The assumption that museums must be permanent buildings with physical collections is no longer sustainable. With decreased funding, increased competition, and the burden of care, museums have had to reimagine themselves. Some small museums, in particular, have rejected the isolationist, elitist model focused on collections and physical space in favor of community- and people-focused programs. Building on Georges Henri Rivière and Huegue de Varine’s “eco-museum” concept introduced in 1971, these museums use tangible and intangible heritage to provide context and inspire action on community concerns and social justice issues. Yet even as they challenge some traditions, many still rely on the physical museum model. The twenty-first-century museum—with its focus on serving people—does not necessarily need a physical presence to fulfill its mission. Among the pioneers of this model is my home: Girl Museum, the first and only museum in the world dedicated to celebrating girlhood.

Video featuring contributions from Girlhood Gang and Brittany Jae Wade

Girl Museum is doubly brave. Founded in 2009 by art historian Ashley E. Remer, it challenges the two traditional anchors of museums: holding collections and maintaining physical space. Entirely virtual, Girl Museum draws on open-access collections, partnerships with physical collections, and community contributions to research, interpret, and present projects focused on girls and girlhood. We are a curatorially collaborative endeavor, reinterpreting material about girls in existing collections to inspire social action that advances girls’ rights and welfare. Now in our tenth year, we have produced over thirty-three exhibitions and collaborative projects, piloted and promoted multimedia projects that enable emerging scholars and museum workers to share their research, and advanced initiatives to increase girls’ participation in society while granting them a safe virtual space to claim as uniquely theirs.

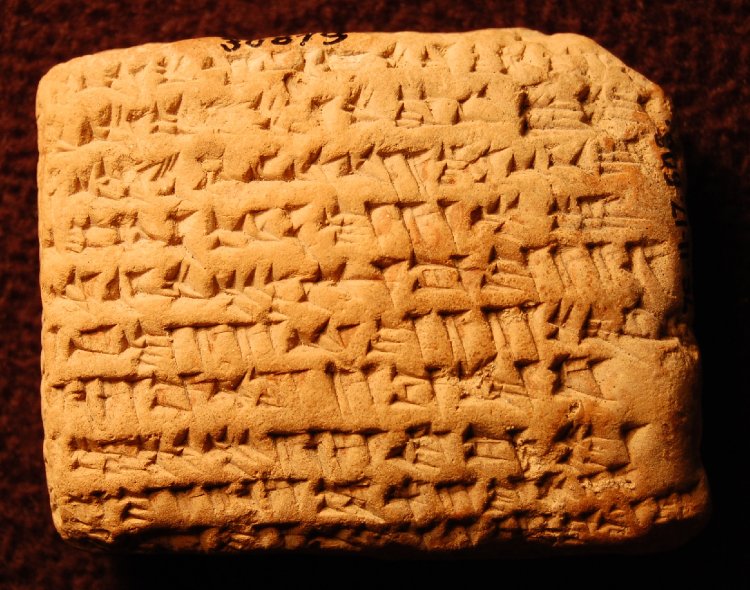

Skip over related stories to continue reading articleVirtual existence has been crucial to our mission. Rejecting the notion of “collecting” girlhood, and recognizing that so little work has been done directly on the topic to begin with, Girl Museum relies on collections in Creative Commons and held by other institutions to reframe conversations about history and culture. Exhibitions are organized around themes or historical moments, combining images of physical objects with scholarly research, oral and community histories, and public contributions, to showcase narratives that museums have long ignored. For example, our 2017 exhibition 52 Objects responded to the British Museum and BBC project A History of the World in 100 Objects, correcting the absence of girls in world history and demonstrating the broad range of their activity in everyday life and the common issues they have faced. Objects in our exhibition included Valdivia figurines from the Americas circa 3500 BCE, a Babylonian cuneiform tablet recording the sale of a slave girl, a Grecian bronze strigil featuring a girl athlete, a Medieval cassone (marriage chest), various paintings and textiles depicting girls, an Apache doll, Qing statuettes, and photographs of girl laborers and soldiers. Each is an intimate portrait of girlhood in itself that, when combined with all fifty-two objects, presents a story of world history not yet studied in depth.

Programs like 52 Objects allow us to be more inclusive in both with whom and for whom we work. Girl Museum partners with a variety of individuals and organizations. Led by a board of scholars and an all-volunteer Senior Team of nine women, with an average of 20 interns per semester, Girl Museum’s team includes emerging and established scholars in art history, museum studies, history, English, journalism, sociology, education, cultural studies, and other specialized fields. Additionally, Girl Museum works with organizations around the world—including Apne Aap Women Worldwide, GlobalGirl Media Network, Games for Change, She Shreds, Team Girl Comic, and the United Nations GirlUp campaign—to gather, preserve, and present girls’ histories and modern-day struggles. Notably, our collaborations with artists Emanuela Caso and darlene anita scott explore modern girls’ issues through art, while a collaboration with the American Poetry Museum produced Girl for Sale, an exhibition about and featuring stories of girls who were trafficked.

