When you visit a museum, do you feel empowered? Do you feel like you have authority and control of your experience? That’s why Marabou is here: to remind us that we all have agency in our museum experiences.

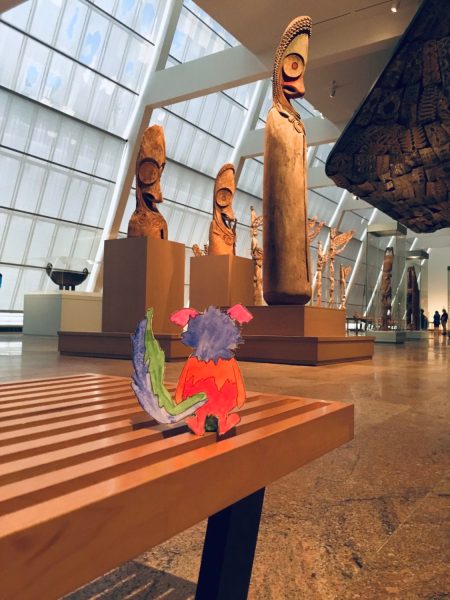

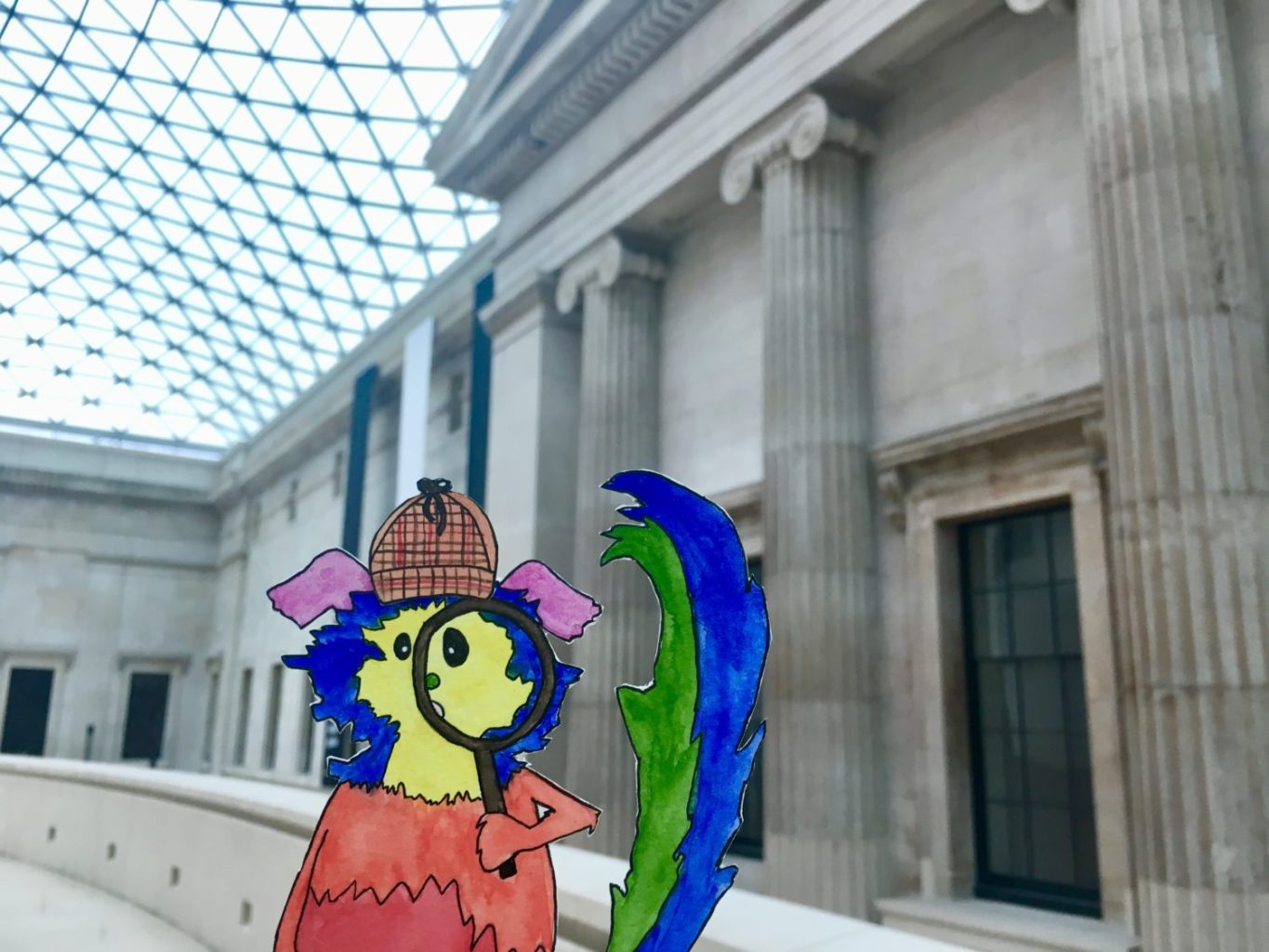

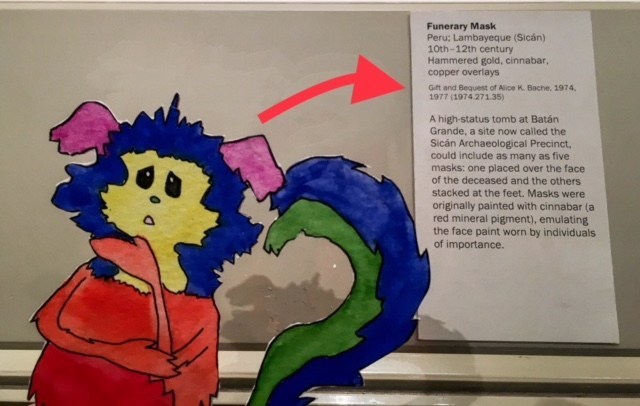

Marabou is a rainbow-colored creature with fluffy purple ears, a blue and green bushy tail, and tufted red feet. Marabou uses the pronouns they/them and is ageless. I created Marabou as an avatar and entry point for looking at museums with a critical eye, and for facilitating deeper interactions with museum content and practices. Marabou is intentionally cute and disarming, designed to be appealing to a variety of audiences. At first they grab attention with their striking appearance, but eventually they’ll lead readers and viewers to focus more on what is being said than who is saying it. Marabou asks questions and provides commentary, but most importantly gives examples of how we can engage with and think about museums differently from the manner in which many of us were taught. As global social and political tensions increasingly manifest in the museum world, I felt there was a need for a resource like Marabou at the Museum.

Museums and cultural sites are experiencing a period of upheaval. Established curatorial and interpretative practices are being called into question, both externally by the public and internally by institutions putting in the effort to do honest self-critiques. Criticism of museums is increasingly making headlines in mainstream media, especially in relation to issues of representation, acquisition, and repatriation. As I read these often catchy, sensationalist headlines, I wonder if the general public is engaged and invested in how museums are dealing with these issues, or if they just shake their heads and swipe to the next news item. I was curious to find out why many people fall into the latter category.

