The act of understanding is fundamental to the museum experience. In visiting a museum, we come to understand the objects placed before us, along with the stories of their human pasts. So too is understanding a key to creating these experiences for audiences. Exhibition planners must understand the audiences they try to engage: What background knowledge do they bring to the objects? What are their cultural perspectives? What are their emotional sensitivities? The creators of museum experiences need to be knowledgeable not only about the stories they tell, but also about those to whom they tell them.

In 2016, the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM)— a museum of art, culture, and creative expression located in Salem, MA—established a Neuroscience Initiative, by virtue of a generous grant from the Boston-based Barr Foundation. The museum’s goal was to use neuroscientific research to understand its visitors in new ways, and then to design art experiences in PEM’s galleries accordingly. I came on board as the Neuroscience Researcher in 2017 to help enact this program. I now spend my days investigating the dynamics underpinning the aesthetic, emotional, intellectual, and social engagement that comprises the museum experience.

In this post, I will share how our research has helped us understand our visitors in new and unexpected ways. But first, let’s explore how experiences—including museum experiences—are generated on a (neuro)biological level.

The Origin of Experience: The brain

Experiences arise when we are stimulated by an object or phenomenon external to our bodies. Our sensory processing systems take in these external stimuli and allow us to interact with them and internalize their properties. All five of our sensory organs (eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and skin) feed information about environmental stimuli into our central nervous system, which is comprised of our brain and spinal cord (Figure 1A).

Once it arrives in the brain, that sensory information moves through networks involving many different neural regions. Some of the neural signals act within the brain to give rise to phenomena such as cognition, emotion, and memory (Figure 1B). Others travel down the spinal cord and into the body to influence our physiology (Figure 1C), various glands, and the skeletal muscle that controls behavior (Figure 1D), including the eye muscles that determine where we look.

In short, what we experience is a product of the brain, and thus our ability to assess the nature of an experience depends on our ability to understand and measure the functions of the brain. But traditional museum evaluation techniques, like visitor self-report and observation, cannot accomplish this on their own. While they probe certain conscious and observable aspects of the visitor experience, they omit other aspects of the emotional experience (see Box 1) as well as more nuanced behaviors unobservable from a gallery corner, such as the eye movements viewers use to engage with works of art. To access these brain-derived aspects of an experience, we must employ other metrics, like the biometrics and mobile eye-tracking technology the Peabody Essex Museum used to analyze how visitors interact with wall text.

A Case Study: Artist wall quotes as interpretive device

Like many museums, PEM employs a wide range of interpretive devices to help visitors understand and connect with the art on view. One such device is the incorporation of artist quotes into the exhibition text, whether contextualized within an object label or as print on the gallery walls. The PEM exhibition Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings, shown in the museum in the Autumn of 2018, employed both approaches. During the run of the show, we performed a study to assess the utility and impact of eight wall quotes (Figure 2) on the visitor experience.

Our hypothesis was that reading Mann’s quotes would enhance visitors’ engagement with her photographs, including the emotional tenor and duration of their responses. To investigate this, we recruited twenty-four participants—none of whom knew the purpose of the study—via social media to view the exhibition wearing mobile gaze-tracking glasses, which captured their fields of vision, and wireless galvanic skin response (GSR) sensors, which continuously measured their levels of emotional arousal. Afterward, they completed an exit survey about their conscious emotional and cognitive responses, including their use of and reaction to the artist wall quotes.

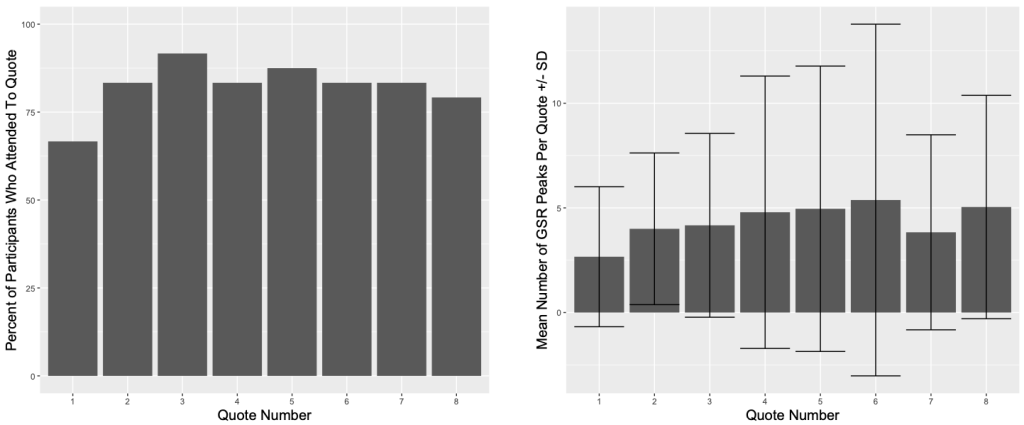

In the results, all three of our metrics suggested that participants did attend to (and presumably read) the artist wall quotes, with some participants generating emotional responses to the quotes as well. On the exit survey, twenty-three of twenty-four participants reported noticing the quotes; twenty-two reported reading them; and twelve reported responding to them. Corroborating these results, the gaze-tracking data showed that well over 50 percent of participants spent time attending to each of the eight quotes distributed throughout the exhibition (Figure 3, left). Furthermore, the GSR measurements showed that the different quotes elicited variable levels of emotional arousal (Figure 3, right).

