This is one of the five trends from the 2019 TrendsWatch. Click here to read more about the full report.

“Trust is the foundation of society. Where there is no truth, there can be no trust, and where there is no trust, there can be no society.” —Frederick Douglass

In 2016, Oxford Dictionaries selected “post-truth” as the word of the year, defining it as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” The term, coined in 1992, was originally associated with political discourse, but now encompasses a broader shift in how we read, how we learn, and how we talk to each other about the world. When we can’t agree on how to distinguish fact from fiction, we lose faith in experts and institutions. And indeed, trust in government, media, academia, industry, and even nonprofit organizations is at an all-time low. But even as trust declines across the board, nonprofits in general, and museums, in particular, remain among the most trusted sources of information. How can museums retain and build upon this trust? How can they help society reestablish a common framework for telling fact from fiction?

Description of the Trend

Trust depends on our belief that others are telling the truth, so it’s no surprise that trust is suffering in the post-truth world. In 2018, the global Trust Barometer maintained by the marketing and PR firm Edelman registered precipitous drops in the trust granted by the general public to business, media, government, and nonprofit organizations in many countries, including the US. Globally, news media are now the least trusted institutions, creating a feedback loop of ignorance. Half of Edelman respondents reported consuming mainstream news less than once a week, while a quarter read no news at all.

This breakdown in trust may reflect the dark underside of a generally positive trend—the democratization of authority. The rise of the internet and proliferation of social media platforms gave voice to marginalized individuals and groups that were long excluded from traditional authority platforms. Now, Wikipedia, Reddit, countless blogs, and platforms like Twitter and Facebook provide the opportunity for anyone to voice their opinion and share their view of the world. But when anyone can be an authority, how do you assess who really knows what they are talking about? The white, male news anchors of the mid 20th century may have brought a limited perspective to bear on the world, but the fact that everyone listened to what they had to say established a shared starting point for discussion.

The proliferation of information sources has led to fragmentation, as people configure their feeds to create personal echo chambers that reflect their existing points of view. MIT researchers warned of such “cyberbalkanization” back in 1997, predicting that the internet would empower people to form “virtual cliques, insulate themselves from opposing points of view, and reinforce their biases.” We may build these echo chambers without even knowing that we are doing so. Sixty-one percent of millennials report getting their news via social media, and the algorithms that control those feeds aren’t designed to deliver balanced reporting—they are designed to feed people more of what they already like. One pernicious effect of echo chambers is confirmation bias—the tendency to believe that you are right and disregard information that conflicts with your ideas—which makes people less likely to trust sources of conflicting evidence.

Echo chambers also foster the weaponization of news. Once influencers have undermined trust in conflicting sources of information, they can use false information to shape public opinion without fear of being discredited. The latest Trust Barometer survey shows that nearly 70 percent of respondents worry that fake news is being used to manipulate public opinion—and there is growing evidence that they are correct Facebook is the site Americans most commonly use to consume news, and the company recently admitted it has found and deleted nearly 300 fake accounts that were created by a Russian “troll factory” in an effort to manipulate the 2016 presidential election. A university research consortium found that nearly a quarter of Americans visited a fake news site leading up to the election, mostly by clicking through Facebook links. Pew Research reports that the majority of Americans know that the information they get from these platforms is largely inaccurate. However, in what is known as the illusory truth effect, repeated exposure to false information tends to influence what people believe.

And it’s getting harder to distinguish truth from lies as we get better at faking documentation. The manipulation of photographs is, of course, as old as photography itself, but artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms have taken forgery and manipulation of images and audio to a whole new level. Last year, the Canadian tech start-up Lyrebird announced it had used an AI algorithm to create a speech generator that can mimic almost anyone’s voice based on a small sampling of recorded audio. A growing number of sites offer to swap faces in videos to make people appear to be doing something they never did. Combine high-quality fake video and audio and you have deepfakes—highly convincing digital records of people saying and doing things that never actually happened.

We can fight technology with technology, of course. Technologists are developing tools like Claimbuster, which scans digital news stories and speech transcripts and checks them against a database of known facts, and Truth Goggles, which helps readers engage with news articles and evaluate how they themselves process information and draw conclusions. Researchers recently demonstrated a language analysis algorithm that could successfully identify fake news 76 percent of the time—only slightly better than human analysts, but far more scalable. The US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is experimenting with a program called Media Forensics that can detect fake videos.

But as a society we are conflicted about how to apply these fixes: another Pew Research study found that a majority of Americans oppose government regulation designed to combat fake news, preferring instead the freedom to publish and access information—even misinformation. Despite the role for-profit companies have played in enabling the spread of dubious information, the Pew respondents preferred that tech companies self-regulate. (That finding echoes those of the Trust Barometer, which found that people trust industry, especially tech companies, more than they trust their own governments.)

Can trust, once lost, ever be rebuilt, and if so, how? A 2017 study on the rise of fake news by the Pew Research Center and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center found experts were evenly split on whether the information environment would or would not improve. Given the role social media has played in the decline of trust, the future may hinge on how we use choose to regulate, police, and use those platforms.