I think museums hold a special place for people, particularly in a nostalgic sense. Most of us are brought to museums as children, and we either love them or hate them at first exposure. I believe more people of all ages and backgrounds would like museums and be invested in issues of accessibility and representation if they felt like they had some type of agency within them. From those early trips as children (and stemming from the inception of the museum as a construct and means of social conditioning) we are taught that we go to a museum to learn and that it presents indisputable facts. We are taught that museums are bastions of information; we are meant to absorb as much from them as we possibly can, not debate or challenge what we see.

Growing up in New York City, I was privileged to access some of the most prominent museum collections in the world. As a child, the halls of a museum were hallowed. As an adult and graduate student, I was filled with nostalgia and gratitude as I studied their contents. But somewhere in grad school my attitude towards my beloved museums changed. I started to question the comfort and nostalgia I felt walking through their galleries. The content and design of them had changed minimally, if at all, presenting the same things I had seen when I visited as a child, twenty years before. My sense of nostalgia was shattered by an adult understanding of colonial narratives and the lack of representation in all aspects of museum operations and display for Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color. Unsettled by seeing the same old, incomplete, Euro-centric, heteronormative, white narratives told to me as a child passed on to the next generation, I was inspired to find ways to constructively critique and change the institutions I had grown up loving. My blog Marabou at the Museum is a resource for considering the museum through a critically engaged lens. Marabou is meant to change an individual’s experience in a museum, whether they work there or are just visiting, by:

- Acknowledging that museums are not enjoyed by everyone and that there are ongoing issues of representation and accessibility,

- Reminding that we each have individual agency to ask questions about and challenge all aspects of the museum,

- Providing a new framework and tools to analyze and reimagine the museum,

- Continually searching for and reimagining ways museums can be more inclusive, socially responsible places.