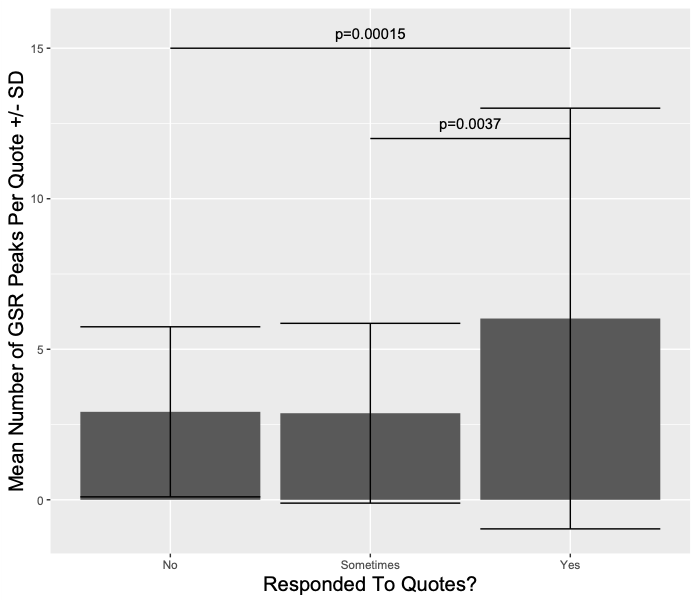

We also found that our GSR-based measure of emotional engagement aligned with the self-reported data. Participants who reported responding to the quotes demonstrated a statistically significant higher GSR response to the quotes than those who reported that they responded to the quotes sometimes or not at all (Figure 4).

