This is one of the five trends from the 2019 TrendsWatch. Click here to read more about the full report.

“The first generation of the digital revolution brought us the Internet of information. The second generation—powered by blockchain technology—is bringing us the Internet of value: a new, distributed platform that can help us reshape the world of business and transform the old order of human affairs for the better.” —Don Tapscott

Open your news feed and you are sure to see headlines featuring the terms Bitcoin and cryptocurrency. The underlying technology—blockchain—has been around for over a decade, but in the past year, there has been an explosion of experimental applications including refugee aid, educational credentialing, and provenance tracking. Because blockchain tech has the potential to transform major sectors—including finance, real estate, trade, shipping, and education—it’s important that people understand what the technology is and how it may impact their lives. This chapter provides a basic explanation of what blockchain is and how it works, an overview of how it’s being adopted, and an exploration of how it may affect the work of museums.

Description of the Trend

Despite all the press, blockchain remains a mystery to most people. A recent survey of the British public found 59 percent of consumers had never heard of blockchain, and of those who had, 80 percent didn’t understand it. So this chapter begins with a blockchain primer—a simplified explanation of what the technology is, what it does, and why it is important.

What is blockchain?

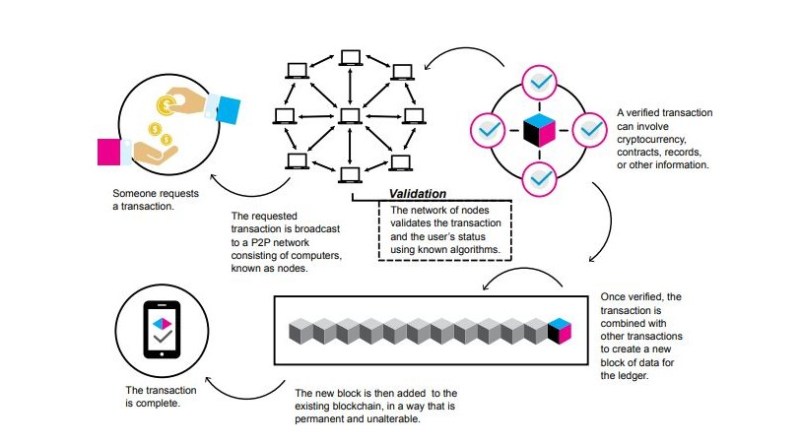

Blockchain technology is a system designed to store digital records of transactions—the transfer of anything (physical or digital) from one person to another. It is often referred to as a digital ledger.

Why is it called blockchain?

Each entry in the ledger is called a block—a piece of data that records what is transferred, from whom, to whom, and when. Sequences of related transactions (transfers of the same stuff to a new person) are linked together in chains that, taken together, record the transaction history. Hence, blockchain.

What does it do?

Blockchain is commonly described as a way of sharing records and data across a distributed, decentralized network, using digital encryption to ensure the data is secure and immutable. Blockchain ledgers are both private and transparent.

Here’s a breakdown of these central terms:

Distributed: Instead of living on one central database, a complete copy of every record in a blockchain is stored on multiple nodes on a network of independent servers (also called peer-to-peer networks). People let their computers function as nodes either because they earn associated blockchain-based currency, or because they want to support a volunteer-based blockchain platform.

Decentralized: Because the data lives on distributed nodes, no single stakeholder controls the network or the data stored on the network.

Secure: This distribution makes the data less vulnerable to damage (malicious or accidental) than it would be in a single, central database. In addition, the ledger uses digital encryption to protect and authenticate the records via large strings of numbers called keys.

Immutable: Once data is written into a blockchain, it can’t be changed. That’s because each record in a blockchain ledger exists on thousands of nodes. If someone tries to edit a record, all the nodes compare notes and arrive at consensus on whether the new data matches the original records. If it doesn’t, the network rejects the change. This makes it difficult (though not theoretically impossible) to retroactively change the information associated with a transaction.

Private: Blockchains may provide anonymity for users. In many blockchains, users complete transactions using a public key and private key pair (a digital ID). It is difficult to match the key to a user’s real-world identity.

Transparent: Even though users can remain anonymous, the ledger itself can be open for anyone to read. Using an appropriate browser, and knowing a user’s public address (which is related to their public key), any member of the public can view the associated transactions. For this reason, blockchain is sometimes described as an open, or public, ledger.

