This article originally appeared in the July/August 2019 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

Traditional museum models of interpretation have historically failed Indigenous people by creating static spaces where the “vanishing Indian” exists only in the past. This presentation casts Native peoples as unreal, and sometimes mystical, for museum-goers. This misrepresentation, when not recognized and addressed, forms harmful perceptions and oppresses Indigenous people.

The Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, Maine, regularly considers and confronts this problem. Our museum spaces are constructed, supported, and informed by a decolonizing framework that offers a new and welcome perspective for museum workers and visitors alike.

Our decolonizing framework is informed by the research of Ho-Chunk scholar Amy Lonetree. Using organizational examples and rigorous historical research, Lonetree contends that decolonizing practice is evident when museums collaborate with Indigenous people, privilege Indigenous perspective and voice, and commit to truth-telling history and revealing its harmful legacies. The Abbe applies this framework organization-wide, in its operations, projects, exhibits, educational programming, governance, planning, advocacy, and more. This results in a process—a way of working—rather than an artificial, decolonized product.

Decolonization as an end goal is not possible because of the sustained impact of colonization, which has reshaped present-day lifeways, experiences, and relationships for Indigenous people. The United States remains a colonizing presence and force on Indigenous lands with no plans to retreat. Therefore, it’s important for museums to understand that they can engage in decolonizing practice, but decolonization will not be an end result.

In addition to Lonetree’s research, much has been written about why decolonizing practice is needed and overdue, and some has been written about how to do the work. Little has been written about how visitors react to and experience a decolonizing museum. Here, we share some of what we’ve observed and learned over the seven years of decolonizing practice at theAbbe Museum.

What We’ve Done

Even before we began our decolonizing efforts, we knew that Abbe visitors were ready to engage with decolonizing content, such as hearing directly from Indigenous people about their world view and learning difficult history. A 2012 Visitors Count! survey administered through the American Association for State and Local History revealed that the majority of our visitors expect to be uncomfortable because the Abbe is focused on Native history. (Our survey benchmark group included museums focused on social justice and sites of memory and remembrance.) Visitors also indicated that this discomfort is acceptable, and they’re willing to engage in it.

There was, and continues to be, an understanding that there is value in learning the full measure of history, even when the topics are painful. Survey respondents also said that they found the Abbe to be “one of the few places where it is conducive to learn about, discuss, and explore difficult issues in history.” This knowledge supported the board and staff’s decision to create a decolonization initiative and a new core exhibition, “People of the First Light,” which informs interpretive programs and other exhibitions.

