This is one of the five trends from the 2019 TrendsWatch. Click here to read more about the full report.

“Self-care is not selfish. You cannot serve from an empty vessel.” —Eleanor Brownn

Society owes a debt to everyone who does the hard work of making the world a better place: individuals who speak up in the face of injustice, people who band together for collective action, and those who care for others in need. But that work is often exhausting, debilitating, and traumatic. Self-care—taking action to “preserve or improve one’s own health”—has long been practiced by social activists as a way of maintaining their body and souls. In the face of rising stress and stretched resources, it is more important than ever for individuals and institutions to recognize the need for setting aside time and resources for restorative practice.

Description of the Trend

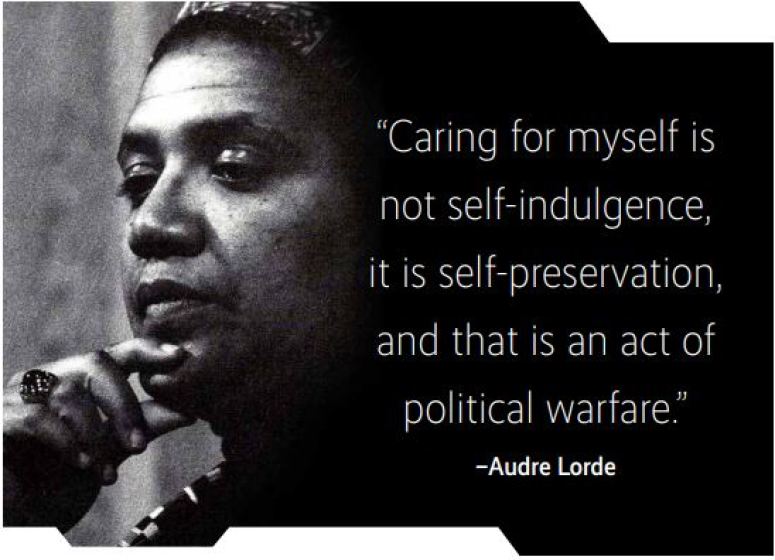

Historically, the disempowerment of marginalized groups, such as enslaved people and women, was justified by the argument that they were unable to care for themselves. In the 20th century, antipoverty activists flipped this reasoning, affirming that having the capacity to care for oneself is a fundamental human right. Health professionals, seeking to elevate public wellbeing, began to preach the value of self-care as a complement to the limited medical care available to many poor, rural, or disadvantaged communities. In the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, feminists, people of color, and LGBTQ activists adopted self-care as a means of affirming their value as individuals and sustaining their work. By the 1980s, the term had become co-opted and commodified, turned into a marketing slogan for lifestyle products and services. However, in the past few years, we have seen the resurgence of self-care as a political act, affirming the self-worth of marginalized people and fostering the physical and psychological resilience they need to assert their rights.

To the extent that self-care arose as a strategy to cope with unequally distributed resources for wellbeing, the need for self-care can be seen as a measure of social equity. Communities disadvantaged by their race, gender, class, or sexual orientation are particularly vulnerable due to the health risks associated with their status and their lack of access to publicly supported resources for care. With respect to African American communities, this double jeopardy has its own name—“John Henryism”—that refers to the negative health effects associated with the extraordinary level of effort needed to overcome racism and bias.

The need for relief is not confined to specific communities. The American Psychiatric Association’s 2018 report revealed high levels of anxiety among the general public, with 39 percent of respondents saying they are “more anxious than last year.” Technology plays a role in this rising baseline as cell phones, the internet, and social media have created the expectation to be on call 24 hours a day. We are just beginning to measure the psychological cost of this hyperconnectivity. Social stress has increased as well, with the global rise of nationalism, nativism, and anti-immigrant sentiment. In the US, hate crimes—a leading indicator of social stress—have risen for the past four years, and spiked in the two weeks following the 2016 presidential election.

In a capitalist economy, any need is going to generate a corresponding business, so it is unsurprising that there is an $11 billion industry marketing self-care products and services. On Twitter, the tag #selfcare is as likely to be attached to sponsored promotions for papaya facial treatments and mink eyelash extensions as to posts about mental health and social activism. For this reason, self-care is sometimes dismissed as trivial and self-indulgent, despite its long history as an important tool for people fighting social injustice.