What This Means for Society

Distrust can lead to polarization. When we can’t agree on how to adjudicate the facts, we have no common basis for discourse. We can’t even agree on the meaning of “fake news”—the term itself has become a shibboleth identifying the political affiliation of the speaker. Some contend that without trust in our political systems, we cannot continue to function as a democratic society—a grave projection. But given the current levels of polarization, how do we begin a nonpartisan effort to fix the system?

Rebuilding trust may turn out to be a multigenerational effort, beginning with significant changes to how we teach children. The “Voice-of-God” narration in traditional textbooks is often used to bury unpleasant issues and avoid controversy. It is more important than ever that we prioritize critical thinking, rather than rote memorization, across all subject areas. Educators are also calling for greater emphasis on digital literacy. Countries may choose to follow the lead of France, which has integrated media and internet literacy into the public school curriculum to teach students how to spot fake news.

A 2018 Knight Foundation/Gallup poll exploring distrust of media found that almost 70 percent of respondents said their trust in media could be restored, in part, by rigorous, transparent fact-checking and lack of bias—though this could be a difficult corrective to apply, as bias, like beauty, is largely in the eyes of the beholder. Blame has been leveled at social media for promoting misinformation, and to meet that charge, social media platforms like Facebook are experimenting with ways to let experts, or readers, flag content for bias or inaccuracy (though research suggests such efforts may backfire).

We can’t blame our rising uncertainty about facts entirely on social media. As we begin to understand how our brains make and store memories, we have learned that we are more likely to remember the stories we have told about remembered events than to remember the original events themselves. It’s now well documented that we can create false memories. Empathetic individuals can even “absorb” the memories of others, remembering their pain as their own. It is healthy for society to confront this fact if only to reduce the incidence of false convictions based on eyewitness testimony. But if we can’t trust ourselves to document the truth, whom can we trust?

What This Means for Museums

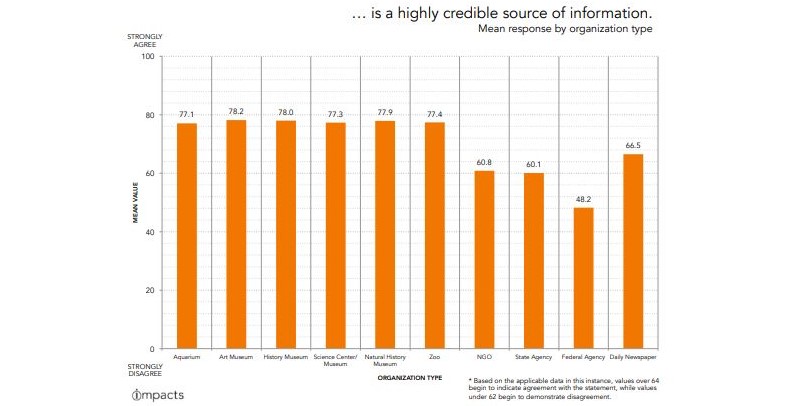

IMPACTS analyst Colleen Dilenschneider refers to museums as having the “superpower of trust.” Analyzing data from the National Attitude, Awareness, and Usage Study, she found that museums of all kinds earn “credible source of information” ratings in the upper 70s, besting other NGOs and newspapers by better than 10 points, and federal agencies by more than 25. In a significant related finding, the US population does not view museums on the whole as having a political agenda.

As Stephen Kehoe points out in the Edelman Trust report, “In a world where facts are under siege, credentialed sources are proving more important than ever.” The trust vacuum, as he dubs it, leaves space for “bona fide experts” to fill. Given the trust that museums enjoy, is there a bigger role they can play as fact checkers? The dark “Fragmentation” scenario in TrendsWatch 2018 envisioned a world in which the original, real things curated by museums become touchstones for the truth, and we see hints that this can really happen. In 2018, some academic historians created widely shared Twitter threads providing context and visual images of primary sources to fact check trending news.

Historically, museums have privileged certain frameworks of knowledge over others—for example, science and academic historical research over traditional knowledge. Opening the museum to nontraditional sources of expertise helps redress historic inequalities in power, while also creating new challenges. People in Western societies are taught to think of truth as a binary state: something is either true (a fact) or not true (a falsehood). Presenting alternative frameworks for seeing the world—such as indigenous knowledge in addition to an archaeological interpretation of history—challenges the museum to help the public understand the nature of these parallel, but potentially conflicting, truths.

Trust confers a power that positions museums to influence the world. But wielding that influence may, paradoxically, erode the public’s trust in museums. The report Public perceptions of—and attitudes to—the purposes of museums in society, commissioned by the UK Museums Association, found that participants regarded museums as trustworthy because they presented balanced, accurate, and objective facts. By contrast, they regarded the media, politicians, and business as biased, politically motivated, and fundamentally untrustworthy. Participants were “very hostile” to the idea of museums being “political, polemical, hectoring, or didactic.” That said, Dilenschneider has also found that the public may respond positively to museums that take a mission-related stand—for example, the Museum of Modern Art highlighting works by artists from Muslim-majority nations in the wake of President Trump’s travel ban. There is a fine line between being principled and being partisan, but museums will need to map that boundary if they are to put people’s trust to good use.

