Dennis O’Toole has held leadership roles in museums throughout his career, as well as been a prominent force in the American Association for State and Local History. His column below is the first in a series of blogs I am calling, “You’re Doing What?!” His and other similar pieces will serve as inspiring stories about what colleagues and compatriots in the arts are doing during so-called “retirement.” These blogs will highlight sterling examples of ‘creative agers’ who have combined their passions and experiences in ways that continue to benefit the greater whole.

–Bill Tramposch, Aroha Fellow for Museums and Creative Aging

I didn’t think of it as retirement. I liked to call it semi-retirement; saying goodbye to the nine-to-five history museum world and moving with my wife, Trudy, across the country to a small ranch, Monticello Box Ranch, in the outback of southern New Mexico. It was an unplanned, serendipitous, even impulsive change in our life that raised eyebrows amongst our children and evoked puzzlement from friends and colleagues.

“Where are you going?” people would ask. To a small ranch thirty-five miles up a canyon from Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, we’d answer. It’s off the power grid, our nearest neighbor is eight miles away, we’ll pump our own water, and we’ll be our own fire department and police department. Oh, and the creek occasionally becomes a raging, flooding river during the summer monsoon season, cutting the ranch off from the rest of the world.

“And what do you plan to do on this ranch?” would be the next question. Archaeology, was our glib response. Excavations. Though I had worked with archaeologists during my history museum career (at Colonial Williamsburg and at Strawbery Banke Museum), I wasn’t of that profession. I am a historian and public history educator, another tribe altogether. And we would now be on our own, without an established organization to support us, in the high-desert wilderness of New Mexico with the nearest community, the tiny (fifty-person) village of Monticello, forty-five minutes downstream.

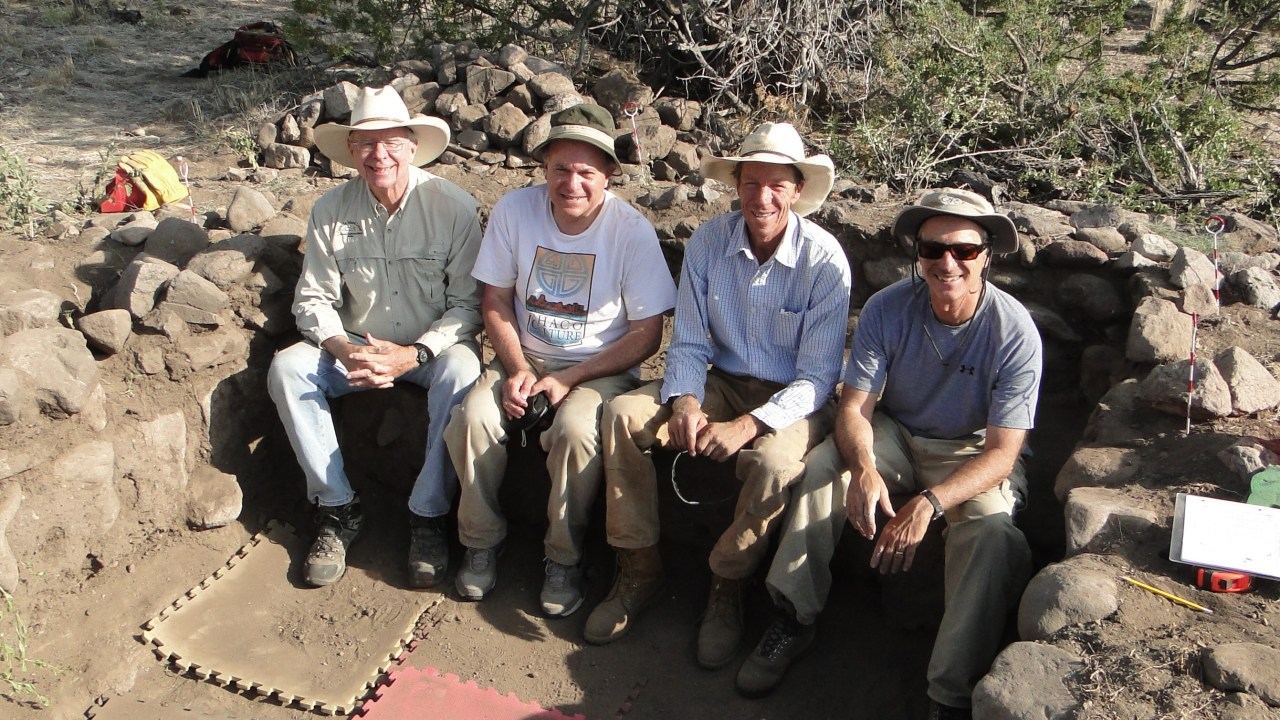

So, our first steps were to create a non-profit entity: the Cañada Alamosa Institute, find an experienced ranch manager, and contact a seasoned archaeologist of the American Southwest, Karl Laumbach, and ask him to provide the intellectual and field leadership we needed. (With his friend and fellow archaeologist Steve Lekson, Karl had conducted an ethnological survey of the canyon in the early ‘90s, so he was tailor-made for our project.) Luckily, he said yes. Together we crafted a research design with goals and a plan to achieve them. Then, through Karl’s connections, we enlisted students from the archaeology program at Eastern New Mexico University to staff our first field school in the early summer of 1999.