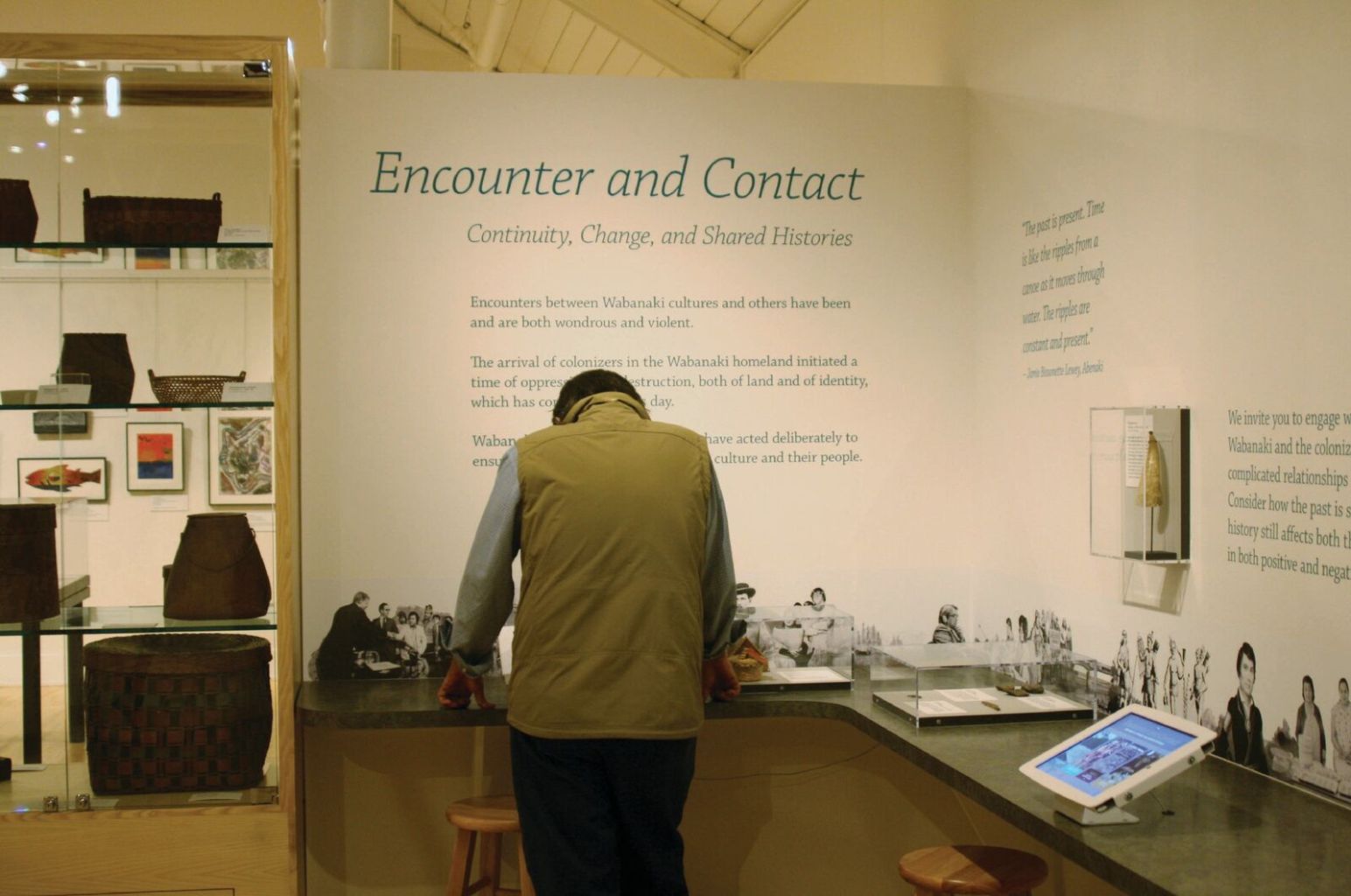

Part of our strategy is a willingness to prepare our audiences by being forthright about our decolonizing efforts. In the Abbe’s orientation gallery, just inside the museum’s main entrance, we explain our decolonizing practice, define sovereignty, and introduce the Wabanaki Nations of Maine, northern New England, New Brunswick, and the Canadian Maritimes. To keep the museum-goer engaged, we have trained the visitor services staff to respond to the inevitable difficult questions that visitors unfamiliar with decolonization, or even cultural sensitivity, might ask, such as “Isn’t it about time that we got over all the bad blood? We need to focus on the good.” Or, “Those pictures (in exhibits) don’t look like Indians; they look European. They probably aren’t real Indians anymore.”

As a non-tribal museum interpreting Indigenous topics, history, and art, it is essential that we consider how our educational and visitor services staff understand the ethics and techniques of this work. When training new staff, we spend a lot of time preparing them to engage with visitors and to nurture respectful dialogue about Wabanaki peoples and lived experiences. All incoming staff engage in racial bias training; are exposed to numerous training opportunities each month; and learn the techniques of facilitated dialogue, which engages participants in thinking and discussion that reveals personal relevance and affirmation while being clear about boundaries and dismantling racist systems and behaviors.

In addition, the Abbe works with 30 Indigenous educators, performers, artists, and demonstrators to deliver educational programming. We feature the artistic works of approximately 80 Indigenous artists in our gift shop. Staff members have multiple opportunities to build relationships with tribal community members. They understand the importance of representation and self-determination and how that is marginalized in white supremacist structures. As an institution, we actively work to dismantle systemic racism—top down, bottom up, and across teams. Within this workplace culture of inclusion, decolonizing thinking and process lead to growth and change. Our ultimate goal is to present a dignified, humanizing view of Indigenous culture and history.

Decolonizing methodology is visible beyond the entrance and throughout the Abbe. We create educational opportunities in all of our gallery spaces, and we regularly consider how we frame our public programming.

For instance, if a program is related to material culture, we contextualize it by emphasizing humanistic relationships. How is an item an example of Wabanaki technology? How does this particular object tell the story of thousands of generations of Wabanaki people living in the homeland? Instead of focusing purely on the object itself, we want to focus on the personal experience of Wabanaki peoples. Ultimately, we’re communicating to our educators and our audiences that people are more important than objects. Though it may contradict traditional models of museum work, we hold fast to this truth.

Visitors reach deeper levels of understanding when exhibits are presented within a decolonizing framework. By talking about our process, we help visitors become critical museum-goers, ready to question narratives and displays. Instead of focusing on material culture and static narratives, visitors are reminded that museums can be transformative spaces where truth, identity, and self-determination are the priority.