Why is blockchain important?

Whole industries are built on the need for trusted third parties to verify and record transactions: banks for financial transactions, lawyers for contracts, brokers for insurance. Blockchain bypasses these gatekeepers by providing an alternate trustworthy method for verifying transactions. It also provides several advantages over traditional, centralized ledgers. Users can remain anonymous, the records themselves are open to public inspection, and transactions can be recorded and shared in real time.

What is blockchain used for?

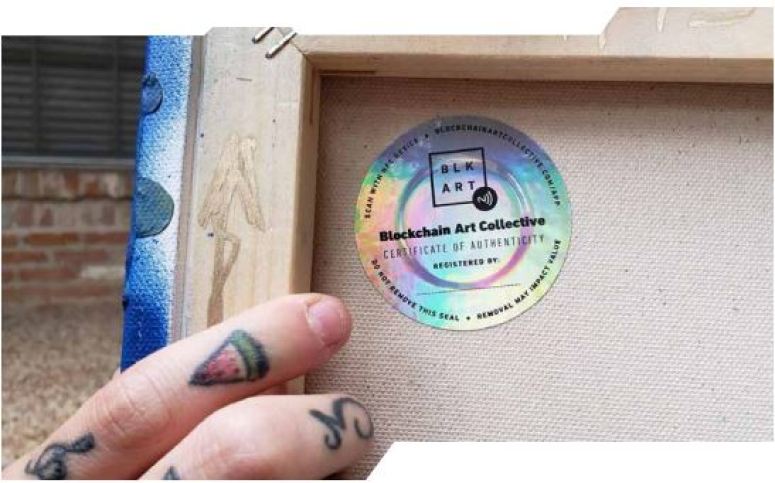

Blockchain can be used to track any kind of transaction—transfer of funds, sales of objects, transportation of goods, and the award of educational credentials, to name a few. With funding from UNICEF, the Amply blockchain platform lets preschool providers track attendance and access state subsidies. The World Food Program recently tested the use of blockchain to track distribution of aid to refugees. Cook County, Chicago, is piloting a blockchain program to track property transfers. The Blockchain Art Collective (BAC) is one of several startups experimenting with the use of blockchain to track the ownership and sale of art. BAC uses an adhesive, tamper-proof seal containing a near-field communication chip to tag works of art. (Near-field communication [NFC] allows phones, tablets, laptops, and other devices to share data with other NFC-equipped devices over very short distances.) The encrypted data on the chips contains information about the work that is also stored on a blockchain. Using an app, users can scan the work with their smartphone to view associated public data.

The most hyped application of blockchain is the creation and exchange of digital “cryptocurrencies” to both create and exchange wealth. People who allow their computers to be used as nodes are rewarded with tokens—cryptocurrencies associated with the particular platform running on that node network. The most widely known currencies are Bitcoin and Ether (the medium of exchange on the Ethereum blockchain platform). Because cryptocurrency supports anonymous transactions, it is sometimes used for illicit purchases on the dark Web, distribution of pornography, extortion, and ransom. It’s distressingly easy to launch a cryptocurrency—almost 2,000 were listed as of fall 2018—and bubbles of experimental cryptocurrencies can make or break fortunes.

But cryptocurrencies are not just about investment, speculation, or hiding illicit transactions. They also can be used to create economies of good. For example, Ben & Jerry’s partnered with the Poseidon Foundation to attach a carbon credit microtransaction to each sale at one of their stores in London. The system showed customers the carbon emissions associated with the production of their scoop of ice cream and gave them the opportunity to buy a carbon credit blockchain token (worth one cent) that goes into a fund supporting forest conservation in Peru. This is one small step towards a global, integrated system of tracking carbon offsets to support implementation of the Paris Agreement on climate.

Finally, let’s take a quick peek at smart contracts—computer programs stored in a blockchain that can automate the unstoppable transfer of payment between users, according to agreed-upon conditions. The execution of these contracts relies on “oracles”—real-time, trusted data feeds that deliver information like weather data, currency exchange rates, airline flight status, and sports statistics. For example, travelers might purchase insurance via a smart contract that pays out when an airport’s database reports that a flight is cancelled. In Museum 2040, one author imagined a future in which artists received micropayments based on museum attendance data (presumably digitally monitored and reported), showing how many people viewed their work currently on exhibit.