That first dig was in a large room in a sprawling pueblo ruin called the Victorio Site. Situated on some forty acres of tableland above Alamosa Creek, Victorio contained an estimated 450 rooms in fifty room blocks of varying sizes. In two weeks’ time, the six-person crew dug through the collapsed roof and down to the packed earthen floor of the room we’d chosen to dig. Its muddied stone walls were uncovered, a fire pit and grinding pad emerged, a two-cell grain storage bin was preserved, and many artifacts (dating mostly from the 1200s CE) were found and bagged by scrapping and sifting. Photographs were taken as we went down level by level in the meter-square units. This pattern at Feature 1, Victorio Site, became our modus operandi in subsequent field schools.

Trudy became the cook and food organizer for the field schools, feeding twenty to twenty-five people per night over a ten-day stretch three times per year. The volunteers ranged from 17 to 87 years of age. They came from across the country and overseas. Most were recruited through Earthwatch Institute, based in Boston.

Ranch manager Randy Furr and I were the tent raisers and platform menders for the village we erected in the grove of trees around the Maytag Cabin, the field school headquarters. Randy kept the electrical and water systems working; I joined the volunteers when they went to the excavation site most mornings. I also organized a public program of guest speakers for the field schools and the Monticello community. They addressed their audiences in the nineteenth-century Catholic mission church in Monticello, and usually up at the ranch as well.

Archaeological excavation, I learned, is demanding but gratifying work. Hot, gritty, and focused, but the reward comes in finding pieces of ancient pottery, stone tools, bones and the like in nearly every bucketful of screened room fill. Mornings were for digging. Afternoons, after lunch, were for lab work in the shade—cleaning, washing, sorting and bagging artifacts—and the lectures, discussions, analysis, and demonstrations which usually followed.

Our research design called for excavation at four sites: Victorio, Pinnacle Ruin, and the Kelly Canyon and Montoya Sites. Each of the others is considerably smaller than Victorio, but significant enough to warrant digging during two or more field schools. We also undertook walking surveys of the numerous other pueblo sites that dotted the table land in the canyon and officially recorded them, and identified, mapped, and collected at the nearby Apache sites we were able to locate.

To capture some of the more recent history of the canyon, the times after Europeans arrived, settled, and interacted with native peoples in the Alamosa watershed, we undertook an oral history project that consisted of recorded interviews with descendants of nineteenth- and twentieth-century occupants of Cañada Alamosa: Warm Springs Apaches, Hispanics, and Anglos.

Following that first excavation at the Victorio Site in 1999, we welcomed two field schools every June and one in October annually until our concluding session in June 2011. Pinnacle Ruin and the Kelly Canyon and Montoya Sites were each investigated during multiple sessions and each year’s findings were written up in a preliminary report that contained photographs, charts, and other illustrations of the year’s work along with an interpretive text. (Pinnacle Ruin was the special province of Steve Lekson of the University of Colorado. He and groups of CU students worked that rich site for six seasons.)

The last of our 20 oral history interviews took place in 2011; transcriptions of all were made, edited, and completed by the following year; and a set of them was delivered to the New Mexico State Archives in Santa Fe in 2013.

To give the project longevity, we created a website. Another major culminating event was the exhibition “The Cañada Alamosa Project: 4000 Years of Agricultural History,” which was on display at the New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum in Las Cruces from February through June 2014 (go here for a virtual tour). On the website, you can also find videos with a glimpse of field school life as it happened.

When we left New Hampshire for the outback of New Mexico in January 1999, I thought one of the biggest challenges I would face in my “semi-retirement” would be coping with the absence of the webs of human relationships from work, within our family, and in our local community; and the stimulation, learning, satisfaction, and creative moments these webs can bring. In thinking back on those sixteen years (we sold the ranch and moved to Santa Fe in the fall of 2014) we lived, worked, and learned along Alamosa Creek, I see now how a whole new web of relationships—friendships, partnerships, neighbors, intellectual ties—grew out of our project and enriched our lives.

Semi-retirement, for me, has proven to be an adventure full of discoveries, one that greatly broadened my awareness of self, physical surroundings, and history, both natural and human. My conception of American history was completely changed by my experience of digging into the past in southern New Mexico. I used to think of the settlement of Jamestown as being “early American history.” The four-thousand-year-old charred corn cob we unearthed at the Montoya Site in 2011, our last dig, along with all the other cultural materials we brought to light over thirteen years of excavation, have given me a whole new take on how very old, deeply layered, and culturally intertwined American history really is.

In May of 2016, I drove from Santa Fe down to Albuquerque to meet Karl Laumbach and his son, Kris, at the University of New Mexico’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology. I joined them in delivering to the Maxwell’s Hibben Center staff a van full of boxes containing most of the collections of the Cañada Alamosa Project. This bringing together and depositing in one place our work in the field, the lab, and in print constitutes the harvest of the venture we began back in 1999. We’ve been able to add major new elements to the trove of primary sources and to challenge several of the accepted interpretations already available from which the remarkable history of the American Southwest has been told. Semi-retirement, for me, has proven deeply satisfying.