The tagline for Marabou at the Museum is “working toward equity, inclusion and justice in museums & cultural spaces.” All posts are written through the perspective of Marabou. The focus is not on Marabou, but on what they are saying. Granted, Marabou is meant to be cute and catch your attention, but Marabou is really a medium, a lens through which people can look at a museum experience, like an exhibition, differently. As an educator in both university and museum settings, I know people can sometimes associate museums with less-than-inspiring experiences. My hope is that a creature, a messenger, like Marabou can be engaging enough to open conversation about museums to many people, especially those who may not have thought about museums as participatory spaces.

Even though I am someone who has loved museums since I was a child, I found greater love and interest for them once I realized that I could engage beyond exhibition text or an audio tour. Throughout my career I have performed a variety of roles in fundraising, curation, and education within the New York museum world. These experiences provided knowledge and perspectives that shifted the way I see museums. As I started taking an increasingly critical approach to my visits, I found myself more comfortable with posing questions to the museum. I bring this inquisitiveness to Marabou, presenting readers with multiple entry points for thinking about and experiencing the museum. From specific questions about incomplete and questionable provenance on a museum label, to broader questions about how museums can reinterpret the objects currently in their collections to fill in historical narrative gaps, Marabou prods and questions how museums can be better. Space is also given to highlighting when institutions take the initiative to correct structures and practices that perpetuate injustices.

Although I consciously work to make Marabou interesting and engaging to the casual museum visitor, I also see museum workers as Marabou’s audience. Marabou the character is a hybrid, both a museum visitor and a seasoned museum professional. Marabou offers the reader a chance to shift perspective, from employee to visitor and from visitor to employee. In the museum field, we are usually required to tightly focus in on a specific topic or task. But in museum practice, just like with the human eye, when you focus too hard, your vision strains. However, if you let your eyes relax and soften your gaze, you see differently. Marabou does both, vacillating from hyper-focused to macro thinking, asking pointed and broader questions that sometimes go unasked or have been deprioritized by museum administrators.

I created Marabou at the Museum as a resource that includes and listens to the many voices who are doing the work of reimagining the museum. Just as equally, Marabou is a convening point for dialogue among museum professionals, historians, activists, community groups, and the average museum visitor. My hope is that Marabou’s observations and questions spark conversations about museums within oneself as well as with friends and colleagues.

For example, the post “Object Labels at the Museum” invites the reader to think more critically about museum labels. Marabou looks at the complete label, starting with the name and where the object is from, and then goes on to consider content that is often overlooked. A label’s information is openly provided by the museum. It is an opportunity to learn more about the object and is a springboard for asking questions about ethics relating to ownership and a museum’s acquisition practices. The post leads with a thought: “Marabou wonders, if a museum has objects that have been acquired due to violence, war, and/or illegal means, is it the museum’s responsibility to explain this acquisition history to its visitors?” Perhaps you are a curator who has recently been laboring over your own museum labels, or maybe you’re someone who doesn’t look at labels. Either way, I invite you to read the full post to see if Marabou offers a new perspective.

Marabou wonders, if a museum has objects that have been acquired due to violence, war, and/or illegal means, is it the museum’s responsibility to explain this acquisition history to its visitors?

When visiting a museum, Marabou takes more time than the average visitor to read the museum label. You learn a lot from a label, the obvious stuff such as name of the object and artist (if known), materials, the country and/or culture of origin, and possibly how old the object is. Where most visitors stop reading, Marabou continues. They want to know the provenance of the object. Provenance is the history of the object, where it originally came from, and the record (if any) of who has owned it over the years.

Read the full post “Object Labels at the Museum.”

About the author:

Megan Elevado is a New York-based historian, writer, and artist. Marabou at the Museum combines Megan’s creative practice with her passion for history and material culture. Megan’s writing and analysis are informed by her experiences teaching at Parsons The New School for Design and working at cultural institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, and the Tenement Museum. Follow Marabou on Instagram, Facebook, and at marabouatthemuseum.com. Share your thoughts and suggestions for Marabou via email: hello@marabouatthemuseum.com.