Where is blockchain heading?

At this point, it’s not clear which direction this technology will take. On one hand, it is plausible that blockchain could become embedded and ubiquitous. On the other hand, it is equally plausible that blockchain could peak and die. A recent study of 43 blockchain use cases found no evidence that these projects have successfully delivered on their goals, though this finding may simply indicate that the technology is early in its adoption curve. One challenge blockchain will face is the development of functional quantum computers capable of breaking current blockchain encryption. Of course, quantum computing could also be used to generate better codes, setting off a cryptologic arms race or generating other adaptions to the existing system.

blockchain. An embedded near-field communication chip provides a “smart certificate of authenticity.” Photo courtesy of

Nanu Berks.

What This Means for Society

Like artificial intelligence (another huge digital disrupter), blockchain could supplement or supplant traditional jobs in finance, law, real estate, and any other profession that provided high-cost intermediaries to verify transactions. By reducing costs and bureaucracy, blockchains make it cheaper and easier to make payments, register sales of property, and democratize access to legal services.

Blockchain could provide much-needed transparency and security to election systems, potentially supporting the implementation of digital voting, and reducing vote tampering and voter suppression. It can be used to improve the traceability and transparency of agricultural supply systems, facilitating compliance, certification, and the tracking of food contamination. In the cultural sector, blockchain creates new forms of investment and fractionalized ownership around art. For example, in June 2018, the art platform Maecenas held a cryptocurrency auction for digital shares of Andy Warhol’s silkscreen, 14 Small Electric Chairs.

The wholesale application of blockchain to government could revolutionize citizen participation, oversight, and access to state services. Estonia provides proof-of-concept, as that country is using blockchain to improve the data integrity and security of its already robust digital services (known as e-Estonia). Now Estonian citizens can monitor government transactions through a public blockchain.

One of the most promising applications of blockchain technology is the management of personal data—providing what some have dubbed the “self-sovereign ID.” This utopian vision of blockchain sees a future in which everyone has a secure digital identity (in contrast to, for example, notoriously insecure social security numbers) and access to secure, decentralized digital payment systems. In this future, consumers may insist that tech giants like Facebook and Google use smart contracts and micropayments to pay for their use of any individual’s personal data.

Finally, society has to confront the potential environmental costs of blockchain. The original distributed networks and massive calculations that support blockchain are phenomenal energy hogs. Last year, the power needs of Bitcoin alone had a carbon footprint equal to that of 1 million transatlantic flights.

Developers are trying to create greener ways to maintain consensus-based distributed ledgers, but that will require new, less energy-intensive methods of ensuring the security of the records.

What This Means for Museums

Museums are all about keeping secure, immutable records of transactions about collections (aka, provenance). In past centuries, these records were kept in paper ledgers (using archival, acid-free paper, of course), and more recently on in-house databases. The distributed nature of blockchain ledgers could make this data less vulnerable to loss or degradation by neglect. Blockchain could also enable museums to be utterly transparent about collections and provenance, enabling anyone to access data by use of a public key. Blockchain platforms could support secure, transparent, open sharing of provenance data to support claims based on NAGPRA, Nazi-era assets, or repatriation generally. Because blockchain supports secure, global sharing of data, it could play a role in systems like TRUST—the TRansparent User-friendly System of Transfer that helps share biological data in compliance with the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization (ABS) to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Artists are using blockchain to create works that may find their way into museum exhibits and collections. Kevin Abosch created I am a coin, using his own blood to stamp 100 physical works with the blockchain address corresponding to the creation of 10 million virtual works. Primavera de Filippi’s Plantoids are welded, mechanical sculptures that move and grow when people donate bitcoins to pay for the supplies and labor of building them. (De Filippi refers to the sculptures as blockchain-based life forms that are “autonomous, self-sustainable, and capable of reproducing themselves through a combination of blockchain-based code and human interactions.”)

A growing number of artists are using blockchain to tag and track their art. For digital works, the blockchain ID might be coded into the art itself. If this practice becomes common, museums might have to adapt to blockchain record keeping. As Clayton Schuster wrote in an article for the Observer, “[I]magine a future in which a buyer actually wouldn’t trust the authenticity of a work unless it were registered on the blockchain.”

