museum nightly. I was meeting everyone I could at the museums and at the two distinguished universities at our doorstep: The University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University. I met people at speaker series at the University of Pittsburgh’s Humanities Center and Global Studies Center, student art shows at Carnegie Mellon, research talks at the Natural History museum, exhibition tours at the Museum of Art, live music at the Warhol, and family workshops at the Science Center. I never said no. My office walls were covered in pinned notes and articles with thematic ideas, authors, artists, films, diagrams, maps—all trying to draw forth the urgent questions of our time in unexpected ways that engaged the public with research and figured out how to embed that in platforms and venues the museums already had in place.

Thankfully, Ben Harrison, the curator of performing arts at the Warhol, joined me in choosing from these many pots on the stove and formally proposing to all our stakeholders what would be our pilot public program series. We decided on twelve events on the Anthropocene—the geological epoch proposed by atmospheric chemists who believed the earth’s core systems were now dominated not by natural forces but by anthropogenic, meaning human-driven, ones. To the four core systems that planetary scientists recognized—hydrosphere, lithosphere, biosphere, atmosphere—a fifth was added by critical theorists: the techno-sphere. Ben had introduced me to the work of a dozen performance artists who draw striking relationships between society and environment—artists that would be well suited to the Warhol’s Sound Series but, he thought, so much better framed within a public curriculum on the Anthropocene. With the devoted backing of curators and research scientists, we launched the series, and entitled it Strange Times: Earth in the age of the human. Strange Times put the liberal arts—as Andrew Carnegie knew it—at the generative center of a searching discussion on climate crisis.

Video design: Clear Story Creative

We hosted avant-garde theater performances, documentary film screenings, and appearances by literary giants, roboticists, philosophers, musical composers, evolutionary ecologists, political economists, digital animators, herpetologists, and cultural anthropologists. I started with the premise that the Anthropocene was an idea that belonged to no one but changed everything. Although the term was coined by an atmospheric chemist, the idea has surged across the humanities for over ten years, and has shaped or advanced emergent disciplines: political ecology, environmental humanities, and ecocriticism, to name just a few of the new mountain ranges. (Tectonics.)

Driven by the question “Will we survive ourselves?”, each program began with a signature opening. Lights would go out and the techno/bio-acoustic sound piece that Ben had commissioned composer Jayce Clayton to create for our series played at an evenly increasing volume. While the audience was immersed in a manipulated chorus of migratory birds, we screened the verses of the “Ode to Man“—the famous chorus in Sophocles’ Antigone which held the key to the series title.

There is much that is strange, but nothing

That surpasses men in strangeness.

Yes, Sophocles. Scientists came up with a word for the planetary epoch of the human, but humanists have been thinking about “nature” and the catastrophe of our arrival for over three thousand years. The series was coursing through questions that were grounded in the understanding that the ecological crisis is a symptom of something bigger, deeper, older: our alienation from labour, our colonization of nature, our enslavement of each other, our crisis of humanity—a crisis that was written in the lithosphere like an epitaph, a crisis that had been warned of in ancient Greece when theatre and politics were played on the same stage. Strange Times allowed artists and scientists to gain a new perspective on their own work and draw from the audiences’ reflections on the bigger issues that concern us all.

The public filled the house every week for the four-month course of this experimental pilot and their response to Strange Times was astounding:

“Wonderful! Wish it had been longer—It’s so refreshing to see information presented in a way that is bold and complex, not soundbites”

“I came for the confluence of art and science. One illuminated the other and vice versa in a most stimulating way. I found the event more thought provoking than I expected.”

“Fantastic! Art and science are not isolated pursuits in the real world. Their symbiotic relationship needs to be exalted and explored—especially by the Carnegie!”

“Thank god you are keeping up the intellectual through-lines. You can really see how it all connects. I love that you are not watering it down”

The CMP, without a doubt, was uniquely poised to explore the complex and necessary intersections across fields of knowing—and not (only) because it was composed of “four corners” but because the museum is public facing. As such, any museum must attend to the questions and concerns, the fantasies and forgetfulness, the collective pains and buried stories of the public, directly. This public purpose of the museum to generate publicly oriented knowledge certainly does not mean “dumbing down”— I hate that haughty term with a passion. It treats the public with contempt. Visitors are invited in but nevertheless always feel outside, excluded. And I would add that on the other side of “dumbed-down” is the term “academic”—especially as it is used in the American context. Sceptics of Carnegie Nexus used the term “academic” against our project many times—all I could hear was the same contempt, as if thought itself was not meant for the public, as if “a liberal arts for the people” was elitist.

There is a nearness to the academy that the museum should foster. But at the same time it cannot, it should not, be a facsimile of the modern academy, with its largess of knowledge that is channeled through defended repositories of expertise practicing an ever-increasing involuted monologue. Nor should it imitate the academy’s hierarchical divide between research (read, “curators”) and teaching (read, “educators”). Museums can be freed from these narrow ideas of knowledge and stultifying hierarchies by way of their public-facing priority. I have joyously spent the last twenty years conducting research, designing spaces of learning, and teaching in both museums and universities—and I have loved them both. I have seen every evidence point to how museums can take the highest ideals of the academy together with their uniquely public position to draw throughlines across the arts and sciences in ways that bring the vitality of both to the fore, in ways that extend the limitations of existing thought, and—crucially—in ways that diversify, surprise, and cross-pollinate audiences. For that reason, it is such a pleasure to hear from people who attended the series that they came both to enjoy British avant-garde theatre and to grasp the existential dimensions of ecology, or that they came for the robotics engineer but were blown away by the philosopher. The excitement was palpable: academics across diverse fields, media, councils, and civic leaders; and most crucially, from the Pittsburgh public who described us as “a new way of doing museum.”