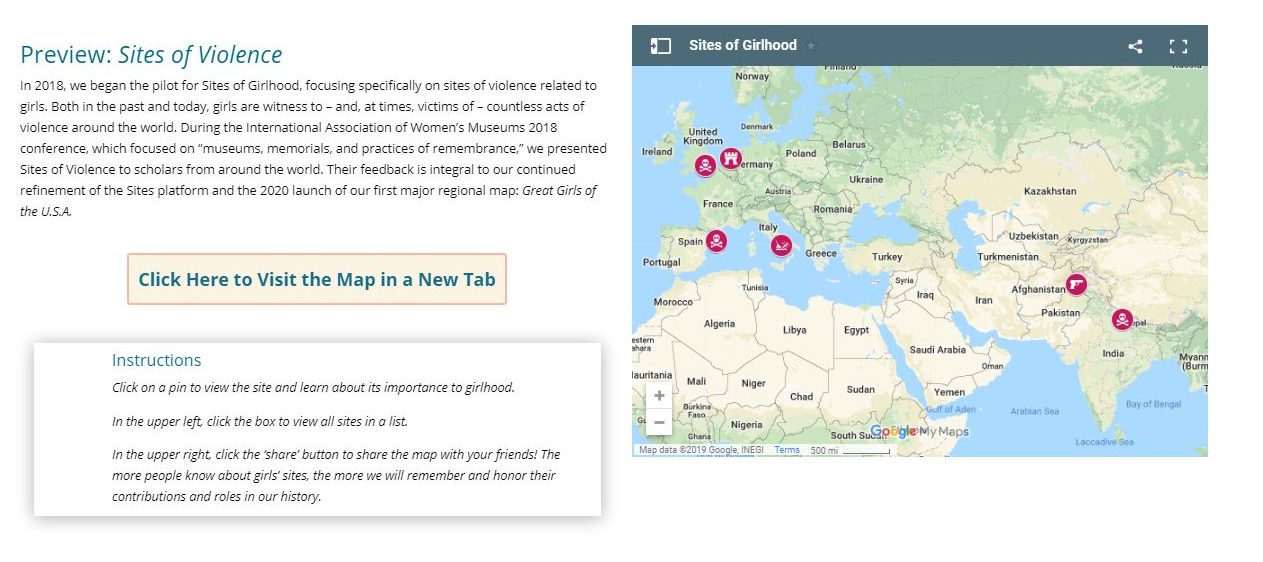

Being virtual also promotes inclusivity in who can visit: anyone with a computer and Internet connection. There are none of the common transportation, admission, or other barriers that come with physical spaces, and virtual technologies enable our team to implement accessibility and translation initiatives to increase access in real time. Additionally, virtual presence allows our bare-bones budget to remain dedicated to our core missions of program production and advocacy, with emphasis on including the direct voices of girls—in primary sources, interviews, contributed pieces, and multimedia—in all that we do. Thus, we are able to diversify the range of girls who we represent and fulfill our charge to advocate for every girl without being constrained by physical gallery spaces or artifact conservation needs. We are also able to welcome girls to contribute as soon as they visit, through guest blogs, podcast and exhibit contributions, artist-produced exhibitions, volunteering, and interning. Most importantly, girls can contribute to our ongoing GirlSpeak projects, a series of community-produced galleries inviting visitors to share memories, opinions, and thematic pieces that showcase the broad range of girlhood experiences and struggles. GirlSpeak projects include our ongoing podcast series and blogs produced by interns and guests; bi-annual Heroines Quilts that invite discussion of who and what constitutes a “heroine;” Why I Game, which features over thirty-five contributions to date advocating for a more inclusive gaming community; and Kiwi Chicks, a collaboration with National Services Te Paerangi to produce a database of girl-related artifacts in New Zealand. In 2020, we will premiere our largest collaborative project to date: Sites of Girlhood, a campaign to put girls “on the map” through an international database of historical sites and physical spaces where girls made—or were profoundly impacted by—history.

Girl Museum is a brave space—using the ever-expanding virtual world as a place where museums can exist and work collaboratively to benefit society. As such, it is a leader in how museums can use digital presence to showcase collections while fostering diversity, inclusion, equitability, accessibility, and collaboration as the new norm. Within ten years, we have built a place where visitors can participate in dialogues on how culture has treated, and continues to treat, girls. We leveraged the fastest-changing technology in the world to fast-track these changes in museums while remaining fiscally responsible, creatively open, and resistant to the elitist models that traditional “museum” definitions and spaces perpetuate.

With aspirations to create a global database for girl culture, to produce exhibitions and labels that challenge museum visitors with their own #TimesUp charge, and to empower girls using their unique history and culture, Girl Museum is paving the way for twenty-first-century museums. We envision a global network where museums no longer compete, but rather collaborate, to advocate for diversity, inclusion, equitability, and accessibility in ways our predecessors could hardly have dreamed possible.

Most of all, we envision museums that are as brave as those we represent. For all the girls who came before us, to all those who are changing the world with us, Girl Museum exists to preserve, protect, and draw on their heritage in order to make the world a better place. We brave the hackers, haters, trolls, spammers, and doubters to advance critical dialogues on how culture—and museums—treat girls. In so doing, we have opened new doorways to collections both on view and hidden in storage, in ways that demonstrate how museums can be critical, brave spaces for the twenty-first century. We hope you’ll join us.

About the author:

Tiffany Rhoades Isselhardt is a Public Historian who serves as Girl Museum’s Program Developer. She has curated over 15 exhibitions, leads production of podcasts, and collaborates with institutions around the world to advance girl culture and rights. She also serves as Fundraising Coordinator of the Kentucky Museum at WKU, and spends her free time researching, writing, and interpreting girls’ and women’s heritage in museum collections and historic sites.

*Girl Museum defines “girlhood” as the period of life between birth and twenty-one years old for female-identifying people. However, we recognize that definitions of “girlhood” have varied throughout time and across cultures, and in so doing, we commit to working directly with communities to define and interpret “girlhood” according to their own traditions. It is our belief that so doing is the most inclusive manner of ensuring girls are represented in museum collections and assisting the field of girlhood studies in reaching a global definition of “girlhood” in the future.

Comments