Museums Might Want to…

- Educate the public about blockchain technology, how it will affect their lives, and how they might use it in their work.

- Work with artists and craftspeople to experiment with blockchain tracking of art.

- Consider creating blockchain ledgers for tracking acquisitions, loans, exhibitions, and resources.

- Collaborate with other organizations to create a pan-institutional blockchain for tracking provenance.

Museum Examples

- In 2015, the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts/Contemporary Art announced it had become the first museum to purchase a work of art using Bitcoin. “Event Listeners,” a looping OS X screensaver by Harm van den Dorpel, was itself cryptographically authenticated through blockchain.

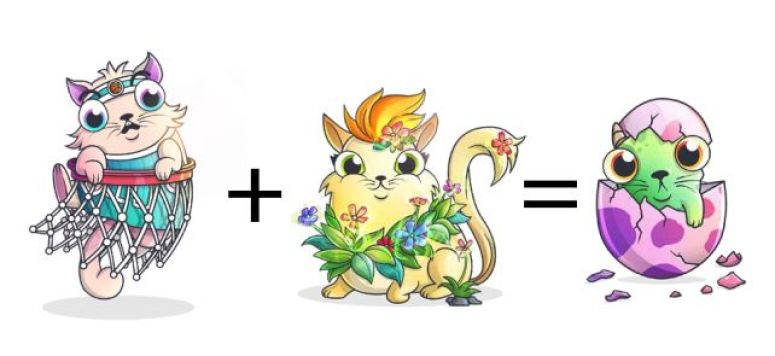

- Several museums have explored blockchain via art. In 2017, the State Central Museum of Contemporary History of Russia in Moscow hosted “CryptoArt,” organized by the Rudanovsky Foundation. Each picture in the exhibition was linked to an open digital VerisArt certificate based on blockchain technology. In 2018, the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany, staged the exhibition “Bringing Blockchain to Life.” The center used CryptoKitties—digital collectables that are bought, sold, and bred on an Etherium blockchain—to explain the inner workings of blockchain to a popular audience.

- In November 2018, the Great Lakes Science Center announced it would accept bitcoin as payment for transactions at its box office. President & CEO Kirsten Ellenbogen characterized the decision as “a small part of the momentum to grow a blockchain ecosystem in Cleveland.” The announcement was timed to coincide with the Blockland Solutions Conference, promoting the creation of a local blockchain technology network.

- In October 2018, Christie’s collaborated with Artory to register art sales. Buyers purchasing works from the collection of Barney Ebesworth were provided with secure, encrypted certification of the sale. (Artory promises that collectors registering works on their blockchain registry will remain anonymous. It’s not quite clear how

that anonymity supports the creation of transparent provenance records going forward.) - Artory is one of several new companies creating blockchain registries to serve the auction market, artists, and private collectors. In 2018, Verisart launched “P8Pass,” developed in partnership with Paddle8, to bring blockchain certification and authentication services to the auction market. Each P8Pass contains detailed provenance information and functions as a unique fingerprint on the Bitcoin blockchain. (Verisart has also launched a hallmark for bronze sculpture called Bronzechain that combines a hallmark stamp with Verisart’s

blockchain.) Codex Protocol provides the Codex Registry—a blockchain-based, decentralized registry for art and collectables that stores ownership and provenance data while providing privacy for auction houses, creators, and collectors.

Further Reading

“Blockchain for Social Impact: Moving Beyond the Hype,” Stanford Graduate School of Business, Center for Social Innovation (2018). This report analyzes 193 organizations, initiatives, and projects that are leveraging blockchain to drive social impact. It includes a blockchain primer and an overview of blockchain applications in a variety of sectors, including democracy and government; energy, climate, and the environment; health; land rights; and philanthropy. Free PDF available at gsb.stanford.edu/sites/gsb/files/publication-pdf/study-blockchain-impact-moving-beyond-hype.pdf.

Artists Re: Thinking the Blockchain, Liverpool University Press (2018). This book features chapters by a diverse array of artists and researchers engaged with blockchain, unpacking, critiquing, and marking its arrival on the cultural landscape for a broad readership across the arts and humanities.