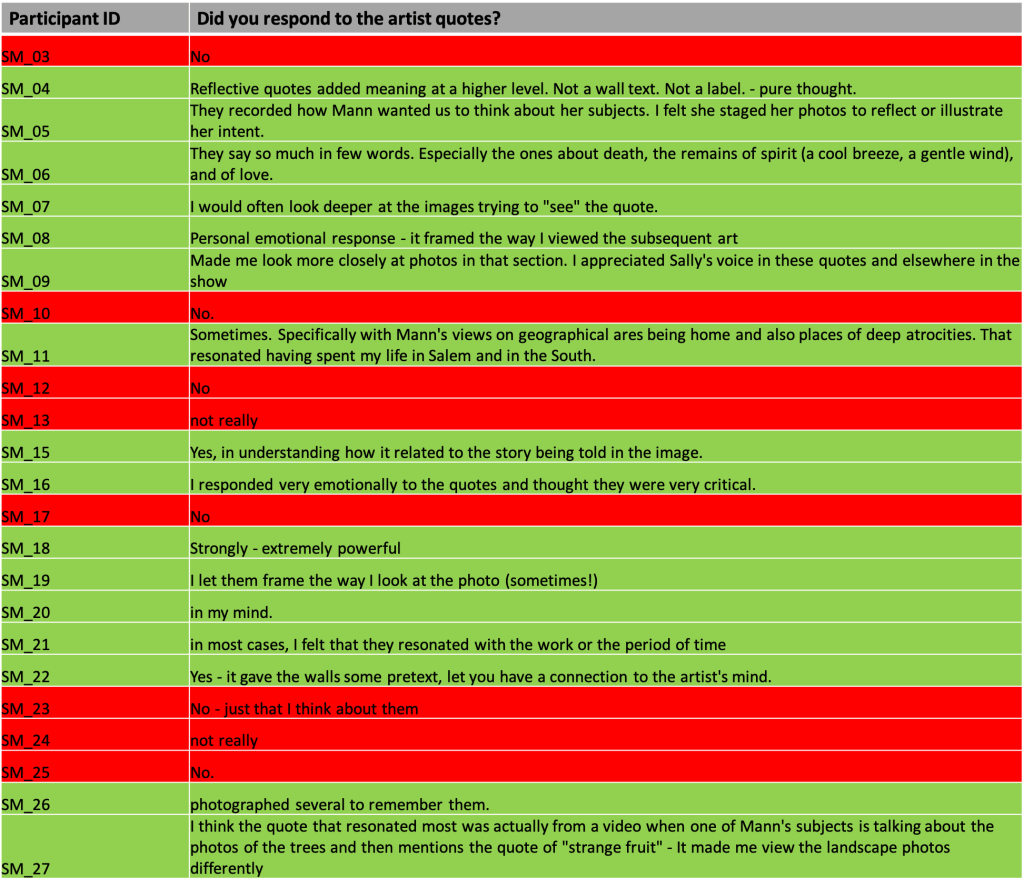

These results suggested that the wall quotes were successful in enhancing visitor engagement within the exhibition, but we still did not know whether the quotes impacted emotional engagement with the surrounding photographs. While participants often indicated that the quotes did add to the experience of viewing the artwork (Figure 5), it remained unclear whether this impacted their level of emotional arousal, as measured by GSR. If it did, we would expect that the GSR response to a photograph immediately following a quote would be higher than the response to a photograph immediately preceding a quote.

Although there was a trend toward a higher GSR response to post-quote photos relative to pre-quote photos, this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 6, compare pink and blue bars), which suggests that the quotes may not have facilitated a more emotionally aroused response to the subsequent photographs. Moreover, participants who reported having a response to the quotes did not demonstrate a significantly larger difference between pre- and post-quote photograph GSR responses relative to the participants who reported not having a response to the quotes (Figure 6). This suggests that, even for those participants who had conscious responses to quotes, the quotes did not elicit higher levels of emotional arousal in response to the surrounding artwork. A replication of this study with a larger sample size would help to answer this question definitively.

Implications for exhibition design

Even if the quotes did not seem to impact the level of emotional arousal in response to the displayed artwork, the self-reported comments suggest they may have enhanced other aspects of the viewing experience, such as intellectual insight and the emotional valence (pleasantness) of the viewing experience.

But does it matter that the quotes failed to enhance levels of emotional arousal in response to the photographs? As I mentioned previously, experiences high in emotional arousal are more likely to be imprinted into memory. It would be interesting to administer a second survey months after the exhibition, querying the participants’ memories of the quotes and the works of art associated with them. Would the participants who demonstrated higher GSR responses actually remember the quotes and artwork better than those with a lower response? Given the literature linking elevated levels of arousal with enhanced memory formation (Anderson, Wais, & Gabrieli, 2006; Kensinger, 2009), I would hypothesize that they would.

Thus, the important question may not be whether to use wall quotes in an exhibition, but rather how to use them. The data presented here suggest that artist wall quotes elicit attention and emotional responses from visitors that, in some cases, may carry over onto the artwork amongst which they are situated. However, whether or not these experiences will carry on in the memory of the visitor is as of yet unknown.

Take-home message

Incorporating multiple metrics into your evaluative strategy allows for a nuanced understanding of how museum-goers experience exhibitions. In our study, assessing emotional engagement through both biometric and self-report methods facilitated the understanding that artist wall quotes impact the visitor experience, largely in positive ways.

This mixed-methods approach to assessing visitor experience also enables museum evaluators to ask many questions of the same dataset; the results presented in this blog are but a fraction of the findings yielded by the study. The upfront cost of investing in the various technologies required to execute this evaluative strategy may be outweighed by the long-term ability to dissect the visitor experience along multiple axes (cognitive, emotional, behavioral, etc).

In using a combination of tools to monitor many different manifestations of brain function, we can analyze the impact and efficacy of specific interpretive and design elements within exhibitions, to understand our audiences on a new level. Investing in resources that foster this understanding may enable museums to create more meaningful experiences for our visitors.

Try it at your museum! We recognize that not every museum has the resources or desire to invest in biometric technology. Nevertheless, we think that there are some transferrable elements of our approach that do not pertain to hardware. The scientific process is the fundamental underpinning of our approach. Below are some key steps in this process that you might be able to implement in evaluative studies at your own museum.

Key elements of a scientific approach:

- Pose an experimental question that you’d like to address.

- Do some background research in the published literature to find out what’s already known about your question.

- Develop and articulate a testable hypothesis about how you expect a particular design or interpretive element to impact the visitor experience.

- Create a rubric of potential outcomes. How will you know if your hypothesis is supported? What forms will the supporting evidence take?

- Test your hypothesis in a visitor study.

- Once you’ve analyzed your data and drawn some conclusions, work to develop a process within your institution for sharing and acting on your research findings.

Acknowledgments

We’d like to offer our sincere thanks to all the volunteers who participated in this study; we couldn’t have done it without you! We’d also like to acknowledge Shimmer Inc, our collaborators on this study, who provided priceless consultation on study design and analysis. Finally, we’d like to thank the PEM Guest Experience staff for facilitating the complicated logistics associated with this study.

References

Anderson, A. K., Wais, P. E., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2006). Emotion enhances remembrance of neutral events past. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(5), 1599–1604. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506308103

Kensinger, E. A. (2009). Remembering the Details: Effects of Emotion. Emotion Review, 1(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073908100432