“It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards,’ says the White Queen to Alice.”

― Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass

In today’s post, I’m going to introduce you to backcasting, a planning method that helps people and organizations figure out how to create their preferred futures.

Commonly, when people hear “futurist,” they think of forecasting—the process of extrapolating what future could be created by the forces shaping the world today. Forecasting is a valuable tool—it helps us imagine a “probable future” that might come to pass if we don’t take deliberate action to correct our current course. Backcasting flips the process, starting with a vision of what you want the world to be, and identifying actions you could take to make this future come true.

So (to riff off Lewis Carroll) in backcasting you use your imagination to remember what will happen to get you where you want to be. Yeah, dwell on that sentence for a minute.

Backcasting is a useful tool in the foresight toolkit because it helps people realize their own power as agents of change. While foresight sometimes paints a bleak picture of the future (“climate change will render the city I live in practically uninhabitable in 50 years”) backcasting can engender hope, and inspire action (“here’s what I can do now to combat climate change, and increase my city’s resilience.”)

Backcasting also:

- Helps sensitize you to signals of change (things actually happening in the world today) that might help create your preferred future

- Encourages you to find or create preferred options, when it comes to planning, policy, or advocacy, rather than just settling for the available choices.

Last month I conducted an abbreviated version of backcasting with some of the 300 delegates attending Museums Advocacy Day*. (Hi guys! Love you.) Barry Szczesny, AAM’s director of government relations and public policy, kicked off the session “Building the Future of Education: Where Are We and Where Do We Want to Go?” with an overview of current policy issues. Then I lead attendees through 45 minutes of backcasting long-term advocacy goals.

Working from the “Bright Future” scenario presented in TrendsWatch 2018, delegates debated what policies, at the state or federal level, could lead to a future in which:

- Primary education takes place throughout the community

- Primary education emphasizes creativity, collaboration, social IQ, cross-disciplinary thinking

- Regulatory reform has lifted the burden of student debt

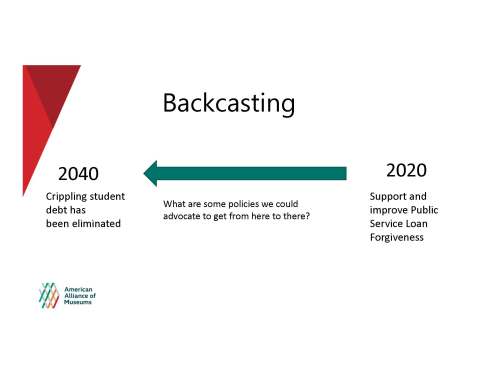

Take student debt: today about one quarter of American adults are paying off student loans. On graduation, the average student borrower has  $37,172 in student loans, which is $20k increase since 2006. What policies could help ensure that by 2040, graduates don’t enter the workforce hobbled by the loans they took out to finance their education?

$37,172 in student loans, which is $20k increase since 2006. What policies could help ensure that by 2040, graduates don’t enter the workforce hobbled by the loans they took out to finance their education?

Long term proposals that might effect this change include providing free college tuition or increasing grants or subsidies. (Mind you, there is a great deal of thoughtful debate about these issues—more than I can summarize in a short post.)

Short term, we can identify current policy proposals that might be steps in the right direction. For example, the Alliance’s advocacy around higher education includes urging Congress to support and improve Public Service Loan Forgiveness and sufficient income-driven repayment options for federal student loans. (See AAM’s Higher Education Issues Brief.)

Progress can begin at the state level as well, as initiatives are launched, tested, and provide models for similar efforts in other states. One of our delegates pointed to California’s recent plan to combat student debt by providing grants to community-college students and subsidizing their first year’s tuition. Myself, I am eagerly watching the implementation of Vermont’s Act 77, which charges secondary schools to provide personalized learning plans and flexible pathways to graduation and (I hope) opens the doors to students receiving academic credit for learning in nontraditional settings—such as museums.

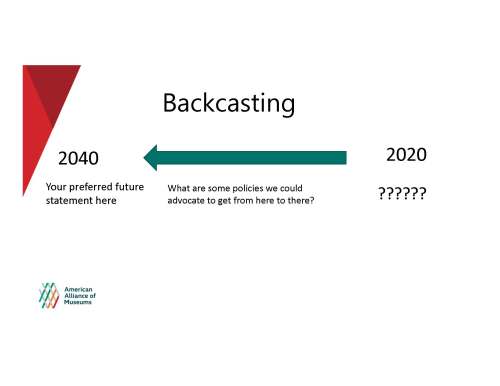

If you want to try backcasting at your own organization, here is one way to start.

- Download and share TrendsWatch 2018 (free PDF copies available on the Alliance website).

- Pick one of the four scenarios, each of which describes one version of the year 2040, to read and discuss with colleagues.

- Choose one plot element you find particularly intriguing, inspiring, or frightening.

- Set aside some time (I recommend 45 minutes to an hour) to work backwards from this statement, envisioning the steps that in that future, led us from here to there.

- If you discussed a plot element that you feel reflects a desirable future, conclude the discussion by identifying one or more things you could to, as individuals or as an organization, in the next year, to start down that path. If you chose an element of an undesirable future, identify what you could to AVOID taking the first steps in that direction. Each time I’ve done this exercise, the resulting conversations are deep and provocative, leaving me with new insights on how museum people can shape the future.

If you try backcasting at your organization, I’d love to hear about it—what subject did you tackle? What ideas did you generate for what you, your museum or your company might do to make the world a better place?

And if you are interested in trying out other foresight exercises, sign up for the Futuring Workshop I’m teaching at the AAM annual meeting this year, on the afternoon of Wednesday, May 22. I’ll be sharing tips, templates, and sample agendas that I hope will encourage you to organize some futures activities for your colleagues back home. The $50 fee covers materials, handouts, snacks and AV fees. Enrollment is limited to 50, so you might want to sign up soon.

*At Museums Advocacy Day this year, 300 museum advocates made 365 visits to Congressional offices and took Capitol and social media by storm. Check out #museumsadvocacy2019 to see posts from advocates and legislators, join the cause today using our updated Advocate from Anywhere tools, download and share the updated Museum Facts Infographic and see recent Alliance Advocacy Alerts to learn more.

There’s a lot to admire in this analysis, but your starting facts about college student debt need some adjustment. At the end of the 2016-2017 academic year, the average debt held by new bachelor’s degree recipients who had ANY individual student loans was $32,600 if they graduated from a private, non-profit college or university and $26,900 if they graduated from a public four-year institution. However, only about 60% of the graduates held loans, so the average debt per degree earned — which may be a better social indicator — was just $20,000 or $15,500, depending on the type of non-profit baccalaureate institution. This is according to data collected by The College Board for its annual Trends in Student Aid report (https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/2018-trends-in-student-aid.pdf). There are some caveats to the data, which are limited to certain types of loans and do not account for students who take on debt but fail to complete a bachelor’s degree — who are, in many cases, the worst served by the American higher education system. However, these numbers underscore the fact that the large majority of bachelor’s degree recipients actually graduate with a manageable debt load, if they have any student debt at all. (The burden of graduate degrees is another story!) For more contextual information, I encourage my museum colleagues to consult the The College Board and “Student Debt: Myths and Facts” from the Council of Independent Colleges (https://www.cic.edu/r/r/Documents/Student-Debt-Fact-Sheet.pdf).