It can also be difficult to talk about self-care because it takes so many different forms. For people with chronic illness, it can be a way to manage their own health. For people working in high-stress, front-line jobs as first responders or emergency care medical staff, it can be a way to cope with the fallout from exposure to traumatic experiences. For the general public, it has become broadly synonymous with personal wellness and healthy living. In practice, it can include attention to nutrition, exercise, socializing with friends and family, spiritual practice, and recreation, as well as many other ways to care for mind and body. There is no one-size-fits-all prescription. Introverts may require significant alone time to rebuild their emotional energy, while extroverts recharge by spending time with friends. For some people, physical wellbeing may hinge on keeping fit, for others controlling their diet. For at least a third of us, it may include getting more sleep. Some people may need a “digital detox” to recover from the stress of hyperconnection, while members of marginalized groups may turn to social media to access community and support.

What This Means for Society

As a whole, the US is not a culture that recognizes and supports the need for individuals to care for their own wellbeing. The difficulty may be embedded in our national DNA—a Protestant heritage of personal responsibility and belief in self-reliance. This legacy has given rise to a work culture in which employees demonstrate their value through self-sacrifice, and working long hours is a marker of success.

Yet the culture of hard work and self-reliance has created significant costs to society. In the workplace, stress leads to absenteeism, disengagement, decreased productivity, burnout, and high turnover. Research shows that 36 percent of workers in the US suffer from work-related stress, and the overall costs—in lost work days, health effects, and decreased performance—are as high as $300 billion a year. The chronic stress of caregiving work can lead to compassion fatigue, characterized by apathy, isolation, and secondary traumatic stress disorder triggered by treating those who are traumatized. In response, some high-stress caregiving professions are incorporating self-care into training curriculums and work environments. There is a growing body of evidence that such practices work. For example, fostering healthy lifestyles, mindfulness and meditation, and reflective writing has been shown to reduce the likelihood of stress and burnout among physicians caring for terminally ill cancer patients.

Residents of the US are further stressed by the lack of a comprehensive support system for the basics of life, such as health care, paid sick time, and parental leave. In the absence of programs provided or mandated by the government, what are the responsibilities of employers? The data on stress and productivity suggest an economic argument for supporting workers’ efforts to care for themselves since the space, time, and resources to support self-care can be relatively affordable employment benefits. On the other hand, there is a risk that such workplace perks might substitute for deeper, more meaningful change such as paying higher salaries or providing better health coverage.

Stress and its costs are unequally distributed, disproportionately affecting racial and ethnic minorities and populations with low socioeconomic status. In the face of rising inequality, self-care is an important corrective to the health effects of the effort required to overcome social and economic barriers. The commodification of self-care is therefore particularly pernicious. Could wellbeing become yet another luxury only accessible to those with the time and money to care for themselves?

If self-care is seen only as an individual responsibility, there is a danger that it will become yet another a source of stress—a guilt-inducing item on the checklist of things we think we ought to do. We need to be careful that we do not use successful self-care as an excuse to avoid changing the systems that cause harm. Just as the need for self-care is driven by stress created by our organizational and social systems, the most effective solutions will themselves be systematic. Systems that support self-care must respect the myriad forms that support can take.

identity, and social injustice.

What This Means for Museums

Research by Tech Impact shows that nonprofit workers often feel overworked and that their productivity drops when the workweek reaches 50 hours or more. Post-recession, it has been increasingly difficult to fund nonprofit work, and organizations tend to pass this pain on to staff in the form of low pay, long hours, and high expectations in preference to cutting services to the communities they serve. While nonprofit workers often are motivated by a commitment to mission, this dedication comes at a cost. A 2011 study by Opportunity Knocks suggested that as much as 30 percent of the nonprofit workforce was experiencing burnout, and another 20 percent was at risk.

Museums, along with other employers, pay a high if hidden price for stress. Turnover results in a loss of knowledge, experience, and institutional memory. It necessitates recruitment, hiring, and training, as well as incurring the hidden costs of work that goes undone while a vacancy is unfilled. Despite this, museums often cannot afford (or feel they cannot afford) many of the perks that successful for-profit companies can offer to employees. Focusing on employee care can include a number of low or no-cost practices, such as offering flexible work schedules or designating a workplace “de-stress” room, that have a significant impact on employee wellbeing. Yet it is more common for museums to create self-care and wellness programs for the public than for their own staff.