How Have Visitors Responded?

Responses from our audiences consistently reinforce both the strength and necessity of decolonizing our museum’s content delivery systems. The Abbe’s education team has embedded several touchpoints for visitor feedback throughout the museum. Whenever possible, these interactives are dialogic, intended to promote conversation.

One example is in the Circle of the Four Directions—a contemplative space designed for reflection and minimal visual stimuli—where visitors can respond to questions in a series of dialogue books. Each book asks a specific question, such as, “Should a museum like the Abbe work to engage people in taking action on issues important to the Wabanaki? How can a museum or other educational organization do this?”

The responses are evocative, emotional, and reiterate why this work is essential. For example, one visitor shared, “The Abbe should be involved in inclusive curriculum building. The teaching of American history needs to cover all aspects—the negative impacts of colonization, slavery, Jim Crow, anti-immigrant sentiments—so that we can all be more knowledgeable and hopefully do a better job of making life in the future better for all people—especially those who have been hurt.”

The themes reflected in the dialogue books are supported by the messages in our guestbooks, digital reviews, and the conversations happening between visitor services staff and visitors. Abbe visitors continue to reiterate that decolonizing is not only important but a key factor in their enjoyment of our museum.

Advice for Other Museums

We often receive inquiries from other institutions about how they can incorporate decolonizing practices within their museums. Our response is that there is no prescriptive way to engage in decolonizing work, nor a procedure for specifically applying it to museum education. We have found that being prescriptive and formulaic is oppressive and contrary to educational pedagogy that is collaborative with Wabanaki people, prioritizes Indigenous voice, and is wedded to truth-telling.

Museums looking to do decolonizing work must analyze their own needs and priorities, learn their histories as a museum, and understand the past and present relationships between Indigenous people and the museum. Doing these things will reveal a story that will vary from museum to museum; this story must be understood and unpacked for the decolonizing practice to take root and be effective.

The examples offered throughout this article are admittedly anecdotal and more qualitative than quantitative. This is often the case with social change. Over the past few years we’ve regularly conducted visitor and teacher surveys that indicate audience interest and engagement, but a deeper, more thorough look at our decolonizing museum practices is warranted.

With the help of an Institute for Museum Library Services grant award in 2018, the Abbe has been seeking to answer the following questions: What is the methodology of this work and where is the community of practice? How do we do this and who are we learning from and with? In addition, grant funding is supporting the creation of the Museum Decolonization Institute (MuseDI), housed at the Abbe, which will train museum workers on how to initiate decolonizing museum practices and what they could look like in their home museums. In the process, we’ll evaluate our effectiveness as a decolonizing museum by looking at our practices, policies, and protocols to date.

Audiences are ready to engage with a decolonizing framework and museum environment. It’s now our duty as contemporary museum workers to provide this.

Evidence of Decolonizing Practice

As documented and inspired by Ho-Chunk scholar Amy Lonetree

Collaborate with tribal communities. When an idea for a project or initiative is first conceived, we have a conversation with Native advisors to make sure it’s a story or activity that we have the right to share or pursue. We don’t get halfway down the planning timeline and then check with Native advisors about how we’re doing and if we’re getting it right. Native collaboration needs to be at the beginning and threaded throughout the life of the project.

Privilege Indigenous perspective and voice. The vast writings on the human experience are with little exception written by white academics and observers. When we begin to prioritize the writings and observations of Indigenous scholars and informants, the story broadens, expands, shifts, and brings a clearer and non-oppressed perspective of Native history and culture.

Be in the business of truth-telling. Histories of Indigenous people connect to today’s challenges. Issues around water quality, hunting and fishing rights, and mascots are connected to the past and the present. When we present this full history, we have a better opportunity to identify harmful statements and practices.

Resources

Amy Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and TribalMuseums, 2012.

Jamie Bissonette Lewey, Cinnamon Catlin-Legutko, and Suzanne Greenlaw, “Process Not Product: Decolonizing Practice at the Abbe Museum,” under peer review for publication in Curator: The Museum JournalCaption 25Modern-day regalia and historic images together tell the full story of Wabanaki people in the homeland. Caption 26The Abbe Museum operates from two locations in Bar Harbor, Maine. The downtown BarHarbor location opened in 2001 and operates year-round.

Wabanaki advisors and four Wabanaki artists inspired and fueled the entire exhibition process and had final say over the text, interactives, and objects.

Great issue! I am particularly eager to see this museum.