Museums Might Want to…

- Educate the public on museum standards for research. Trust is a precious resource that should not be taken for granted. Be ruthlessly transparent about the source for a statement of fact; make it clear when we are voicing an opinion; admit when we are uncertain; confess when we have been wrong.

- Foster critical thinking. Instead of, or in addition to, presenting a single, definitive narrative, teach visitors how to explore the primary evidence, and invite them to draw, share, and debate their own conclusions.

- Teach people to value evidence-based decision making. This focus will also ensure that policymakers, philanthropic foundations, and individual museum supporters value and support the archives and collections that provide that evidence.

- Acknowledge the role museums have played in perpetuating untruths, whether through unwitting presentation of fakes and forgeries, incorrect catalog data, or uncritical adoption of dominant narratives. Admit that like all experts, museum staff are fallible. Encourage the public to hold us accountable for explaining how we’ve arrived at conclusions, and encourage our visitors to correct us when we are wrong.

- Carefully consider when and how to take a stand on important issues. As trusted institutions, museums have the potential to help reunite our fragmented society and reestablish a common basis for civic debate. However, museums that become perceived as politically partisan may be shunted into the echo chambers of people who already agree with the positions they espouse.

Museum Examples

- The international social media campaign #DayofFacts took place on February 17, 2017, with museums, libraries, archives, cultural institutions, and science centers sharing content using the associated hashtag. Organizers Alli Hartley and Mara Kurlandsky explain that by “simply sharing mission-related, objective, and relevant facts, we aimed to show the world that our institutions are still trusted sources for truth and knowledge.” The Field Museum of Natural History staged a particularly well-received event, captured in a widely viewed video and tagged with the slogan “Facts are always welcome here and so are you.”

- In 2017 and 2018, a number of museums debuted exhibits and programming dedicated to fake news. The Fairfield Museum and History Center in Connecticut presented “Fighting Fake News: How to Help Your Students Outsmart Trolls and Troublemakers,” created for educators as part of CT Humanities’ year-long exploration, “Fake News: Is It Real? Journalism in the Age of Social Media,” and for the Democracy and the Informed Citizen initiative. The Cornell Fine Arts Museum in Winter Park, Florida, mounted “Fake News? Some Artistic Responses,” drawing from the permanent collections to explore how artists have responded to and reacted against the barrage of news, and suggesting that artists are “the fact-checkers of their generations.”

- At the Newseum in Washington, DC, “Digital Disruption” explores how the news industry has been transformed by the internet and digital innovation. The exhibit explores the erosion of local news, the rise of digital news, and the power of Google and Facebook as news purveyors. It also examines fake news, mistrust of the press, President Donald Trump, and Twitter, as well as threats to journalists. With “Fact Finder: Your Foolproof Guide to Media Literacy,” the Newseum education department offers strategies that help students avoid the fakes, hoaxes, and misinformation clogging their newsfeed tools.

- In 2018, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum released a report stating that there was compelling evidence that the Burmese military had committed ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, and genocide against the Rohingya Muslim minority in their country. The museum arrived at this conclusion by consulting with an advisory group of atrocity experts, as well as conducting its own on-the-ground, original research. This investigation was part of the work of the museum’s Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide. This is an example of a museum, impelled by its mission, gathering and weighing evidence and taking a prominent position on a globally important political issue.

Further Reading

The European Association for International Education recommends a framework of eight questions for evaluating the credibility of published research, including: Why was the study undertaken? What is the reputation of the organization and individuals who conducted the research? What were the methodology, sample size, and response rate? And (perhaps most revealing) who paid for the research?

Rachel Botsman, Who Can You Trust?: How Technology Brought Us Together and Why It Might Drive Us Apart,

Public Affairs (2017). Botsman, who teaches at Oxford University, is a widely recognized expert on the economics of trust. In this book, she explores how trust is earned, damaged, lost, and repaired in the digital age.

“This Article Won’t Change Your Mind.” In this 2017 article for The Atlantic, Julie Beck does a good job summarizing “the facts on why facts alone can’t fight false beliefs.” Print and audio versions of this article are available at theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/03/this-article-wont-change-your-mind/519093/.

Crisis In Democracy: Renewing Trust In America, The Aspen Institute and the Knight Foundation (2018). This report by the Knight Commission on Trust, Media and Democracy—a nonpartisan commission of 27 leaders in government, media, business, nonprofits, education, and the arts—examines the collapse in trust in the democratic institutions of the media, journalism, and the information ecosystem, and presents new thinking and solutions around rebuilding trust. Available at http://csreports.aspeninstitute.org/Knight-Commission-TMD/2019/report.