For museums that do want to focus on employee wellbeing, the solution is not as simple as offering a menu of yoga and meditation classes. Laszlo Bock, former senior vice president of people operations at Google, maintains that one of the most powerful guiding principles a company can adopt is “make life easier for employees.” That means being attentive to and flexible about individual needs. Some organizations let employees telecommute, condense their workweek, customize their work hours, negotiate job sharing, and donate sick time to colleagues. Other “family-friendly” work practices include providing a dedicated, private space for new mothers to pump milk, accommodating parents who need to bring a child to work on occasion, and offering paid parental leave. Rather than obsessing about applying one set of policies “fairly” across the board, many organizational experts recommend focusing on what an individual needs to get done, and what support they need in order to be able to do a good job.

Museums Might Want to…

- Start by talking to employees about the specific conditions that drive stress in their jobs, such as harmful or unsafe conditions, understaffing, irregular hours, overwork, expanded responsibilities due to downsizing, inadequate equipment or materials, or a lack of regular, clear feedback from their supervisors.

- Implement Bock’s approach towards “making life easier for employees.” Review policies for pain points and identify practices such as telecommuting and flex time that employees can use to meet their individual needs. Design employment and workplace policies to be supportive rather than punitive.

- Create an annual “quality of life” survey to benchmark progress in lowering employee stress and providing a supportive work environment, and identify potential actions. But only conduct a survey like this if you are ready to act on the information it provides. Otherwise, you may add to people’s stress and frustration.

- Create a staff committee to foster self-care in the organization, and give participants the resources and authority to implement their ideas. Ensure that staff can access resulting programs during officially sanctioned work time, without adding to their own workloads.

- Set a positive example, starting with the director/CEO and the organization’s leadership staff. Encourage management staff to be open about their own need to care for themselves, share best practices, and model work-life balance. Train managers to include self-care in their discussions with the people they supervise. Encourage staff to take sick time when they need to, and to use their vacation days, even if this means redistributing assignments or adjusting deadlines.

- Build support for these policies with the board of trustees. Make the “business” case for self-care by documenting tangible organizational benefits such as higher employee engagement, increased productivity, and lower turnover.

- Offer self-care programs for the community, with an emphasis on serving populations that may have particularly acute needs and face barriers to safely accessing existing options.

“Reclaiming Our Time: Radical Self Care Now!” at the California African American Museum. Photo by HRDWRKER.

Museum Examples

- The Museum of Science in Boston is in its ninth year of an employee wellness program that offers programming in physical, emotional, financial, and social health. This initiative has included a month-long yoga course, a six-week tai chi series taught by a museum employee, a virtual summer race series, a mobile mini-golf tournament, healthy chef demonstrations from catering partner Wolfgang Puck, a staff-created cookbook of healthy recipes, and annual financial planning sessions. On a quarterly basis, the wellness program offers “quiet time” sessions in the museum’s Charles Hayden Planetarium, providing staff

with a break from the regular workday via tours of outer space accompanied by calming music.

- The California African American Museum’s program “Reclaiming Our Time: Radical Self Care Now!” explored “how a balanced and vibrant life demands that we take our needs into consideration and act upon them.” The series included tai chi chuan classes, coffee tasting, and a panel of “diverse and fearless leaders sharing their methodologies for care while making a major impact in their respective fields.”

- From September 15, 2018, to January 6, 2019, “Group Therapy” at the Frye Art Museum in

Seattle featured a roster of international artists addressing themes of healing and self-care through a range of media. During the exhibit, the museum also functioned as a community “free clinic” with immersive installations and participatory

projects. By including racism, sexism, and political tribalism as social pathologies, the show reframed what it means to be ill in the 21st century and offered community building as one possible curative. - In July 2018, the Nantwich Museum (UK) became the first museum to be recognized by the National Health Service with a Bronze Self Care Award for their work in sharing key health and wellbeing messages with their

staff, volunteers, and visitors.

Further Reading

Seema Rao, Objective Lessons: Self-Care for Museum Workers, Amazon Digital Services (2017). This workbook presents 50 exercises to help readers explore their own strengths as well as their feelings about

working in the museum sector.

Beth Kanter and Aliza Sherman, The Happy, Healthy Nonprofit: Strategies for Impact Without Burnout, Wiley (2016). This book offers strategies for organizational leaders who want to avoid nonprofit burnout among their staff. The authors propose a system they call “We-Care,” in which “employee wellbeing takes a front seat next to organizational performance.”

wow nice article