With Strange Times nearly sold out before we even started, Carnegie Nexus was extended beyond the ACLS fellowship, and the president asked me to “do it all again but in half the time.” Ben and I decided to take our now more-populous team to the Powdermill Nature Reserve to brainstorm the new season, whose theme we had chosen as a natural extension of the Anthropocene: migration.

Migration is arguably one of the most astounding phenomena in all of natural history—human and animal. It is a movement unlike any other because it shapes not only memory but metabolism; it informs our metaphysics and has a hand in morphology. Migration radically troubles any safe or final distinction between genetics and environment. After spending a day with avian migratory specialists at Powdermill, the Nexus team was inspired to sketch out possibilities for events and exhibitions on the art and science of passage. By the end of the month we had our title: Becoming Migrant…what moves you? By the end of winter we had our line-up and program booklet. Designed by the artists at Little Kelpie Creative, it was an ingenious cross between a personal passport and a biological field guide.

Video design: Clear Story Creative

Nine events were produced that explored how migration impacts those who move, the environments they leave, and the places to which they arrive. We hosted RadioLab co-host Jad Abumrad, international singer and songwriter Fatoumata Diawara (video), oceanographer and climate scientist Michael Mann, and The Refugees author Viet Thanh Nguyen. Through a photography exhibition, we explored the stories and experiences of multiple generations of Pittsburgh immigrants and how they make up a lens through which the larger story of America is seen and felt. We capped the series with an extraordinary performance of Agrupaciòn Señor Serrano’s Birdie (video). This new theatre piece was a cross between the game of golf, Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, colonial legacies, and the refugee crisis. The audience was immersed in a movement between the mirages of two worlds—one confounded by war, ecological devastation, and human smugglers; and one that enjoys sanitary dwellings, renewable resources, and a common welfare. Between the two was an unstoppable movement of all that exists: people, plants, animals, objects, and ideas. I will forever recall the collective’s description: “Stillness is a chimera. The only thing there is, is movement. If it is impossible to stop an electron, what’s the point in building fences against flocks of birds?”

Since the end of Becoming Migrant I have been approached by people from various backgrounds asking to participate in future plans with Carnegie Nexus: a professor of Global Studies, a professor of the philosophy of science, a school teacher, a poet, a luthier, a dairy farmer, a rabbi, and a public health research scientist, among others. It was with the arrival of people from every corner of practice and profession, that the driving question of the series, “What moves you?”—drove through me. Because at the heart of any devoted thought to migration is a thought of hospitality: that is, of the relation between host and guest, teacher and student, citizen and foreigner, self and other, museum and community; a thought of wanderlust, of homecoming, and of identity as nothing more than the sum of encounters; a thought, finally, of what our obligation is to the stranger. My PhD was on hospitality. I am sketching ideas for Nexus 3.0 and looking for a new museum (or university) to house it.

For those of you eager to stimulate passages across siloed fields of knowledge, eager to welcome the stranger’s question, eager to be a new way of doing museum, here are some things I have learned along the way: Recognize that the public is a gift to the museum and not the other way round. Be the site from where the public intellectual can speak. Be the nexus from which not only statements about what we know but genuine questions about what we don’t know are welcome. Cross-disciplinarity is more than just bringing disciplines together around some clearly delineated object of study. It’s about challenging those disciplines to reach out beyond their traditional purview in a way that makes them need the other. One of the common assumptions of cross-disciplinarity is that it is only as good as the rigor of the distinct disciplines that come together. But this is a misconception. Disciplines are stubborn things whose interest, at the end of the day, is to reproduce themselves. They do this through elaborate systems of constraints, rewards, and rituals. But research, in its phosphoric character, can astonish, not just confirm. And teaching, like tectonics, can transform, not just inform. When you think of what is at stake in cross-disciplinary work, recall the writing of Christopher Fynsk, another American philosopher who happens to run one of the world’s most prestigious cross-disciplinary universities, the European Graduate School:

“Every thinker will discover that rigorous cross-disciplinary work on questions of crucial social import requires what ‘discipline’ can provide, but it is cross-disciplinary questioning that defines most effectively and meaningfully what is required of a discipline.”

Thank you for this inspirational and highly motivating article!

I am embarking on a journey to join a history museum and a museum of natural history into a new interdisciplinary organisation – also a museum, but hopefully one with a new focus on our visitors, surprising them with new perspectives, and questioning what we know about science and history.

My additional challenge is that we are a much smaller organisation with few resources… which may still lead us to creative results!

Thank you Almut! It is always a pleasure to hear back from ‘the great beyond’ of on-line publishing and to join in solidarity those in the field of the public humanities. This year has been a particularly difficult one- Carnegie Nexus proved too much for the Trustees to support and so they dismantled it. I only wish that there were enough hours in the day to have also secured funding for it so that I might be left free of their poor judgements and disservice to the public. But it is a glorious thing that you are embarking on– I think that this work you and I have done could be something to offer the AAM as a book of collected essays and interviews. Good luck to you! -edith